Eight years have passed but Amparo Andújar Maldonado does not forget. She lost her first child while she was approaching the fifth month of her pregnancy.

Nor does she erases from her mind giving birth to a disfigured fetus, with cranial malformation, something incomprehensible for a healthy 27 year old woman, counting with quality prenatal care.

Gary Gutiérrez

Pedestrian bridge in Santa Bárbara de Samaná where many go to watch Humpback whales.

But Amparo was not alone. From 2005 to 2008, the rate of miscarriages and premature births rose suddenly in the Encantado neighborhood of Arroyo Barril, a working-class rural and coastal town, north of the Dominican Republic. An area rich in natural treasures such as the Bay of Samaná, global sanctuary for humpback whales.

Amaparo’s friend, Rosa María Andújar, also fell into statistics. She gave birth to a child with exposed intestines and six fingers and toes. The newborn died not far from birth, in June 2008.

Months later, another neighbor, Maribel Mercedes, gave birth to Siamese twins that also died in a short time. Five babies were born with omphalocele or exposed intestines, between August and November of that year, in neighboring districts Los Róbalos, La Pascuala and Gri-Gri. Only one of them survived.

When asking Andújar Maldonado what explanation sanitary authorities gave about her case and about the unusual repetition of similar cases in the region, her answer was simple: “None”.

Amaparo’s house is located less than half a kilometer from the dock and during the pregnancy she would regularly go to the beach “to get some air”.

“I think it was because of that”, she added.

By saying “that” she refers to the tons of coal ash that stayed abandoned in the Juan Pablo Duarte dock at Arroyo Barril for almost four years. Mounds of more than 27 thousand tons of the grayish residue that arrived at the pier from the AES carbon plant in Guayama, Puerto Rico, and that they were unloaded, steps from the coast, in the open and without a management plan, on October 2003.

Since the year 2002, the company AES has generated between 400 and 1,600 daily tons of this waste while producing the electricity it sells to the Puerto Rico Power Authority (PREPA) and, by a contract with the government, it bound itself to export the waste for which it did not find commercial use.

Neighbors and ex-employees from the Dominican port acknowledged that an undetermined amount of that ash material, identified by locals as “rockash”, ended up in the sea. When this happened, it was common to encounter dead fish banks in the coast.

“The water that came down would kill the fish”, Miguel Ángel Paredes Jiménez assured. He was the security chief at the Arroyo Barril port in the year 2004.

Part of the ashes, they assured, were also dragged for months by the coastal breeze to nearby communities, agricultural land and to the mountains of the town.

A sample analysis conducted by the Institute of Chemistry at the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo released in April 2004, certified that the waste brought from Puerto Rico was loaded with heavy metals. Specifically, they identified levels of beryllium, vanadium and cadmium “exceeding the levels of international standards”. Also high concentrations of arsenic.

The Technical University of Delft, in the Netherlands, describes beryllium as one of the “most toxic known” elements in the world since “it can be very harmful when inhaled by humans” and may “increase the chances of developing cancer and DNA damage.” In addition, it can accumulate in the air, soil and water.

By 2005, about 1,600 families lived in the village of Arroyo Barril and nearly 40 percent of them lacked aqueducts so they went to nearby rivers and springs for drinking water and basic needs. Today a minority continues the same practice.

The alert caused by the rise in miscarriages in those years was such that regional leaders of the Ministry of Health adopted an extraordinary measure.

“We asked the women of age to prevent pregnancy for a while, because there were many abortions,” recalled Dr. Rosa Domingo Maleno, who since 2004 occupies the position of Provincial Director of Health in Samaná region, to which Arroyo Barril is assigned.

Domingo Maleno could not provide figures of registered miscarriages during those years.

“The land is contaminated”

Gary Gutiérrez

Concepción García Bueno, resident of Arroyo Barril.

Facing one of the gorges of the Encantado neighborhood, and passing the dirt road leading to Amparo’s home, lives Concepción García Bueno, a strong farmer who can no longer do his job.

Surrounded by neighbors, he explained that since the arrival of rockash in the Arroyo Barril dock, fruit trees are no longer productive and assured that the plantains, orange, grapefruit, pigeon peas and avocado no longer grow in his orchard.

“Here in our territory you can ask around if anyone can bring you an orange or a grapefruit. It doesn’t exist; there are none. And that’s because of this epidemic,” he said referring to the mountains of ash.

“The leaves have dried and fallen. They are disappearing. The land here in our territory, doesn’t produce them. The soil is affected, it’s polluted,” he said.

“Had you noticed a similar problem before?” he was questioned.

“Never, never. (We had not had) any epidemics. Thereafter, it has been a disaster,” he said. “But we are already contaminated and there is no way out of this evil”.

Since the arrival of rockash, he added, the soil that for decades gave food to his family and neighbors was transformed. Now they are forced to buy legumes, fruits and vegetables from farmers or sellers from other localities.

How could the fields of Arroyo Barril be contaminated with ash waste if the mountains of waste were in the dock? García Bueno gave a quick and clear answer: through the sea breeze.

“My mother’s house is half a kilometer away from where they deposited that mineral and they had to be cleaning all the time. It was like a powder, the one they use for babies,” he said.

But the propagation of the ashes had other underpinning.

As described by Jose Eligio García Jiménez, a religious leader and veteran tourist carrier of the Province of Samaná, a few months after the arrival of rockash, hundreds of people came to the dock Arroyo Barril to load cargo of the coal ash to their homes, relying on public notices of the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, as well as assertions from port operators.

Both sources said that the material could be used for construction and flooring.

That’s why, García Jiménez said it was not unusual to see carpets of ashes at the entrances and courtyards of homes even in distant locations from the port as the municipalities of Sánchez and El Limón, located more than 20 kilometers from the port.

Gary Gutiérrez

José Eligio García Jiménez, tourism chauffeur on the Samaná Province.

“Many people came to load (the ashes) in trucks to throw in front of their yard because it was something that looked nice, like a white sand, something pretty. And that was the curse,” he said.

“Then all those people came in sick. All of them”, he told. Among other symptoms, the driver said that “first, the children and then, adults” began to manifest bone pain, fever, swelling in the body and itching or hives. Unlike diseases such as dengue fever, common in tropical areas, the symptoms persisted and lasted for months.

“We were saying ‘but why does the whole family, in one house, has all these symptoms of illness and nobody knew what it was? Nobody. And it was ‘that’ killing us. The rockash”.

María Andújar Mercedes, another neighbor of the dock, added that families who used rockash as construction material also used it to cover the floors of their kitchens because it is common in the area to have dirt floor kitchens separated from the houses.

Even the coconuts were affected

Among those who raised the voice of alarm figured Eugenio Andújar Maldonado, the current president of the Neighbors United for Peace of Arroyo Barril.

Standing in front of the Nagua Samaná highway, the main artery of the place, Andújar looked at coconut palms and pointed to them as a first indicator that something strange was happening.

“Many coconut trees were damaged, that is, they dried,” he recalled.

In Arroyo Barril, as in the rest of the Province of Samaná, economic activity is centered on tourism, fishing and agriculture. In the latter, the main agricultural product was the coconut as certified by the Ministry of Agriculture of Samaná.

The community leader also warned that since the coal ash spill local production of yams, cassava, plantain, grapefruit and avocado inexplicably dwindled “up to 70 percent”. Drought is a recent phenomenon and other sources of pollution that can damage soil do not exist near Arroyo Barril.

As an example, he stated that the nearest landfill located is 15 kilometers from the town; the processing plant of gold Cotuí is 200 kilometers away; and the nearest cement plant is situated in the Province of Santiago, “260 kilometers from here”.

In his own flesh

Dr. Eduardo Ortiz Mejías, then assigned to the Primary Care Unit of Arroyo Barril, also remembers precisely these incidents some of which caught the public attention.

In fact, the doctor not only certified that the frequency of miscarriages and births of children with deformities was atypical in Arroyo Barril between 2005 and 2008 but narrated how he was surprised with the news of the loss of his firstborn in January 26, 2006.

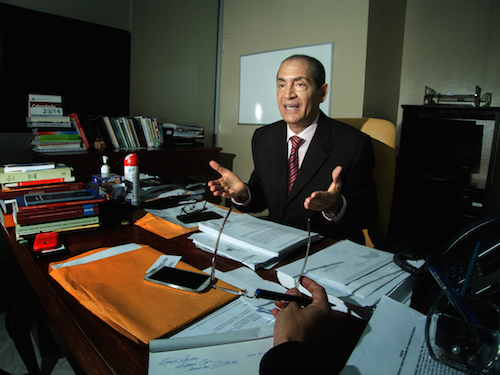

Gary Gutiérrez

Dr. Eduardo Ortiz Mejías

“That was the first child. She became pregnant in December and in January 26 even though we took all the preventive measures she lost the baby,” he said. His wife was eight weeks into gestation.

The doctor, now active in the Leopoldo Pou Hospital at Samaná Province, explained that this was the first and only time in their family histories that such a tragedy occurred.

He confessed that accepting and assimilating it was difficult.

As a man of science, it has been challenging to find an explanation to what happened. But he recognizes that something was happening in Arroyo Barril and moved away from there in 2005.

“I come from a contaminated town, completely polluted, called San Pedro de Macoris, a province where there are many free trade zones and there is a very broad environmental impact. But when I am there, in San Pedro, I don’t see the diseases that I’ve seen there,” he said.

Among those observed in Arroyo Barril he mentioned rashes, miscarriages, repeated abortions, premature births, malformations “and what was seen only in textbooks: Siamese” twins.

“We also had children who were born without the two extremities. This condition is called Amelia,” he added.

The problem, however, is complicated because in his opinion the incidence of these cases persists.

“We’ve had the bad luck that we do not know anymore when the pregnant women (in Arroyo Barril) will give birth. What is the cause? We do not know,” he said.

“They just say ‘it is God’s destiny’ ‘it had to happen’, but if a thorough investigation is done I think we can come down to the real reasons,” the doctor continued .

The study would indicate whether Arroyo Barril has been contaminated by toxics and the origin. In addition, it would shed light on the possible presence of heavy metals in the blood of residents and in water and agricultural lands of the municipality.

This request is supported by Dr. Nabal Ireon Báez Beevers, Area Manager of Health at the Province of Samaná, who said that the landing of rockash never should have happened, let alone in such an area which is close to populated communities. “That is a toxic,” he said.

Exposure to toxic chemicals, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics has said, is a problem that threatens human reproduction “disproportionately among the poor.”

For example, in 2015 it concluded that “miscarriages, stillbirths, impaired fetal growth, congenital malformations, alteration or reduction of neural development and cognitive function” are some of the effects on reproductive health related to exposure to chemicals and air pollutants products.

The group representing gynecologists and obstetricians from 125 countries also ruled that negligible exposures to heavy metals during the prenatal period may interfere with the development of a child “triggering adverse health consequences that may manifest through the life expectancy”.

A thorough investigation on this topic could materialize soon in Arroyo Barril if the claims of a prolonged legal battle against AES Puerto Rico and its parent company, AES Corporation, are supported by the court, said Báez Beevers.

The civil lawsuit filed by lawyers representing about twenty residents of Samaná was presented in 2009 before the Superior Court of Delaware. The case is alive and proposes that the 27 thousand tons of coal ash discharged in Arroyo Barril were toxic and sickened people in the area.

The Center for Investigative Journalism learned that last February 6 AES Corporation attorneys met at a hotel in Santo Domingo with the plaintiffs and their lawyers, and presented an economic proposal to end the trial in an attempt to settle the case. This happened after the Center conducted on site interviews related to this investigation.

The plaintiffs rejected the offer of AES so the case under the consideration of the presiding judge of the Superior Court of Delaware, Jan R. Jurden, continues.

Manuel Mata, chief executive of AES Puerto Rico, did not agree to be interviewed by the Center for Investigative Journalism.

The story repeats at the border

Another witness to what happened with the ashes is the lawyer and current Deputy Attorney General of the Attorney General of the Dominican Republic, Ramón Madera Arias.

Gary Gutiérrez

In 2004 Ramón Madera Arias was then General Prosecutor for Environmental Defense in Montecristi, Dominican Republic.

But his awareness of rockash didn’t happen in Samaná. It was in the province of Montecristi, located on the northwestern tip of the Dominican Republic, at the border with Haiti, where the company Trans-Dominican Development unloaded 30,000 tons of coal ash in 2003 that were discarded by AES in Guayama, Puerto Rico.

As stated in the official permit issued by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources of the country in 2003, the mountains of ash material brought to the port of Manzanillo would be used to expand its cargo area.

However, Madera Arias, then Attorney General for Environmental Defense, warned that the tons of compacted ashes had been discharged less than 100 meters from the beach and the adjacent wetland was disappearing.

“Some mangroves were there. That was a very green area and it started to dry, to deteriorate, and to damage,” he described. “And a dust polluting the air was flying around.”

In a previous conversation, the journalist Arsenio Cruz from the El Caribe daily newspaper had notified Madera Arias that a coal ash cloud had flooded the town of Manzanillo and that “everyone is choking; they can’t take it.”

“People couldn’t lie down in their homes, because even the blankets, the bed, was been filled with that dust. It had penetrated (the homes), it had flown with the breeze,” he recalled.

Reacting to the allegations, Madera Arias rushed to the scene, confirmed the facts and presented a ruling which ordered the immediate cease of activities associated with ash handling. He also banned the import of that waste as another shipment was on its way.

This, however, did not stop the wave of bad health which affected much of the 10,000 residents of the municipality, now known under the name of Pepillo Salcedo.

“In Manzanillo, more than 90 percent of the people had welts, itching, skin diseases,” he said. “If you talked to 100 people in the town, 80 or 90 would have the symptoms… but the same happened in Carbonera, which is two or three kilometers,” he said.

The explanation offered by Madera Arias is that Carbonera receives the sea breeze directly from Manzanillo.

Another tragedy, the official regretted, was that “10 to 12 people who were healthy and young” were diagnosed with cancer. “Skin cancer and lung cancer.” The victims were all known to Madera Arias given that he is a native of the province.

In the second part of the series, we inquire about what happens in Puerto Rico, where it the government just legalized this toxic ash disposal.

Toxic Ash: A Caribbean time bomb is the result of collaboration between the Center for Investigative Journalism and La Perla del Sur newspaper, through a special grant of environmental journalism awarded by “Para la Naturaleza”. See the complete series with its graphics and interactives in periodismoinvestigativo.com