The Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) is evaluating different alternatives to obtain more information about the agreement between two of the main companies that operate at the Puerto Nuevo, San Juan, cargo pier.

However, the chairman of the federal entity, Michael A. Khouri, warned Gov. Wanda Vázquez Garced that if, as it seems, the transaction is actually a merger of companies or a purchase of assets, the FMC may not have the authority to stop the agreement between Luis Ayala Colón (LAC), the company responsible for loading and unloading international ships at the Puerto Nuevo pier, and Puerto Rico Terminals, a subsidiary of Tote Maritime, the second-largest company that operates the domestic cargo terminals in the Port of San Juan.

The FMC’s concern over service being affected and that freight costs to and from Puerto Rico would be increased was expressed by Khouri in a letter he sent to Vázquez on Oct. 1.

The “Commission will insist on enhanced monitoring with extensive disclosure of business and marketplace information. The Commission is also exploring other avenues to develop additional information about the agreement,” such as an investigation and hearing or a special report, “(known as a Section 15 Order) requiring the parties to provide information to the Commission,” Khouri said in his letter to the governor, which her office, La Fortaleza, made available to the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI by its Spanish initials).

Khouri was responding to the letter Vázquez Garced wrote to the FMC on Sept. 19, requesting it to intervene to ensure the transaction between Puerto Rico Terminals and LAC does not affect consumers on the island.

The governor told the commission that although former Gov. Ricardo Rosselló González did not object to the transaction and refrained from submitting comments about the possible impact on the market and the island’s economy, given the concern expressed by several sectors, she must ensure “this transaction does not adversely impact the people of Puerto Rico.”

If the FMC lost jurisdiction, both the U.S. and Puerto Rico departments of Justice could intervene because the controversy would become about the possible concentration of economic power, which involves problems with the exercise of free enterprise.

“That would be the responsibility of the antitrust division of the Department of Justice of Puerto Rico and federal Justice,” explained the expert in corporate law and former director of the Ports Authority, attorney Carlos Díaz Olivo. The legal fight, the lawyer said, could be initiated by either the Government of Puerto Rico or an affected competitor.

The local Justice Department has had an investigation into the transaction underway since April.

The cooperative working agreement to create a new company, Puerto Nuevo Terminals, was presented to the FMC at the beginning of 2019. Ports Authority Director Anthony Maceira said the Puerto Rico government learned about the transaction in March, and on Rosselló González’s orders remained on the sidelines and presented no opposition. The issue was also not considered by the Ports’ board, Maceira said in his deposition to the House Committee on Federal Affairs, which is investigating the possible impacts of the agreement.

Under the Puerto Nuevo Terminals LLC (PNT) Cooperative Working Agreement, LAC and Puerto Rico Terminals (PRT) form PNT, with its membership units held 50/50 by the two owners. PNT will acquire, through assignments, leases, subleases, transfers and other corporate means, all terminal services agreements, land leases, cranes, yard equipment and other related assets from the LAC and the PRT, according to the document presented to the FMC. Much of that equipment belongs to TOTE Maritime, co-owner of the PNT.

TOTE is in turn part of Saltchuk Resources, an umbrella company that includes Foss, Northern Aviation Services, Hyak Supply Chain, Tropical Shipping and NorthStar Energy.

According to OpenSecrets.org’s database of campaign contributions, between 2015 and 2019, Saltchuk donated $15,500 to Resident Commissioner Jenniffer González’s campaign. Among donations González has received through political action committees (PACs), Saltchuk is the main contributor, followed by Crowley Maritime and Seafarers International Union. González said she has no comment on the agreement because it is a matter of “pure state jurisdiction.”

LAC is in the process of negotiating a collective bargaining agreement with its employees.

When PNT starts operating, it will be responsible through its single management team and board for negotiating and entering into all terminal services agreements, crane and other yard equipment purchases or leases, coordinate labor for on-dock stevedoring and all other matters related to the operation of a marine container terminal. At that time, LAC and PRT will “withdraw from that business, leaving the PNT and Crowley…as the only two container terminal operators” in Puerto Rico, as put by the FMC.

The agreement to create PNT entered into force Aug. 29, but as of press time, the company did not yet appear as incorporated in the State Department registry, although the name does appear separately.

Despite its concerns, the FMC allowed the transaction, as its members “did not reach consensus on the threshold question of whether the agreement comes within Shipping Act jurisdiction. Next, a majority could not determine that we have enough information and evidence at this time to go to Federal Court to seek an injunction to prevent this agreement from going into effect. We understand what the parties are trying to achieve, but serious concerns remain about the implementation of the agreement,” Khouri previously explained.

The FMC is composed of four members, all appointed by the president of the United States.

Although its meetings are mostly public and can be accessed online, when passing judgment on the PNT agreement, the commission conducted its vote through an alternate procedure, according to the Federal Register.

“The PNT agreement was done as a ‘notation item,’ [with] each commissioner submitt[ing] a vote sheet with his or her vote. Considering items by notation is a common procedure at the FMC for handling agreements and is done frequently. There was no meeting where the PNT agreement was subject to a vote,” the FMC told Caribbean Business.

Control over port activity in Puerto Rico is not only an element that defines the economic situation of the island, but is also a matter of survival.

After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, diaspora groups organized to send supplies to the island. One of those groups was the Sunset Park Relief organization in New York. It had begun collecting supplies for those affected on the island after Hurricane Irma two weeks earlier. Two months later, sending supplies was still urgent.

The cargo was valued at more than $1 million, and they were charged $7,800 to transport it from Jacksonville, Fla., to Puerto Rico a month after Hurricane Maria. The Sunset Park Relief Coalition in New York had begun collecting supplies for those affected on the island after Hurricane Irma, and two months later, it was urgent to send these.

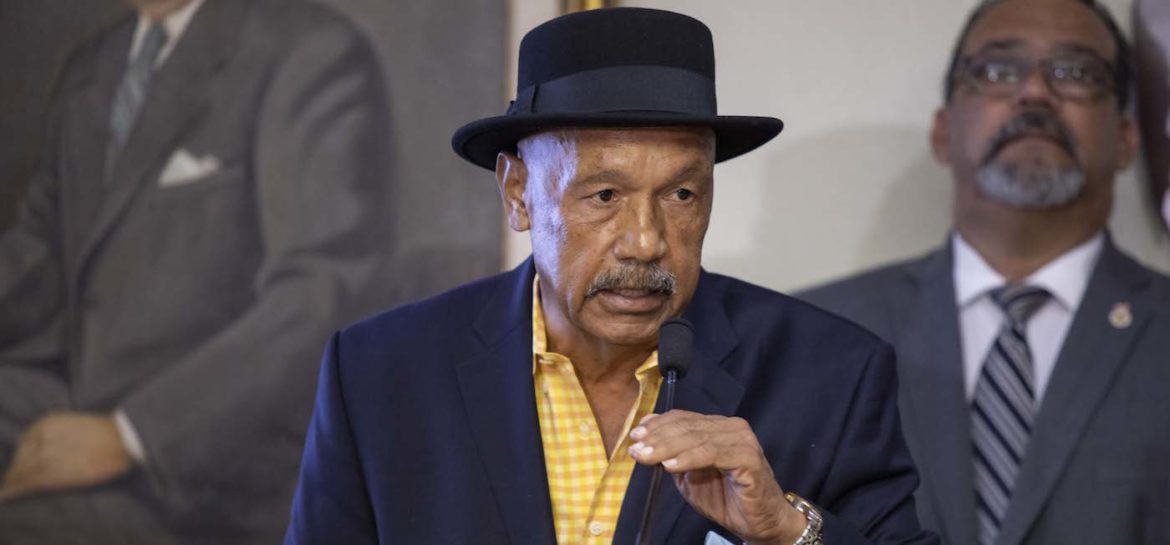

“In the hurricane, I paid. I did. They didn’t tell me; I paid $7,800 for a [cargo] container to Puerto Rico…. That’s a lot. That’s $7,800 for a container from Jacksonville to here,” said an indignant Germán Vázquez, president of the Transportation & Attached Branches Union (UTRA by its Spanish acronym), who in coordination with Sunset Park organized the transportation and distribution of aid to hurricane victims.

Photo by Juan José Rodríguez | Caribbean Business

Germán Vázquez, president of UTRA

The amount paid was three and a half times more than the average estimated cost for this type of transportation using U.S.-flagged ships and 10 times more than shipping the merchandise using international vessels.

According to a survey by Advantage Business Consulting—commissioned this year by the Chamber of Food Marketing, Industry & Distribution (MIDA by its Spanish acronym)—a 40-foot container that transports non refrigerated cargo from Jacksonville to Puerto Rico has an average cost of $2,114 using U.S.-flagged ships, or $755 using international ships.

Among the stories about the aftermath of the recent hurricanes, one that is repeated frequently, is related to the problem of handling merchandise and donations at the piers. The issue has again become part of public discussion with the recent announcement of the concentration of power in the island’s ports—in the hands of practically two companies—Crowley, which operates eight vessels, and Tote Maritime, which runs two ships on a regular basis.

Maritime shipping companies are governed by the U.S. Shipping Act, which establishes the general rules under which the industry operates, and leaves the responsibility of establishing the applicable regulations to the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC).

When the Puerto Rico government sold its shipping companies in the 1990s, about 30 were operating on the island. That number has dropped to only four: Tote Maritime and Crowley, which between them serve 95 percent of the maritime cargo; as well as Trailer Bridge and National Shipping. These four companies transport merchandise, or commercial, industrial and private supplies, which arrive or leave the island on U.S.-flagged vessels and are subject to the Jones Act. While marine support services company Luis Ayala Colón (LAC) attends to cargo that arrives on international ships.

The Puerto Rico Ports Authority is the local government entity called upon to ensure the island’s air and maritime infrastructure serve the needs of the people of Puerto Rico—with the right to develop, own, upgrade, operate and manage them. However, in the case of the piers, it is Ports’ duty to ensure their operation does not hinder or threaten economic development by jeopardizing the entry or exit of commercial and industrial supplies, according to Act 125-1942, as amended.

Under Ports’ purview, there are 37 piers around the island. The Ponce, Mayagüez and Ceiba piers are under the jurisdiction of the Municipality of Ponce, Mayagüez Port Commission and Maritime Transportation Authority, respectively. Only the Puerto Nuevo and Isla Grande piers in San Juan are used for general cargo, or consumer goods and supplies for companies operating in Puerto Rico. Only light cargo comes through Mayagüez and Ponce.

TOTE (formerly Sea Star), rents the Puerto Nuevo pier, which pays the government $35 million for its lease, from December 2012 to 2032.

Through its Puerto Rico Terminals (PRT) subsidiary, TOTE provides cargo services to Trailer Bridge and National Shipping vessels. International ships are served by LAC employees.

The Isla Grande Pier, nearly 79 acres at the former naval base in San Juan, is leased to Crowley for $56 million for the period of September 2016 to September 2046. Crowley has the largest operation on the island.

Asked if both companies are up-to-date with their payments, Ports Authority spokesman José Carmona referred the question to the legal division.

In the interview for this investigation, Eduardo Pagán Reyes, TOTE vice president & general manager, Caribbean Services, Puerto Rico, and president of the Puerto Rico Shipping Association, acknowledged that the island’s maritime cargo industry operates as an oligopoly, or a system in which the number of sellers is very small and, thus, control and corner sales of certain products as if they were monopolies.

“Many people make the comment that this is a monopoly. No, this is not a monopoly; it is an oligopoly. A monopoly would be a single company, when you have two, three, four, maybe you can call it an oligopoly. What people don’t know is that here there are more than 20 [U.S.] American companies that could come to Puerto Rico and establish operations, but the investment they would have to make is in the $1.5 billion range. This is not selling cellphones in a corner. These are not just ships—we are talking about ships, equipment, containers, cranes—the array of expenses is significant,” he added.

Eighty percent of the merchandise that leaves or arrives in Puerto Rico comes from the Port of Jacksonville. The other ports with service to the island, although on a smaller scale, are Pennsauken, N.J.; Houston and Philadelphia.

In 1996, however, Puerto Rico also received merchandise from the ports of Elizabeth, N.J.; New Orleans, Miami, South Carolina, New York and Baltimore.

The laws of Puerto Rico establish that the island’s ports and piers are in the public domain and cannot be sold to private entities. Until 1994, the ports were operated by the Puerto Rico Maritime Cargo Transportation Authority. That year, the government created a public corporation, Navieras de Puerto Rico, which assumed that responsibility until 2001, when it filed for bankruptcy, after which, Sea Star Line Agency (SSA) acquired the contract Navieras had with the Ports Authority in December 2012.

The contract was signed by the vice president & general manager of Sea Star, Eduardo Pagán Reyes. The agreement granted that company the use of about 59 acres in the Puerto Nuevo area of the San Juan Port, for a $35.4 million, 10-year lease with the option to extend it twice for an additional five years, or a total of 20 years.

In 2006, Sea Star established a joint agreement with the other shipping companies that use the Puerto Nuevo pier so LAC, National Shipping, Island Stevedoring, Horizon Lines and Trailer Bridge could dock and use SSA’s facilities and cranes.

The agreement with SSA was amended in 2016 to stipulate the company had become TOTE Shipholdings, which thereafter assumed the contract to operate the Puerto Nuevo pier.

For its Puerto Rico business, TOTE has two ships and six cranes for loading and unloading cargo from its ships and Trailer Bridge and National Shipping’s barges. Port operations for TOTE, Trailer Bridge and National vessels are offered through the PRT, which is also run by Pagán Reyes.

For its local operations, Crowley has four ships and four barges, cargo containers, three cranes, and trucks for land transport through its subsidiary Crowley Logistics.

In 2013, federal Judge Daniel R. Domínguez sentenced the former president of Sea Star, Frank Peake, and five other people to serve prison sentences, ranging from seven months to five years, for their participation in a conspiracy to fix rates and surcharges for freight shipped from the Jacksonville Port to Puerto Rico between mid-2005 and April 2008.

Thomas Farmer, former vice president of price & yield management of Crowley, was indicted in March 2013 for his role in the conspiracy but a jury acquitted him in May 2015.

The executives and three companies (Sea Star, Crowley and Horizon Lines) involved in the price-fixing scheme have paid more than $46 million in fines for their participation in that conspiracy, which included setting freight service rates, rigging bids submitted to Puerto Rico freight services customers and other practices in violation of the antitrust laws of the maritime shipping industry.

Finding information about these companies’ operations is an ordeal because they are mainly governed by the Shipping Act, which was amended in 1984 to deregulate the industry.

As recently as Oct. 1, a Surface Transportation Board (STB) order entered into force that requires shipping companies to make their rates accessible to the public. The website to see TOTE’s rates is www.totemaritime.com/tariffs/. There, visitors can see the rates for several customers after signing in with a provided username and password. Finding out the rate for a specific shipment is very complicated.

“The numbers [rates] we have are from a survey [of importers and exporters]. The official data are not public,” said Manuel Reyes, vice president of MIDA.

Photo by Juan José Rodríguez | Caribbean Business

Manuel Reyes, executive vicepresidente of MIDA

The MIDA survey by Advantage Business Consulting found the average cost for a dry container (which is not refrigerated) is $2,114, while a refrigerated container could cost about $5,210.

Through its spokesperson in Puerto Rico, Nelly Cruz, TOTE told Caribbean Business and CPI that its cargo rates “vary depending on several factors, including volume and the type of product shipped, the season, equipment required and many other specifications. Almost all freight shipped by TOTE between Jacksonville and San Juan is defined within confidential shipping agreements, or contractual rates.”

In Crowley’s case, the company provides basic rates on its website, but reaches private agreements with most of its regular clients, an STB spokesperson confirmed.

“There should at least be statistics but, unfortunately, there are none. Puerto Rico lives with its back to the island’s reality. The Department of Economic Development cannot go to an investor and tell them how much the freight costs are to and from Puerto Rico,” Reyes said.

When asked about the rates that inform potential investors, who want to come to the island and establish a manufacturing plant, for example, Economic Development Secretary Manuel Laboy indicated he understood the rates were published on the respective shipping companies’ websites.

“For [Hurricane Maria], in theory, the importers had a contract with their transportation company, with a price that was already established, but what would happen is they would be told: ‘I have no capacity, so I cannot bring it to you,’” Reyes explained about businesses which, despite having contracts with a shipper, were told after the hurricanes that there was no room in their vessels, but the merchandise could be brought in rented ships, which raised the previously agreed pricing.

Asked about businesspeople who could be interviewed and provide evidence about this practice, Reyes replied: “To the extent that none of this is regulated, and is so monopolized, those affected are afraid to speak because they depend on those companies to bring in their goods.

“An importer who has no control or bargaining power because he is fighting against an oligopoly, if he faces them, the danger of an adverse reaction is too great. They say it in private, but they won’t say it publicly,” MIDA’s Reyes added.

In an interview with Caribbean Business, TOTE’s Pagán Reyes said the rates and reports on the shipper’s operations are periodically submitted to the Ports Authority and Treasury Department.

For this investigation, Ports was asked to provide the number of containers and cargo moved from 2016 to date. It sent a table with the total load per year but not by the company, nor a detail of the monthly movement.

When asking about the rates, the Ports’ spokesperson said that specific information was not held by the agency.

Ahead of a new emergency

In the state of Florida, the Puerto Rican Professional Association (Profesa) recently established an initiative—with the support of Jacksonville Port and shipping companies—to educate community groups about the procedure for sending donations to Puerto Rico in case of an emergency.

Rafael González, president of Profesa, admitted that after Hurricane Maria, many of the donations never left the port, although he could not give specific numbers. He explained that some donations had to be returned due to lack of funds to pay for shipping to the island and others because they were not documented as required by federal law.

“When Maria [hit], the diaspora here [stateside] overwhelmingly gave donations and then did not know what to do with them,” said Dr. Thomas Agrait, Profesa’s vice president of Governmental Affairs.

Agrait said that after Hurricane Maria, TOTE and Crowley would charge $5,000 to $6,000 for a shipment of unrefrigerated donations to Puerto Rico.

González said they met with the administrators of the Port of Jacksonville to define protocols to expedite these shipments in emergencies. He also said that when he met a week ago with Puerto Rico Ports Director Maceira, he said any related negotiation should be done with the companies that operate the Tote and Crowley piers.

Agrait said the issue of rates for that cargo was discussed at that first meeting. “We know the rates are a crucial issue and we prefer to leave them aside to be more effective, but it is not something we should ignore facing the future,” he said.

Hands off

Puerto Rico Ports Authority Director Anthony Maceira admitted there is a need for the government to take a more active role in controlling operations, which was discussed with the private sector just after Hurricane Maria.

“But the reality for decades in Puerto Rico has been that [the ports] is operated by private entities,” he said.

Likewise, he stressed that even when wanting to change public policy so the government retakes control of operations at the piers—as it did before Navieras was sold—the island’s financial reality prevents making an efficient operation viable.

When questioned about Ports’ debt, Maceira did not want to go into detail about current figures, alleging the authority is amid negotiations with its creditors. However, in a statement, the Fiscal Agency & Financial Advisory Authority wrote that the pre-agreement with bondholders includes those issued through the Infrastructure Financing Authority (AFI by its Spanish acronym) for the benefit of the Ports Authority, and an interagency Ports loan with AFI for $190.6 million.

The Ports Authority debt, including the AFI loan, totals $455 million. The agreement for the debt has been extended several times, the agency said, as it “continues to work with internal approvals, that of the Fiscal Oversight Board and the process of gathering information necessary for closing the transaction.”

“We will always be watchful that the business that is done complies with the law and, if at any time something is detected that we understand is outside the [legal] framework, we would make the relevant referrals because we do not have jurisdiction to enforce compliance. And I have to be very careful with what I say in that regard because what I say or don’t say can have an effect on the market and I have to be responsible in that regard,” Maceira said.

Questioned about the PNT joint venture during a public hearing held by the island’s House of Representatives, Maceira admitted he did not raise concerns with the FMC about the transaction despite it threatening to increase the oligopoly in that industry, nor did he bring up the transaction with Ports’ government board for evaluation.

Part of the Ports agreement includes using the revenue generated by leasing the Puerto Nuevo area property that Puerto Rico Terminals uses for its operations as a partial source of repayment for bonds issued in the future. In return, the creditors will contribute new capital for capital improvements, in addition to using 10 percent of the annual income of said properties for capital improvements through the 25 years considered in the debt-restructuring agreement. The negotiation also requires a valuation of this income, which is still underway.

In a statement in August, one of the FMC commissioners, Daniel B. Maffei, said the PNT “agreement certainly reduces competition, so the question is whether there is a likelihood that this reduction in competition would produce either an unreasonable reduction in transportation service or an unreasonable increase in transportation cost, or substantially lessen competition in the purchase of certain services.”

Besides the FMC chairman, Maffei was the only commissioner who issued a public statement opposing the agreement.

Crowley and TOTE operations include rentals of cargo containers to transport on their vessels from Puerto Rico to the ports of Jacksonville, Houston and Philadelphia, and back; the unloading of freight and its storage, if necessary; and cargo delivery to customers.

Some of these companies, such as Trailer Bridge and Crowley, provide door-to-port or door-to-door service, which is taking merchandise from the customer’s door to the door of the recipient in Puerto Rico or from the stateside customer’s door to the pier in San Juan.

Commissioner Maffei voted against the agreement, arguing the potential effects were reason enough to intervene. He pointed to the fact that the parties in the new agreement are both carriers and pier operators, saying the “consolidation of purchasing power” in the Port of San Juan could put newcomers “at a substantial disadvantage and thus trigger a violation of the new prong of § 41307(b)(1) created by the [Frank] LoBiondo [Coast Guard Authorization] Act,” which covers antitrust restrictions on cooperation between ocean carriers and marine terminals on harbor services.

“Given that a major party to the agreement is itself a carrier, it may have incentives to keep other carriers out and would therefore not limit price increases based on this tension. Furthermore, if a carrier found the prices too high in Puerto Rico as a result of this agreement and made the business decision to stop service, it may not have a substantial negative impact on that carrier because Puerto Rico is a small portion of overall trade for any major carrier, but it could conceivably lead to an unreasonable reduction in service to the people of Puerto Rico,” he added.

The governor said in her letter to Khouri that she instructed the island’s Justice Department, “specifically the Antitrust Division, to continue its ongoing investigation” to “ascertain any violations of Puerto Rico’s antitrust statute.”

Khouri responded that the FMC was working on a statement to present to the Justice Department, but reminded her that the “Commission is prohibited from sharing some information by statute and for several other reasons I know you will understand related to the operation of a deliberative body. I assure you, however, that the Commission will be as responsive as possible to your interests and agency’s request.”

This story was made possible in part by a grant from the Center for Investigative Journalism with the support of Internews, the Center for Disaster Philanthropy and NetHope.

8 septiembre, 2022 LEER MAS