DCIM100MEDIADJI_0012.JPG

Alexis Correa Allende rides his bicycle through the Parcelas Suárez neighborhood in Loíza. He only takes his hand off the handlebars to greet his neighbors. He’s relaxed on his two wheels. That is, until he reaches 10th street of the neighborhood, where the Paseo del Atlántico used to be. Since 2012, Alexis, spokesman for the sector’s Community Board, has seen how the sea destroyed the walkway, leaving several residences much closer to the water. This situation has become increasingly worrisome for Alexis and to some 1,560 people living in Parcelas Suárez. Even more so when high tide season comes.

“Since I started this fight over the issue of coastal erosion in 2012, I live in distress. Everyone lives worried,” says Correa-Allende, 35.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

Alexis Correa-Allende has been fighting for six years to bring to life a plan that mitigates coastal erosion in Loíza.

In 2018, the United States Corps of Engineers (USACE) approved $5,170,000 in funds for a seawall that mitigates coastal erosion in this area. However, the USACE announced last Tuesday, that the construction of this project would not begin until January 2020. Alexis explained that this is the third time the starting date of the construction has been delayed, which was scheduled to start in July 2019. Meanwhile the waves continue to pound against streets 10th and 11th, increasing erosion, as was witnessed by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, for its initials in Spanish.)

To get to Parcelas Suárez there are three main entrances from Road 187 that run along the Loíza coast. The three entrances end at the beach. The sea is part of this town’s culture, where 49.6% of its population lives below the poverty level, according to the 2016 Community Survey of the United States Census Bureau. It is a community that celebrates their African heritage as in few places in Puerto Rico. In the survey, 35% of Loíza residents identified themselves as black, a figure that underestimates reality, according to several community leaders.

Parcelas Suárez is also a working class neighborhood. Of “good and resilient” people, as explained by Modesta Irizarry, a long time community leader from Loíza.

“The community has been struggling for years to obtain the services and tools necessary to counteract coastal erosion. It is a community that has been fighting since 2012 so that the Corps of Engineers and the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources do their job. It seems illogical that, if they know what they have to do, it’s been necessary to struggle so much so that they take care of the matter,” she denounced.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

For community leader Modesta Irizarry it is incomprehensible that the DRNA and USACE have taken so long to address a problem that has been evident for years.

The Parcelas Suárez Community Board has been asking the Corps of Engineers for months what kind of structure will be built, which areas will it protect, and when will the work begin. It was not until last Tuesday, July 16, that a meeting with the locals was held. However, for Alexis the process was hasty due the short time given to notify all residents of Parcelas Suárez.

“It was not fair. They [the Corps of Engineers] notified me last Friday [July 12] with only four days to notify the community. The mayor said flyers were distributed, but that is not true. Nothing was distributed. It is not fair,” denounced the community leader, who regrets that only 16 people attended the meeting. The municipality clarified that no public notice was distributed, but that it was announced by a bus with loud-speakers.

Alexis worries that in that meeting, a decision was made to favor the project without the majority of the community present. He also condemn that the Corps of Engineers staff used as an argument in favor of the project that the funds would be at risk if they are not used immediately.

At the meeting, the participants favored the project under the premise that they should prevent that the money “that with so much sacrifice they have obtained, be taken away.”

Luis Daniel Pizarro, director of the municipality’s Federal Funds Management division, questioned the hastiness of the Corps of Engineers requiring the community’s endorsement in such an expedited manner and without time to evaluate other construction options or models.

“I have always been surprised how transactional this all sounds. It saddens me that the federal government is willing to invest to protect property, but not life. I think the priorities are twisted,” said Pizarro.

The sea wall will only cover an area of 1,050 feet of the shoreline in front of a public school, a community center and a park located on 11th Street. The project left out the sector’s 10th street, which has also been affected and where about 50 people live in 15 houses.

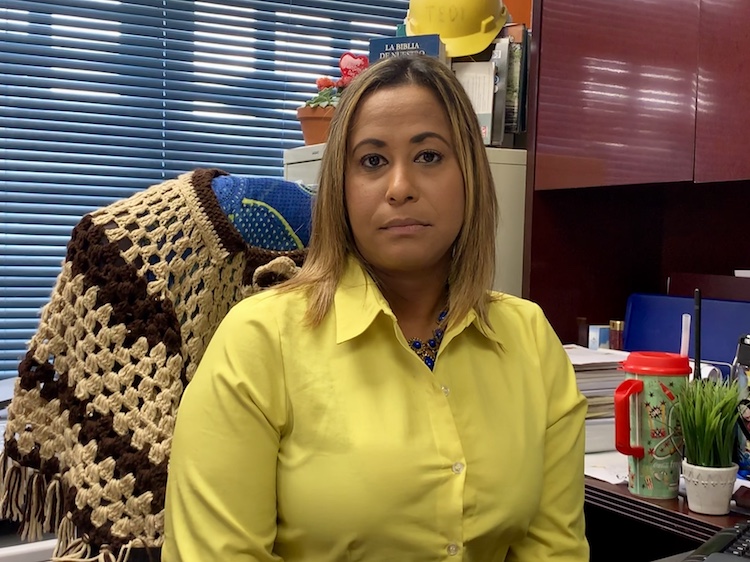

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

Loíza Mayor Julia Nazario.

The exclusion of that area, led Loíza’s mayor, Julia Nazario, to request from the Corps of Engineers an analysis on how the proposed breakwater will impact the displacement of water into neighboring communities that are also vulnerable to the sea.

Last July 15, the Corps of Engineers published an extension to the Final Integrated Viability Report and Environmental Assessment, to receive comments from the public until Aug. 14. The document is limited to explaining that the proposed sea wall received the endorsement of the Puerto Rico Coastal Management Program in 2018 and that on July 2, 2019, the Corps of Engineers submitted a request for a water quality certification before the Quality Environmental Board, to minimize adverse impacts to the quality of the resource during the construction of the breakwater. In addition, it exposes various scenarios to protect maritime life in the area and the public infrastructure. It does not include, however, the evaluation requested by Nazario regarding the impact this structure will have on the diversion of water to close neighborhoods. Neither does it include a scale model to illustrate what the project would look like, said coastal management expert Pedro González.

Sheila Hint, project manager for the Corps of Engineers, could not be conclusive as to the impact that the structure will have on nearby areas left unprotected. The swell in the area is so dynamic that the engineers cannot quantify if the breakwater will further increase erosion in other places along the coast, said Hint quoting the engineers.

The Corps of Engineers only looks over public structures and once a project is approved, it cannot be amended, relocated or extended to other areas, according to Hint. Alexis does not understand why they want to protect the school and the community center since both structures are practically ruins. Hint explained that these structures are the justification for the use of funds allocated to the area. Demolishing them would mean that there would be no public structure that merits the work of the Corps of Engineers at the site.

Alberto González, project manager for the Corps of Engineers in Jacksonville, urged the municipality and the community to seek other mechanisms to obtain more funds to protect the rest of the neighborhood’s coast. He said that the USACE has other types of assignments that can be requested for the Loíza coasts.

In addition to Parcelas Suárez, the municipality’s entire coastline has been impacted by erosion long before and after Hurricane Maria in September 2017, according to geomorphologist Maritza Barreto- Orta. Loíza Deputy Mayor Luis Ortiz-Escobar acknowledge that addressing all affected sectors would entail a multi-million dollar investment.

But residents and municipal government staff question why Loíza was excluded from a new proposal by the Corps of Engineers to carry out mitigation projects in Puerto Rico’s coastal areas affected by erosion, which would mean more funds and resources for coastal infrastructure works.

This is the Storm Coastal Risk Management Study: An integrated feasibility study and the National Environmental Policy Law, whose initial study phase will be extended for three years at a cost of $3 million.

According to Carolina Burnet, an engineer in charge of planning the study, the analysis will be carried out in seven vulnerable areas in Rincón, San Juan, Mayagüez and Humacao. Vega Baja, Arecibo, Aguadilla, Aguada, Añasco, Mayagüez, Cabo Rojo, Loíza and Luquillo, also coastal areas, were considered but left out. According to Burnet the selected municipalities were recommended by the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources. The head of this agency, Tania Vázquez, did not respond to an interview request from the CPI to find out what were the criteria used for the selection.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

Carolina Burnette, engineer in charge of the USACE study

In written statements, the DNER explained that they “provided access to information on coastal dynamics, oceanography, flood maps. All the sites identified for evaluation, analysis and modeling were visited, logistical support was provided and we remain in permanent communication with USACE researchers, engineers and planners.”

Recent studies by Barreto Orta — who has more than 25 years of experience evaluating Puerto Rico’s coasts — show that Loíza is an area much more vulnerable to coastal erosion than the other municipalities chosen. Why was this town not included? The CPI questioned Burnet.

“These are large projects with high costs and the infrastructure to be protected must be accordant with that investment. Loíza does have a lot of need, but Loíza has a low density in comparison to the other selected municipalities,” explained the engineer. The density to which Burnet refers to is structures, not population.

Yeidi Escobar, Planning director of Loíza, questioned whether the value of a structure should be given higher priority than the welfare of the people.

“The economic aspect is not a justification. I don’t see how the return on investment is more [important] than the risk of our citizens. I cannot justify that, considering that Loíza is a place of so much [coastal] risk,” said Escobar.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

Escobar, director of planning for Loíza, does not understand why the DNER and USACE give priority to abandoned structures in their mitigation plan.

Among the criteria for selecting the areas to observe, the Corps of Engineers evaluated the economic, environmental and recreation characteristics of each area recommended by the DNER.

“For a study of this magnitude, which implies federal participation of 50 years, the economic justification is very important because the project selected will be implemented and maintained for 50 years. If the cost of the project is very high, the benefits must be even greater. We consider the value of the infrastructure: buildings, commercial establishments… that go along the beach areas that are being appraised ,” Burnet said.

Puerto Rico has 799 miles of coastline, of which, 30% are beaches, 28% vegetation. In 18% there is infrastructure and in 15% there are rocks, according to Professor Barreto-Orta.

In the selected area, there are about 748 structures, between homes and commercial spaces, Burnet said. However, the engineer acknowledged that she has no estimate of how many people live in the chosen areas.

The number of people affected by erosion should be a key element when considering the coasts, said Barreto-Orta. It is essential to know if there are people living under poverty levels, if there are female led households, living there, minors, the elderly, in short, all the elements of social vulnerability, said Barreto-Orta.

The professor of the University of Puerto Rico‘s School of Planning, questioned that the Corps of Engineers study prioritizes the returns of economic investment based on the value of the infrastructure and not on the demographic characteristics of the population.

Although she acknowledged that the places chosen by the federal agency are vulnerable areas, when other social variables are taken into consideration, the data shows that there are municipalities that are more affected by coastal erosion and whose residents are in greater danger.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

Dr. Barreto-Orta believes the USACE study does not include all the necessary municipalities for in-depth knowledge of the impact of coastal erosion in Puerto Rico.

“If they asked me where I would use recovery funds, to mitigate and protect infrastructure and communities, I would say Loíza, Arecibo, Barceloneta, Humacao, Mayagüez and Rincón,” said the expert .

Barreto-Orta’s most recent analysis suggests that the area of greatest risk in the event of an atmospheric event is the coastal strip of Arecibo between the San Luis, García, Barrio Obrero and Radioville sectors.

José Vega has lived in Barrio Obrero for the past 35 years. His backyard faces the beach. After the hurricane, he lost a considerable amount of land. There, several palm trees staggered towards the void. “One of these days, while sleeping, we’ll wake up drifting at sea,” he joked half seriously.

The main entrance to Barrio Obrero in Arecibo is almost always overlooked from Highway PR-2. It is a central slope that leads to the sea. To the sides, there are three streets — Ledesma, Caribe and Cruz Roja — which house around 100 structures, several in neglect. Cruz Roja Street is the closest to the beach.

According to Vega, erosion of the neighborhood’s coast increased substantially after the hurricane. He stated that municipal staff visited the area at that time. But two years later “nobody has returned.”

According to Jose, his sector should be a priority in coastal protection efforts against erosion. But he has already thrown in the towel “Why are we going to do anything, if they’re not going to listen to us?”

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez-Velázquez | Center for Investigative Journalism

José Vega feels the government has abandoned the important task of mitigating coastal erosion in Arecibo.

For planner Ivis García, the problem with the Corps of Engineers is that they operate with a long-term logic, so they give priority to the usefulness of the buildings. However, she questioned how this vision of the future keeps marginalizing neighborhoods that have been overlooked.

“The government or those in decision-making positions must consider not only how to increase community participation, but also how to repair the damage done to the communities. Loíza, for example, which has an Afro-Caribbean population, has suffered many injustices. When you think about social injustices, you should conclude that these communities should have priority [for these types of projects],” said the professor at the University of Utah.

For García, selecting Rincón, for example, denotes a preference for communities with more economic power. Rincon is a world wide renowned surfers’ spot.

Social metrics should be the standard when planning infrastructure projects, said Garcia. She explained that disciplines such as planning, are focused on looking for options that help repair damage to communities that have historically been marginalized. Therefore, she urged the Corps of Engineers to incorporate this change of perspective to include and promote environmental justice for the communities.

Being part of this new study by the Corps of Engineers is a challenge, according to several Rincón residents.

On June 18, the Corps of Engineers presented the study before a group of Rincón and Mayagüez residents. That night, uncertainty about the possible relocations of people or entire communities was one of the concerns expressed by the neighbors.

“How will you buy property? There are people who are worried, because their family has been on the coast for a long time. Here in Puerto Rico people are different if they live on the coast. [I wonder] what measures are going to be taken to prevent environmental injustice [and] that people are displaced,” said Mari Mar Bonet, a Rincón resident.

Although the Corps of Engineers said that the decision about which projects will be completed in each area will not be made until the analysis is finalized in 2020, they did not rule out the displacement of people due to the expropriation or purchase of their properties.

Milán Mora, another spokesman for the Corps of Engineers, explained that relocating people or communities is considered as an alternative when it is more expensive to build infrastructure that protects those houses. However, he said these movements of people or communities must follow the regulations of the U.S. Uniformed Relocation Law, which requires guaranteeing fair compensation for those whose property is expropriated by the government .

In the case of larger buildings, other mitigation or conservation alternatives would be evaluated.

“We cannot relocate a large 20-story structure in San Juan, because it will not be cost effective. It is easier to protect that structure before removing it. But if we are talking about one, two or three houses, where the cost is small, compared to the cost of putting sand or a breakwater, [relocation] may be one of the alternatives,” Mora explained.

García, and Professor Barreto-Orta agreed that the problem with relocation is that it is done without considering environmental justice or the right of communities to participate in making decisions that directly affect them.

According to both professors, in Puerto Rico, the communities are informed once the decision is made, leaving them out of the analysis and determination process.

“The concept of relocation has been demonized. But this has to be a course of action when protection alternatives do not guarantee the safety of communities. However, we must understand that the relocation process must be combined with a protocol that makes it clear that the decision was made, not just by the municipality and the state, but also by the community,” Barreto-Orta said.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau Community Survey, in 2017, 44.9% of Puerto Rico’s population lived below the poverty level. This results in disadvantaged communities being more likely to suffer environmental injustices while having fewer tools to avoid and mitigate impacts, according to the National Association of Environmental Law (ANDA in spanish).

Despite the concerns, the spokesman for the Corps of Engineers emphasized that some determinations — such as the relocation of people — are not being discussed now and that it will be evaluated based on the study’s conclusions. The proposals of relocation, if any, will have to go to the U.S. Congress, to fund those projects. According to Mora, this process could take up to seven years before they begin any relocation project.

Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez is a Report for America member.

8 septiembre, 2022 LEER MAS