The most recent version of Puerto Rico’s fiscal plan for its central government would chart the future of the country, giving some degree of certainty to citizens, businesses and investors to bet on the island’s dismal economy. Yet it is built on economic projections totally incompatible with the historical experience of places that have been destroyed by hurricanes the world over.

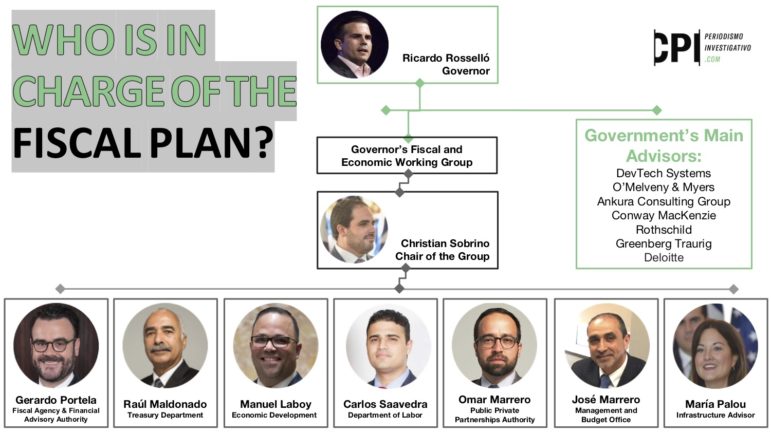

The plan also clashes with what has been Puerto Rico’s economic trajectory. In the past 30 years, the economy has never reached annual growth such as that estimated for fiscal year 2019 by the financial team of Governor Ricardo Rosselló Nevares. The group is led by Christian Sobrino, governor’s representative before the Fiscal Control Board (FCB), chief economic adviser to the governor, president of the Government Development Bank and chairman of the Financial Advisory & Fiscal Agency Authority (AAFAF by its Spanish acronym); and Gerardo Portela, executive director of AAFAF and by virtue of his position, member of the boards of directors of all public corporations. Neither of them has studies or experience in public finances or in government.

Over the past two years and a half, Puerto Rico has seen nine different versions of long-term fiscal and economic growth plans. The first three were prepared by the administration of former Gov. Alejandro García Padilla, while the remaining six by Gov. Rosselló Nevares. Although the exact cost of this exercise is still unknown, more than $90 million is currently awarded in contracts to the advisors and lawyers that assist the government in producing these plans, a search conducted by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CIJ) found. AAFAF didn’t answer a request for information over how much money Puerto Rico spends in consultants that work with the commonwealth’s fiscal plans and how much is budgeted for the effort.

Despite the hefty investment of time and money, all the plans generally include similar revenue and expense measures based on ever-changing economic growth projections that show the high level of uncertainty in the process. Take for instance the projections made by the FCB in December 2016, when a -17.10% fall in gross national product (GNP) was expected for fiscal year 2018, even before Hurricane María. Shortly after that, the projection was revised to -2.8%. After María’s passage, it stands at -11%.

None of the plans include sufficient technical and methodological details on how they arrive at their projections. They have all faced broad opposition from different sectors, including the major holders of Puerto Rico’s public debt.

In a nutshell, all plans share a critical problem: None can really reflect what the future of Puerto Rico will be. As the U.S. unincorporated territory continues to push through bankruptcy under Title III of PROMESA, it will be the Federal Court and the debt-restructuring process which, at the end of the day, decide how much money will be available for the government operation and how much will go to pay creditors. This would break with much of what has been proposed nowadays in all the fiscal plans.

The CIJ reviewed the different versions of the central government’s fiscal plan, as well as several analyses and independent studies on the economic impact of hurricanes around the world and how they relate to the most recent projections made by the FCB and the Puerto Rico government.

Among these, one of the most striking is “The Causal Effect of Environmental Catastrophe on Long-Run Economic Growth: Evidence From 6,700 Cyclones,” a study made by economists Solomon M. Hsiang and Amir S. Jina for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization based in Cambridge, Mass. The International Monetary Fund, the University of Heidelberg in Germany and the University of Arizona are replicating the investigation, which looks back at all the cyclones that have made landfall between 1950 and 2008.

The Puerto Rico government and the FCB are well-acquainted with this study. In November, Jina participated of a public listening session held by the FCB to discuss the new fiscal plans after María. During his presentation, Jina said that following a hurricane landfall, most jurisdictions show a negative trend in economic growth that runs for at least 15 years. The study also finds that the majority of the affected economies fail to recover the level they had prior to the hurricane until at least 20 years later, with some cases taking up to 30 years.

The average downward economic trend shown in the study holds true regardless of the infused recovery funds, the type of the public policies implemented, the size of the country, or whether it is rich or poor. Economies that were generally growing before the hurricane could stay in positive territory but at a slower pace.

Amir S. Jina

“There are perhaps very strong assumptions which imply Puerto Rico gets back to positive growth, but given our general research and what we’ve found looking at every hurricane that has happened so far, we see that given that Puerto Rico should have been on a very flat growth trajectory, it would imply that it would get pulled to negative,” Jina told CIJ. The latest projections from the Puerto Rico government state that the economy will grow every year with the exception of the current one, with increases in gross national product (GNP) ranging from 8.4% in fiscal 2019 to 2.1% in fiscal 2023.

The distinct case study has caught the attention of Jina and many of his colleagues, who have continued to run projections on Puerto Rico’s economy. After all, very few places, if any, have shared the U.S. territory’s “extremely unique” political status, downward economic spiral and high indebtedness prior to a hurricane landfall, which makes it even harder to assess the Puerto Rico case.

Although Jina warned it is highly uncertain to project how the island’s economy would behave in the first two to three years after María, their long-term estimates coincide with the average negative trend in economic growth found in the NBER study. Their projections so far suggest a fall of roughly 21% in gross domestic product (GDP) levels over the next 15 years, vis a vis scenario where Hurricane María had not made landfall the way it did, he added.

“Policymakers and political scientists would have opinions, but as far as the data are concerned from the history of every land-falling hurricane, there would be this large decline predicted for Puerto Rico over the next couple of decades unless some dramatic change takes place,” Jina noted.

The most recent version of the fiscal plan projects an increase in real GNP of 19.4 percentage points between now and the fiscal year ending June 30, 2019. It is a growth projection without parallel in the world economy, and even more so when compared with Puerto Rico’s history, according to several economists interviewed by CIJ.

To achieve the projected growth, the Rosselló administration doubles down on the billions of dollars that Puerto Rico would receive from the federal government to reconstruct the island’s infrastructure after María. At the moment, the latter figure surpasses $50 billion over the next five years. It includes more than $16 billion that was approved by Congress earlier this month and of which $4.8 billion is specifically intended to cover the operational deficit of Mi Salud, the local public health plan. To a lesser degree, Gov. Rosselló points to a host of “structural reforms” that along with “savings” in government spending, would “balance the budget and stop the deterioration of the economy.”

A key driver to project economic performance, economists interviewed by the CIJ agreed that it is difficult to determine how much of these reconstruction funds would stay on the island economy. Some noted, for instance, that most of the large contracts have been awarded to U.S. mainland companies, which would cut down on the positive impact these monies could have on the local economy.

“A lot of the rebuilding funds and firms coming in are U.S. firms so salaries are going back to the mainland as opposed to Puerto Ricans. What is the percent that remains in Puerto Rico? That’s a big question and very difficult to answer,” Jina said.

Economists such as Dr. Antonio Fernós Sagebien, a professor at the Inter American University, and Martín Guzmán, a professor at Columbia University, have openly questioned the lack of transparency in the methodology used by both the government and the FCB, as well as the economic projections included among the different versions of the fiscal plan.

Along with Joseph Stiglitz, an Economics Nobel laureate, and Pablo Gluzmann, an economist and director of the Labor Database for Latin America, Guzmán deep-dived into the projections of the fiscal plan certified in March 2017, as part of a debt sustainability analysis of Puerto Rico commissioned by Espacios Abiertos, a nonprofit organization. In September, Guzmán made available, at no cost, the methodology used by the group through a letter sent to Natalie Jaresko, executive director of the FCB. He has yet to receive an answer.

“Regarding the analysis of the Fiscal Plan certified in March 2017, the conclusion is unequivocal: it is a plan based on unrealistic and inadequate assumptions that lead to an underestimation of the negative consequences that its implementation would have for Puerto Rican society,” said Guzmán during a visit to Puerto Rico last month. He anticipated that the successive version of the plan would have the same problems if it were based on the same precepts. Once the FCB recertifies a fiscal plan for Puerto Rico, Guzmán will run the debt sustainability analysis again, he told CIJ.

For his part, Fernós Sagebien said the two versions of the plan unveiled by the government following María “are just as bad” as the previous versions, from a methodological standpoint. He noted how the consumer price index is used as deflator and how it fails to factor the reality that a large amount of federal rebuilding funds are often used to hire U.S. mainland companies, as Jina pointed out. He also points out to the incompatibility between GNP growth forecasts and some of the data contained in the plan, namely the negative impact that migration will have and the reduction in tax rates proposed for both individuals and corporations under a new tax reform.

“That does not make sense. They have to tell me how they anticipate these increases in revenues. If there are fewer people, and fewer people working, there will be less [revenues from] taxes,” Fernós Sagebien said. He added that the entire equation fails to contemplate the impact that the future of the Electric Power Authority will have on public finances and the economy.

By fiscal 2023, even though the latest fiscal plan says almost 20% of Puerto Rico’s 3 million-plus population would leave the island—and with them, part of the government’s tax base—the Rosselló administration continues to bet that revenues will be “3% higher than pre-storm levels.”

Similarly, economist Francisco Catalá stressed that Puerto Rico has already experienced 12 years of economic contraction and the most recent version of the fiscal plan makes aggressive GNP growth projections.

“There has been growth of more than 7% on very few occasions in Puerto Rico. In some years of the 1950s and 1960s. Of course, it is assuming a large influx of federal funds,” said Catalá. He noted, for instance, that plan’s projected increase in tax collections from corporations and individuals runs counter to migration estimates, business shutdowns and tax rate cuts proposed in the tax reform.

Matt Fabian, financial analyst and partner at Municipal Market Analytics, believes Puerto Rico needs to be more self-sustainable and not bet it will receive more funds from Uncle Sam in the future. “There’s a line in the fiscal plan that talks about using the federal government as a partner or relying on them, and that’s madness. It’s madness to rely on the federal government and on ‘this’ federal government for incremental aid over the next five, ten years. They need to think sustainably about what they can do on their own,” Fabian commented.

Photo by Brando Cruz | Center for Investigative Journalism

Gerardo Portela in the first listening session held by the FCB after Hurricane María

When asked by CIJ on how the government came up with its projections, AAFAF Director Portela Franco said the macroeconomic projections are “holistic” and were a “great job” of DevTech, the government’s economic advisers, and FCB consultants, using the input of the listening sessions held in November and early December. The government has refused to publicly disclose the methodology and model used by DevTech arguing it is proprietary material.

Nevertheless, he acknowledged fiscal plans have been approved “with little or limited financial information,”

During the interview, Portela was specifically asked if they took into consideration the study and presentation of Hsiang and Jina, but couldn’t remember.

How were social priorities determined in the fiscal plan after Hurricane María?

“Social priorities have always been to protect public employees, protect pensions. And that has always been the case among all the plans; that has never changed,” Portela answered. Yet, since the fiscal plan presented by Gov. Rosselló Nevares on Feb. 28, 2017, reduction in government pensions and fringe benefits to public employees have been contemplated to some degree.

In the case of Sobrino, he admitted that the previous fiscal plan contemplated a cut in pensions, although less than what the FCB required.

“In this plan, we cannot [reduce pensions]. Given the demographic situation of Puerto Rico, we understand that this would be too strong an impact on a particular sector of the population,” said the governor’s representative before the FCB. Sobrino further acknowledged there are elements in the new plan that depend on uncertain scenarios, but he defended most of the assumptions as “very well-reasoned.”

“What we are trying to avoid is falling into the spiral that leads to unsustainability as a jurisdiction. We want to make the reforms and decisions that have to be made so that Puerto Rico is sustainable and has positive economic growth, whatever it may be, in the long term. That complies with PROMESA,” he added.

Photo by Brandon Cruz | Center for Investigative Journalism

Christian Sobrino in the first listening session held by the FCB after Hurricane María

The 33-year-old lawyer, who chairs the Governor’s Fiscal & Economic Working Group—which is tasked with implementing the fiscal plan—holds a juris doctor from the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) and a bachelor’s degree in English from Boston College. Prior to his current positions in government, Sobrino worked as ethics & compliance director for AbbVie in Puerto Rico, as well as in the local law firms of Pietrantoni Méndez & Álvarez, and O’Neill & Borges. Before joining the government, Portela, 40, worked as an investment banker at Santander Securities. He has a master’s degree in business administration from University of Virginia and a bachelor’s degree in finance from the UPR.

“I’m convinced that [Gov.] Ricardo Rosselló has the best intentions, but he is going through the worst moment of the country’s history and is surrounded by people who do not have enough experience, nor the training, to workout this situation with the seriousness it deserves,” Fernós Sagebien told CIJ, after evaluating the latest version of the plan.

The governor’s office has yet to respond to a CIJ request for interview made In January.

Measures with lagging results

Most expense-reduction and economic-growth measures in the latest Fiscal Plan were part of older plans, some of which have been promoted by previous government administrations with little or no success. These include agency consolidations, transferring public employees, early retirement windows, subsidy reductions, curbing tax evasion, health reform that reduces costs and changes to the tax code.

The last two versions of the plan also call for establishing an earned income tax credit (EITC), to encourage labor participation on the island, one of the lowest in the world at roughly 40%.

According to the Fiscal Plan, among the measures that stand to generate the greatest savings are the so-called “New Government Model,” the administration’s initiative to reduce the number of agencies by more than a half, while vowing there will be no layoffs of public employees; and the “New Health Reform,” which really depends on the result of a request for proposal process launched this month.

Among those that will boost revenues, is improving government’s efficiency in collecting taxes, along with a revision to the alternative minimum tax and limiting tax credits and incentives. The document fails to go into detail nor provides the breakdown of revenues that the FCB requested.

In late January, Sobrino told CIJ there is a general consensus with the FCB on the macroeconomic projections. He believed, however, “there is going to be more debate soon, and it has to do with criteria, in the areas of implementation of certain measures, the forecasts of revenues in some line [items].”

The FCB has yet to respond to CIJ’s requests for interview with Executive Director Jaresko and FCB Chairman José Carrión, both of which were made since last November.

Photo by Brandon Cruz | Center for Investigative Journalism

From left to right: José Carrión, Natalie Jaresko. Ana Matosantos and David Skeel.

As of this writing, and following meetings last week between the governor and members of the FCB in New York, the fiscal board pushed the date on which it expects to certify a new Fiscal Plan, from Feb. 23 to March 30. After submitting a new draft of the plan on Feb. 12, it is still uncertain whether the FCB will ask the Rosselló Nevares administration to submit yet another revision of the document.

A savings pillar of the Fiscal Plan and one of the bones of contention between the FCB and the government is the reduction of public payroll. The Rosselló administration flatly denies that the Plan—which includes a reduction of 8,000 government jobs by fiscal 2023 across 105 agencies—includes layoffs or furloughs. Instead, it argues that the $319 million in projected savings for fiscal 2023 included in this line will be achieved with two of the administration’s chief programs: Empleador Único, Spanish for converting the central government into a single employer; and the Voluntary Transition Program. A third component, attrition, would also help reach the savings target.

The Empleador Único initiative calls for the transfer of employees between agencies according to human resource needs, while featuring a strong retraining component so that all public servants can be in a position to “transform” and learn the skills that are needed in the government. The Voluntary Transition Program provides an economic incentive to employees who wish to leave public service and “transition” to the private sector.

As of Feb. 6, some 2,250 employees had solicit to participate of the Voluntary Transition Program, which began Nov. 15. A total of 1,185 applications have been granted, while 18 rejected. AAFAF failed to provide the status of the remaining 1,065. “Once the Voluntary Transition Program ends in March 2018, an accurate number of what the savings will be for fiscal year 2019 can be offered,” the government’s fiscal agency said in writing.

In the case of Empleador Único, which became Gov. Rosselló’s flagship program and his eighth law signed a year ago, only 100 employees in the local Treasury Department have been transferred using the new model. While the administration trumpets the program as one of the main mechanisms to avoid laying off public employees while drastically reducing the number of agencies, CIJ discovered that the required retraining program has yet to be implemented. All in all, the initiative continues mostly on paper.

By the end of this month, the Rosselló Nevares administration expects to have ready “mobility plans,” which are key to begin the retooling of the government structure, according to Carlos Saavedra, Puerto Rico’s Labor secretary. The “mobility plans” are folders with information of every public employee, including their skills and preparation, as well as HR needs of each agency.

“Once we have those mobility plans that the [Empleador Único] law requires, we can go into the specific needs of each agency and discuss how they will be tackled,” Saavedra said. The execution of the government-as-a-single-employer program will begin “during this year,” he added. The Labor secretary admitted he still doesn’t have the estimated number of employees that could be impacted by the program because “the needs” of personnel across the government are still unknown.

Although both initiatives are two of the most significant cost-reduction measures in the fiscal plan, both AAFAF and Labor failed to provide details about saving estimates specific to both programs. This puts into question the projections of savings contained in the new fiscal plan and that remain basically encompassed along with other measures.

Two government sources, moreover, said that even after María, the FCB remains steadfast in its urge to further reduce government headcount in a more aggressive way.

In the meantime, public employees continue to be swarmed with uncertainty.

“Nothing has been done. We have not received much information,” said a government employee who requested anonymity. “There are employees who have asked for information but there is very little. There are many of us who do not know what will really happen,” the source added.

Since the delivery of the first proposed fiscal plan, the FCB has raised flags over the Puerto Rico government’s efforts in reducing its operational spending. As it stated in a Feb. 5 letter to Gov. Rosselló Nevares, the board understands that the latest Fiscal Plan overestimates the economic impact of various measures aimed at reducing government payroll costs. The FCB further states the proposed initiatives won’t lead to a government “with the right size,” when considering the population decline Puerto Rico has been suffering in the past decade and which is expected to worsen in the next few years. The board stresses that Puerto Rico needs to include pension reductions, along with more cuts in personnel and services costs, to achieve a smaller government, while also urging for more detailed information on some of the plan’s components.

The most recent Fiscal Plan of Rosselló Nevares, unveiled Feb. 12, revised down some of the estimated savings of government right-sizing measures, but leaves out pension cuts nor provides all the additional information requested by the FCB. The newest plan proposes $200 million more in savings during the next fiscal year, but instead of cutting expenses, the Rosselló Nevares administration will “adjust” the alternative minimum tax rate for individuals and companies, and “broadly reduce” tax credits and incentives granted by the government.

In the Department of Education, the reduction in the size of Puerto Rico’s public instruction system—together with a decrease of 34,600 students just in the next school year—will generate some savings in the agency’s budget, including payroll. The most recent fiscal plan anticipates savings of $71.1 million during the next fiscal year, and $305.3 million by fiscal 2023. However, the “educational reform” of Gov. Rosselló Nevares, which proposes educational vouchers and charter schools, already faces fierce opposition from teachers and some members of the governor’s own party, raising flags as to the administration’s possibilities to implement the proposed reform as envisioned and, thus, achieve the projected savings.

In the case of the Department of Correction, the plan projects $45.8 million less in spending in fiscal 2019 and $136 million by fiscal 2023, while at the Department of Health, the expectation is $51.4 million and $91.9 million, respectively.

All at once?

The bulk of the savings under Gov. Rosselló’s “New Government” model would come through what the fiscal plan calls the “transformation of the rest of the agencies,” through which some 108 government agencies are to be consolidated into a maximum of 35. Through attrition, Empleador Único, the Voluntary Retirement Program and a reduction in health benefits, the government projects savings of $121.8 million in fiscal 2019, and up to $379.3 million by fiscal 2023.

The consolidation of these agencies would allegedly entail a reduction in the number of employees, from 48,100 to 40,500, and total savings of $619.8 million by June 30, 2023.

So far, the Rosselló administration’s experience in restructuring the government apparatus reflects the complexity in executing the measures as proposed. Examples of this are the five “reorganization plans” that the Government has presented so far for the departments of Economic Development & Commerce (DDEC by its Spanish initials) and Labor, the Bosque Modelo (Model Forest), the Public Education Board and the newly proposed Public Service Regulatory Board (JRSP by its Spanish initials). Three of these plans —DDEC, the Public Education Board and the JRSP—were withdrawn amid different setbacks.

Although Gov. Rossello’s first fiscal plan in February of last year included the consolidation of several services and agencies during the current fiscal year, including Economic Development, Family, Education and Public Safety. To date, only the consolidation of seven agencies into the new Public Safety Department (DSP by its Spanish initials) has been achieved. Although the law creating the DSP was signed in April 2017, the level of savings achieved under this restructuring still remains unknown.

The real plan

Regardless of what the FCB and the commonwealth government establish in the new fiscal plan, it will be another “plan” which will greatly dictate Puerto Rico’s fiscal future.

A characteristic element of bankruptcy, the “plan of adjustment” under Title III of PROMESA will establish how much debt the Government will have to repay, when it will do it, to whom it will pay and the order of preference among the different creditor groups.

The board holds the exclusive power to present this “plan of adjustment” on behalf any government entity that goes into Title III, while the federal court would have the final word on the approval of the document. It also involves a voting process by different classes of creditors.

Artwork by Elizabeth Williams

Laura Taylor Swain, the judge presiding over Title III case.

Amid the absence of a “plan of adjustment” and legal fight over different revenue sources of the government of Puerto Rico, the Rosselló Nevares administration categorizes as “agnostic” or “neutral” its fiscal plan regarding the treatment given to the commonwealth’s creditors. Any decision that affects the amount of resources available to the government—as the plan of adjustment would do—would significantly change the assumptions of any fiscal plan that is certified beforehand.

In a best-case scenario, Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy process won’t see a plan of adjustment until year’s end while its court confirmation could take several months after filed, according to lawyer Rolando Emmanuelli.

“Claims will come until May 21, there will be litigation on these claims, and there is the disclosure document, which must be approved, and the disclosure document is also to be litigated; if it is sufficient, if it allows the creditors to exercise their right to vote in a reasonable manner… And once it is approved, then the plan [of adjustment] comes. Sometimes it is done together. And then comes voting, opposition, confirmation,” explained the lawyer about the process in court.

For his part, John Mudd, a lawyer, agrees that the “true revision” of the fiscal plan is not the one taking place nowadays, nor the one that may occur in the immediate future, “but that which will occur within the process of the plan of adjustment.” He explained that although PROMESA doesn’t allow it to review the fiscal plan, the court can make decisions as part of the bankruptcy process that would inevitably alter its content.

“The court can greatly change the fiscal plan if it decides, for example, that you have to pay Cofina,” the lawyer said using as example the entity that receives sales tax money, currently in dispute between the government and Cofina creditors. More than a dozen lawsuits parallel to the bankruptcy case of Puerto Rico revolve around different revenue sources that had been previously used to pay public debt. While the government and the FCB seek to prove that they can dispose of these revenues as they deem, several creditors groups argue otherwise and are giving the fight in court.

The newest draft of the fiscal plan includes a cash surplus, but doesn’t provide for the payment of any debt. At the same time, it groups all revenue sources, including, for example, the sales tax money that remains under dispute in court. Similarly, the board has previously warned that the government may not have the capacity to pay debt for, at least, the next five years.

“What happens is that the order of payment [in the plan of adjustment] will determine how much goes to those who are unsecured, who are the last ones on the list. I think that if there is no money to pay the debt in five years, they would receive zero. Everyone that is owed by the government, who are not secured or priority creditors, could receive zero,” Emmanuelli said.

This investigation was possible in part with a grant from the Ravitch Fiscal Reporting Program of the Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.