Jayuya Mayor Jorge González Otero. Photo by Juan Alicea | Center for Investigative Journalism

Jayuya Mayor Jorge González Otero speaks openly. In May, he told the top officials in charge of Puerto Rico’s recovery that they should “slash” the contract granted to stateside firm ICF Incorporated.

His anxiety isn’t unfounded. It’s based on significant reasons, or rather, a significant amount of funds. With $250 million in a federal obligation, Jayuya is the municipality with the most funds available to reconstruct buildings, roads, and bridges. San Juan follows, with $96 million.

“Those people [ICF Incorporated] don’t do any work, and if they work, they change their minds and instructions every day,” said the mayor affiliated with the opposition Popular Democratic Party about the company’s performance, which since 2018, has landed $406 million in contracts with the Puerto Rico Department of Housing and the Central Office of Recovery, Reconstruction and Resiliency (COR3) to advise and provide administrative consultancy to municipalities and government agencies to get funds. “It’s not good. It’s a major roadblock.”

Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority Executive Director Omar Marrero, flanked by COR3 Executive Director Manuel Laboy Rivera, and Housing Secretary William Rodríguez Rodríguez heard the mayor during the meeting to follow up on the needs of the municipality caused by Hurricanes Irma and María. Laboy claimed to have admonished ICF.

González Otero’s other concern is the significant damage to the roads that lead to Jayuya, in the central mountains region, which are the central government’s responsibility. Every time he knocked on the doors of the Department of Transportation and Public Works (DTOP, in Spanish) and the Highways and Transportation Authority during the previous administration, he claims that former secretary Carlos Contreras told him, “The matter is resolved.”

A few months ago, DTOP staff told him they identified 56 sections of the roads that were damaged, but the municipal staff filed a report that claims that after carefully inspecting the sites and identifying broken gutters, landslides and affected sewers the real number is 115. “No one had told us the truth,” the mayor complained.

Four years after hurricanes Irma and María, González Otero’s complaints gain strength when other mayors say they face similar obstacles, which — coupled with the increase in the cost of materials, the lack of labor, legal lawsuits against insurers for non-compliance and confusion in bureaucratic processes — delay the recovery period.

Only 1% of the funds obligated by FEMA for permanent work projects have been disbursed, according to an analysis by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) of the data published on the COR3 website. As of early September, FEMA had obligated $19 billion for permanent works. COR3 disbursed $217 million of that amount among municipalities, agencies, and private nonprofit organizations.

Puerto Rico was allocated $62 billion in recovery funds from FEMA, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and 17 other federal entities. The biggest amounts are split among three areas: FEMA’s Public Assistance programs and disaster recovery and mitigation grants, both from HUD, known as CDBG-DR and CDBG-DR MIT.

Puerto Rico has spent $333 million of the $9.7 billion allocated from CDBG-DR funds, or 3%, according to HUD data through the end of July. None of the $8.2 billion of HUD’s mitigation funding has been spent.

Section 428 of the Stafford Act still hindering

After three and a half years of dealing with COR3 and FEMA, Lornna Soto Villanueva, New Progressive Party mayor of Canóvanas announced in May her first project using recovery funds: improvements to the Cubuy neighborhood basketball court. FEMA obligated $586,000 for this project.

Canóvanas Mayor Lornna Soto Villanueva, at the basketball court in the Cubuy neighborhood. Photo by Vanessa Colón Almenas | Center for Investigative Journalism

There was applause. However, Soto Villanueva raised a red flag. Proposals to begin work on other Canóvanas projects exceeds FEMA-approved funding for her municipality, she said. More than two projects in Canóvanas exceeded the awarded costs, one of them, by $500,000. Spiking prices in the cost of construction materials and FEMA’s delay in awarding projects affected current construction costs, she explained.

Guaynabo Mayor Angel Pérez Otero pointed out that materials such as wood and rebar increased between 25% and 30% in the market. A five-eighths-inch slotted wood panel that used to cost between $16 and $17 is now at $59, the Jayuya municipal official said.

Funds for major permanent works in Puerto Rico — costing more than $123,100 — are authorized by sections 406 and 428 of the Stafford Act. Under 406, known as the traditional method, FEMA allocates money based on actual costs, while under 428 it allocates money based on fixed cost estimates.

Critical facilities are those that provide electricity, water, wastewater treatment, sewerage, communications, education, emergency medical care, and emergency services.

Section 428 states that if costs increase after estimates are approved, municipal governments are responsible for the extra expenses incurred. In those cases, FEMA will not disburse additional funds.

Soto Villanueva said FEMA should recognize the actual construction costs and not the estimated fixed costs awarded. “Projects under 428 should be changed to 406,” she stressed.

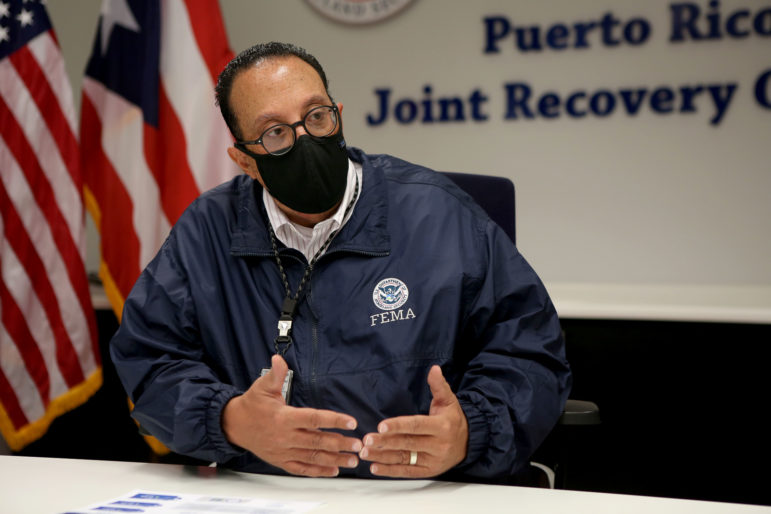

The Federal Disaster Recovery Coordinator for Puerto Rico, José Baquero Tirado, told the CPI he is aware of the situation. He asked the mayors to show him the cases with increases. “I haven’t seen a significant case yet,” he said.

Federal Disaster Recovery Coordinator for Puerto Rico, José Baquero Tirado. Photo by Gabriel López Albarrán | Center for Investigative Journalism

FEMA’s delay in damage inspections, changes, or staff shortage in COR3 and FEMA, and confusion over federal processes delayed the development of permanent work projects after María, as five mayors told the CPI in separate interviews. This was compounded by austerity measures imposed by the Fiscal Control Board, the effect of the earthquakes in early January 2020, in the South, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

A project using Section 406 funds will be built based on its pre-disaster usage and occupancy capacity. And, while a facility under 428 can be built to its pre-existing condition, the funds can be used for improved projects, alternate projects, or a combination of both.

Salinas, a coastal town in the South, opted for section 428 for all its projects, except those that were in historic areas and the culverts (or projects that allow drainages, such as small bridges, access to communities and the fishing docks), said Arlene Figueroa Díaz, director of reconstruction projects there.

Arlene Figueroa Díaz, director of reconstruction projects in Salinas, with town Mayor Karilyn Bonilla Colón. Photo by Gabriel López Albarrán | Center for Investigative Journalism

“It’s due to the flexibility. They told us it would be faster [via 428],” said Salinas Mayor Karilyn Bonilla Colón. The decision was made after an orientation provided by COR3 and FEMA staff in 2019.

Projects under 428 can be consolidated, and funds can be transferred among them, the COR3 director told the CPI. Under this modality, if there is money left over after the project is completed, the municipalities don’t have to return it to FEMA. They can use it in other activities, such as implementing mitigation measures, paying insurance policies and salaries of authorized personnel.

However, Figueroa Díaz explained that FEMA is reclassifying some Salinas projects as small (less than $123,100). “It’s pulling them from the [Section] 428 funding pool,” which reduces the chances of transferring money among those projects.

In 2017, the federal government established that all projects in Puerto Rico costing more than $123,100 would be developed under the alternative procedures of Section 428. However, in January of last year, FEMA announced that it was optional in large projects that were not critical.

Mayors had until March 6, 2020, to choose which section they would use in the projects they had not yet submitted. Three weeks ago, COR3 Executive Director Laboy Rivera offered an orientation session to mayors on the advantages and disadvantages of sections 428 and 406. The new deadline for submitting projects is Dec. 31, 2021.

“A lot of misinformation about 428 was cleared up,” said Baquero Tirado, who participated in the orientation also open to heads of government agencies and representatives of nonprofit organizations.

The mayor of Canóvanas said she is sticking to her decision to change [Section] 428 projects to 406.

“The reality is that projects that are already obligated are already obligated by 406 or 428,” said Baquero Tirado. There are mayors who want to keep their projects under 428. Jayuya and Villalba are two of them.

It is yet unclear what will happen to those projects that are not obligated by the end of this year, whether they will be managed under 406 or 428, Baquero Tirado said.

The snake or the anaconda?

To approve funds, FEMA has what is known as a 19-step project formulation process. In summary, the damages are identified, the scope of work is developed, and the costs are estimated, then funds are approved. In several interviews with the CPI, the mayors refer to this process as the “snake,” since the design of its graphic looks like one.

To disburse the funds, COR3 had an eight-stage process that could take an average of 240 days (to complete). In July of this year, it was reduced to four stages, with an average of 60 days.

Guaynabo Mayor Ángel Pérez Otero. Courtesy photo.

The two processes “are scary anacondas,” the mayor of Guaynabo told the CPI.

His comment is a sample of the federal bureaucracy that they have had to deal with to seek monetary allocations.

“Before, documents had to be submitted through one computer program to FEMA and, in another, to COR3, because the systems did not communicate [with each other]. That represented a major delay. How’s it possible that they bought two different systems?” said Pérez Otero. This situation took more than a year to resolve.

“There were a lot of turnovers. There was a group of people who were there for two or three months and then a new group from FEMA would come. It meant starting over,” the Guaynabo mayor said.

Currently, FEMA has 1,008 employees to work with the María and earthquakes efforts. COR3 has 196 employees, the executive director told the CPI.

In addition, the process was delayed because FEMA wanted proof that the damage was caused by the hurricanes and not due to lack of maintenance. Some agencies had documentation; others didn’t because they had lost it during the hurricane or because in fact, they did not provide maintenance, Laboy said.

Pérez Otero, who chairs the Mayors Federation, said he told FEMA that “unfortunately” they could not provide maintenance reports because “that doesn’t happen in the government. It’s very rare that it happens.”

FEMA warned the government and mayors that “they would give the money, but the structure has to be insured. They cannot decide not to insure it from now on, because FEMA won’t cover [in a future disaster],” Pérez Otero admitted.

2019 deal: Welcomed two years ago, rejected now

Since November 2017, FEMA had to review and approve each petition before COR3 made the disbursement. As head of COR3 in 2019, Marrero announced an agreement between FEMA and the government of Puerto Rico that included the elimination of the manual reimbursement process.

The agreement, signed on April 1, 2019, removed those restrictions. Marrero said — at the time — that it was expected to speed up disbursements from 60 days to 21 days. COR3 was in charge of the review and approval of disbursements and advances as long as it complied with federal regulations, but between the end of July and October 2019, FEMA reimposed the manual process in the context of the Summer 2019 events.

The agreement included “new restrictions,” because to get reimbursements, 100% validation that the work had been completed and the evaluation of compliance would be required, cash advances would be limited to minimal amounts, and an audit process would be implemented.

Now, two years later, Laboy asked FEMA to eliminate that agreement. According to Laboy, the average before was 240 days for disbursements. Although COR3 has adjusted streamline disbursements and advances, the mayors are on a crusade to amend or eliminate the requirements that still hinder the process.

Federal Coordinator Baquero Tirado told the CPI that the decision will be made after receiving the results of a 2019 audit that he hopes will be ready this month.

Vanessa Colón Almenas is a corps member of Report For America.

8 septiembre, 2022 LEER MAS