Luc Despins asked U.S. Judge Laura Taylor Swain to allow him to brief on his work in the Puerto Rico bankruptcy cases during a hearing in San Juan on Sept. 13.

It was not on the agenda for the day, but the judge in charge of the largest municipal bankruptcy process in U.S. history paused for a moment, took a deep breath and let the lawyer speak. A week earlier, during another hearing, Swain had blasted Despins for having filed the previous night and without prior notice, a lawsuit that sought to stop an agreement between the commonwealth government and creditors of its Government Development Bank (GDB).

“At a minimum, a courtesy call to the court to be on the lookout for the filings so I don’t have to wake up at 6 a.m. and read about them [in the press]. A courtesy call might have been nice,” said the judge, while the lawyer stayed quiet and later apologized.

Despins rarely goes unnoticed during court hearings that are held as part of Puerto Rico’s five bankruptcy cases initiated under Title III of the so-called PROMESA law. The intensity and colloquial style with which he argues contrast with the more tempered and technical style of lawyers such as Martin Bienenstock and John Rapisardi, who represent the island’s federally appointed Fiscal Control Board and the commonwealth government, respectively.

During a court hearing held on Oct. 5 over the proposed GDB settlement, Despins and Peter Friedman, who represents the government, announced they had reached an agreement that would put aside the objections that had been raised by Despins’ clients.

“The GDB settlement guarantees that the Title III debtors [the government] will get at least $20 million and likely $30 million as a result of our work,” he told Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI by its Spanish initials), as Despins went over the range of tasks that his law firm does in Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy process.

Last in line

Despins and his law firm, Paul Hastings, represent the Unsecured Creditors Committee (UCC) in Puerto Rico’s Title III process, as well as in other matters such as the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), the Aqueduct & Sewer Authority (PRASA) and the GDB. It is a statutory committee appointed by the U.S. Trustee, and the commonwealth government, as debtor, pays for the professionals it hires, once the court green lights its retention.

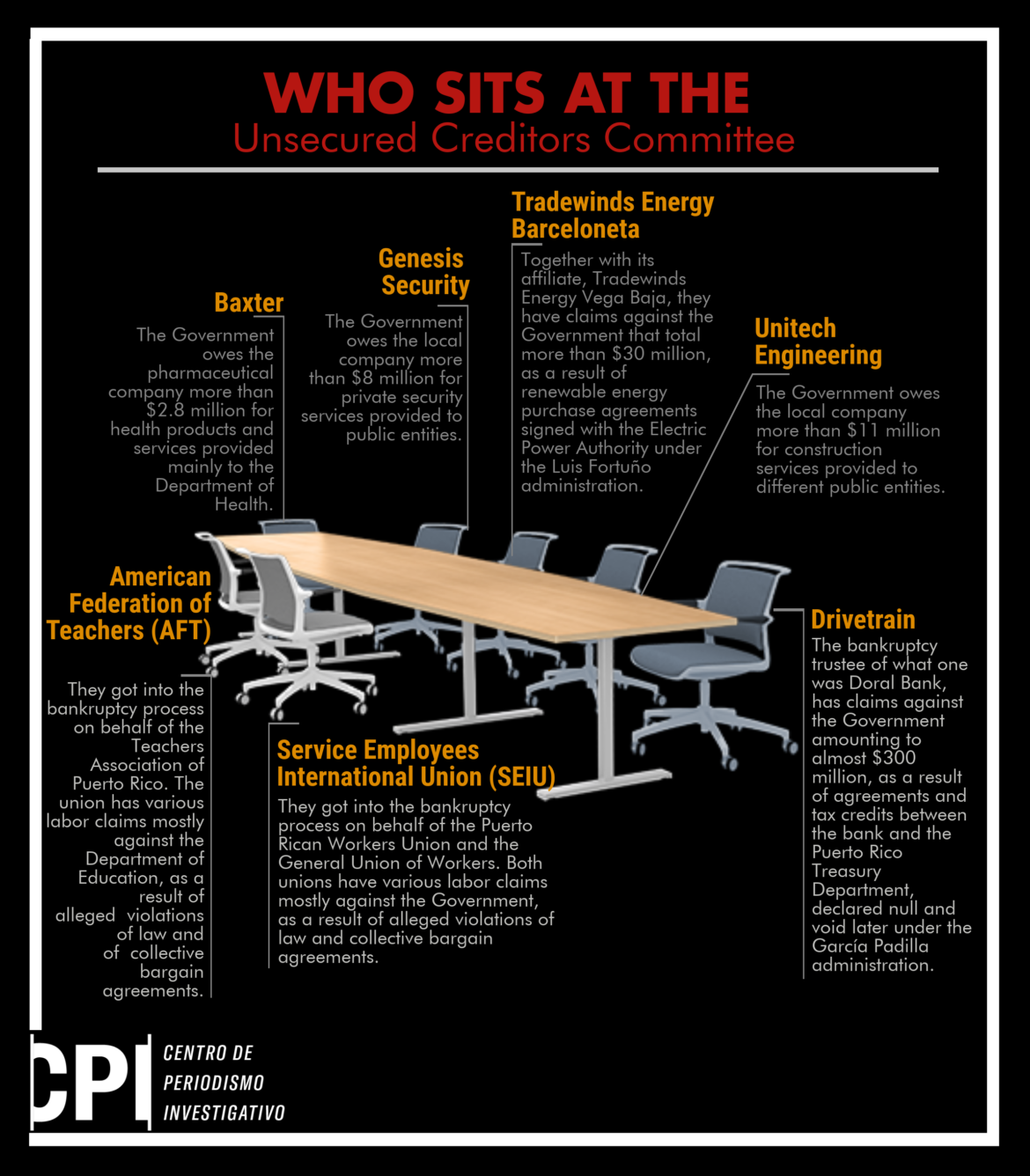

The UCC mostly includes local government suppliers and contractors, as well as two national unions that represent public employees and teachers. The Committee defends the interests of any person or entity to whom the commonwealth government owes money, but have no guarantee of repayment: from a small business that carried out work or rendered a service to a public agency, to public employees with labor claims against the government. The UCC also acts as the information agent for these creditors, assisting, for instance, in the proof-of-claim filing process by holding various informative sessions throughout the island.

Along with pensioners, unsecured creditors are typically at the end of the line when it comes to repayment in a municipal bankruptcy such as Puerto Rico’s. The UCC seeks to maximize the amount of money, the “pot,” available for paying these creditors, explained Rolando Emmanuelli, a lawyer who authored a book on PROMESA. In the island’s bankruptcy process, he represents employees and retirees of Puerto Rico’s power utility, PREPA, as well as a group of UPR professors.

“The risk is that [unsecured creditors] recover zero. [The government] could estimate that there is no money for unsecured creditors and that is why they [the UCC] have to give the fight,” Emmanuelli told CPI.

The UCC has actively participated in everything related to the restructuring of Puerto Rico’s debt, which tops almost $120 billion in debt and pension obligations. It holds accountable and calls for the investigation of the financial institutions that advised on the policy decisions that led to the island’s fiscal crisis. It puts in doubt the legality of the debt and questions the fiscal plans and budgets, actions taken by the board and the government, and the agreements struck with other creditors.

“This militant role [of the UCC] is a combination of factors: a complicated case, a powerful law firm and the will of the committee members to fight everything,” Emmanuelli said.

If Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy were a Western movie, UCC lawyers would be some sort of a Lone Ranger, whom have billed to date more than $25 million. The hourly rate of Despins — who worked in the bankruptcies of Lehman Brothers and Enron— is $1,395, billing so far roughly $2.5 million. His hourly rate is higher than his counterparts at the Fiscal Control Board and the government, according to documents filed in court as part of the Title III cases. However, the lawyers and consultants who represent the board and the government also perform work outside the court-ordered bankruptcy process, which means that not all of their billing is made public and evaluated by the court, contrary to professionals retained by the UCC.

“We agreed to a 20% reduction of the fees we are seeking in the case. No other firm involved in the case has offered as much. Second, we are efficient. We send very few lawyers to a hearing. I often appear alone while other firms have four to five partners in attendance,” Despins said.

Genesis Security, Unitech, Baxter, Tradewinds Energy Barceloneta, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the International Union of Service Employees (SEIU) and Drivetrain, the trustee of now extinct Doral Bank, currently comprise the UCC. The Committee is chaired by Alvin Velázquez, a Puerto Rican lawyer who comes from the labor union sector and briefly led the work of a failed legislative entity that sought to audit the island’s public debt.

Shadow of Doral looms over bankruptcy

Zolfo Cooper leads the financial consultancy of the UCC. It advises on the impact that fiscal plans and budgets approved by the government and the board will have on unsecured creditors, as well as on any debt-restructuring proposal. The New York-based firm adds more that $7.8 million to the bankruptcy’s professional service tab.

Zolfo Cooper worked on the liquidation of Doral Bank, a local financial institution that collapsed in 2015 amid serious financial woes. That same year, shortly before shutting down — and after the bizarre murder of one of its top officials — Doral sued the government to obtain, in cash, almost $230 million in tax credits it alleged it was owed by the local Department of Treasury, pursuant to a 2012 agreement between the Doral and the commonwealth government.

A few years later, several professionals from Zolfo Cooper related to Doral case are now advising as part of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy process. This is the case of Enrique Ubarri, Doral’s former in house counsel and now senior adviser with Zolfo Cooper, providing services to the UCC at $850 each hour.

Last year, Ubarri and Doral Bank’s former chief executive officer, Glen Wakeman, signed a $14 million settlement with the FDIC for the federal agency to desist from taking action against both officials for alleged gross negligence in handling the operations of Doral.

Also part of the Zolfo Cooper team that worked in the Doral case and now advises the UCC are Scott Martínez and Carol Flaton, who was the bank’s main restructuring adviser and now leads the UCC’s financial consultancy, charging $940 each hour of her service. Jarett Bienenstock, son of the board’s lead legal adviser, Martin Bienenstock, works in Zolfo Cooper but is not involved in the Puerto Rico matter, the firm assures in a court filing disclosing his employment.

In late September, Zolfo Cooper announced that its operations will be acquired by AlixPartners, a restructuring firm that under the command of Lisa Donahue, served as lead restructuring adviser for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority during the administration of former Gov. Alejandro García Padilla.

Retirees: lowest billing

Pensioners and retirees are among the groups that have the most to lose as part of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy. It is estimated that there are more than 160,000 pensioners, to whom the government owes roughly $50 billion.

The professionals who advise the Retirees Committee — which doesn’t include PREPA pensioners — have been the least that have billed so far in the Title III process. Led by attorney Robert Gordon and his law firm Jenner Block, the six firms retained by this committee add about $12 million in billed work, a fraction of what the leading law firms for the board (Proskauer Rose with $40 million), the government (O’Melveny & Myers with $37 million) and the UCC (Paul Hastings, $26 million) have billed. However, their big fight in the Puerto Rico bankruptcy has yet to come. Cuts to public pensions will be taken care of when evaluating a debt adjustment plan for the commonwealth government, something that is expected to happen at some point next year, according to the board and the government officials.

Miguel Fabre Ramírez, Juan Ortiz Curet, Blanca Paniagua, Milagros Acevedo Santiago, Lydia Pellot, Marcos López Reyes, Carmen Haydee Núñez, Juan Ortiz Curet and Rosario Pacheco Fontán currently comprise the Retirees Committee.

Gordon advised Detroit retirees during its Chapter 9 bankruptcy process. There, retirees saw cuts to their pensions of up to 4.5%, while losing other benefits such as medical coverage and adjustments for the increase in the cost of living. The creation of a trust, funded mainly by private entities and nonprofits, prevented greater cuts to Detroit retirees. In Puerto Rico, the board is calling for pension cuts that average 10% — almost twice as much as in Detroit — along with other structural changes to the island’s retirement systems.

Also advising the Retirees Committee are financial advisory firm FTI Consulting, actuaries Segal Consulting and Bennazar, García & Millán, a local law firm that has Hector Mayol Kauffmann, the former administrator of the Puerto Rico Employees Retirement System under the administration of Luis Fortuño.

For Emmanuelli, the role of both committees, Retirees and the UCC, is important as it gives Puerto Ricans some control in the decision-making process that occurs as part of the island’s bankruptcy. “They seek to anchor in Puerto Rico a series of important decisions,” the lawyer said, adding that these committees will play an important role when evaluating and voting over debt adjustment plans.

Paying to solve battle over sales tax

One of the core issues of Puerto Rico’s restructuring process is determining who owns future collections of the island’s sales tax known as IVU. Through COFINA, a public corporation created in 2006, the commonwealth issued more than $16 billion in bonds whose repayment was guaranteed by the IVU, a key revenue source for the government. With Puerto Rico in bankruptcy, the dispute over the ownership of future sales tax revenue — between the government and COFINA creditors — became the “gateway” issue, as Judge Swain called it, to solve the island’s bankruptcy.

On this front, the UCC has acted as the “commonwealth agent,” negotiating in favor of the government and arguing that the IVU money belongs to the commonwealth coffers and not to COFINA, much less to its bondholders. The board tasked the Committee with this job when the entity imposed by the federal PROMESA law was forced to delegate the matter amid conflicting interests in representing both the government and COFINA, a public entity.

The board and COFINA bondholders also tapped Bettina Whyte to defend the interests of the public corporation and its creditors in the dispute over the sales tax revenue. With offices in Jackson, Wyoming, Whyte has billed more than $900,000 in about eight months, at an hourly rate of $1,100.

The so-called “CW/Cofina dispute” has cost the people of Puerto Rico tens of millions of dollars, only in lawyers and consultants. In early summer, a preliminary settlement that would put an end to the dispute was announced between the two agents, the UCC and Whyte, and supported by the government and the board. It would divide the COFINA sales tax pot roughly in half between the commonwealth coffers and COFINA creditors. However, whether the UCC continues to support the agreement remains to be seen, as lawyers for the Committee have recently warned the court. The UCC claims that if the government’s fiscal plan is not revised to be consistent with the proposed COFINA settlement, they would withdraw their support.

Several years ago, Whyte worked alongside several familiar faces of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy, as part of a commission established in 2011 by the American Bankruptcy Institute to evaluate changes to Chapter 11 of the Federal Bankruptcy Code. Members of the commission included Arthur González, a fiscal control board member and former bankruptcy judge, Jim Millstein, the commonwealth’s former lead restructuring adviser, and Kenneth Klee, who is now one of the lawyers advising Whyte in the Puerto Rico case.

The COFINA agent has retained two law firms as legal advisers: Klee, Tuchin & Bogdanoff and Willkie Farr & Gallagher. Last May, the court-appointed fee examiner in the island’s bankruptcy process, Brady Williamson, raised flags on the hiring of these two firms and the duplicative work and expenses that it represents.

“The second interim review and reporting cycle has not shed more light on a core question — why does the COFINA Agent require two law firms?”, stated Williamson in his report to Judge Swain.

Klee Tuchin and Willkie Farr have billed a total of roughly $16 million for services rendered in eight months, all charged to the commonwealth government. At the same time, the COFINA agent sought to retain Centerview Partners as financial adviser, but the court stopped its hiring after Williamson questioned the need for these services.

A costly and secret mediation

In the months that followed the appointment of Puerto Rico’s fiscal board by President Barack Obama, there were many names mentioned for the executive direction of the entity. Martha Kopacz, of Phoenix Management, was one of these names.

Kopacz, who advised Judge Steven Rhodes in the Detroit bankruptcy, was no stranger to Puerto Rico. In 2015, she served as an expert witness as part of a lawsuit brought by Wal Mart against the commonwealth government, opposing a tax that was finally declared unconstitutional. Months later, she was linked to the process of organizing what would become to be Puerto Rico’s fiscal board, established in the summer of 2016.

At the end of the day, Natalie Jaresko was appointed as executive director of the board. But Kopacz would find a place at the table. Three months after Puerto Rico filed for bankruptcy under Title III of PROMESA in the summer of 2017, she was hired as a financial consultant to the team of five federal judges who lead the behind-closed-doors mediation process between the government, the board and Puerto Rico creditors. Kopacz, who charges $695 an hour, and her firm Phoenix Management have billed so far more than $1.7 million.

Próximo en la serie

3 / 4

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.