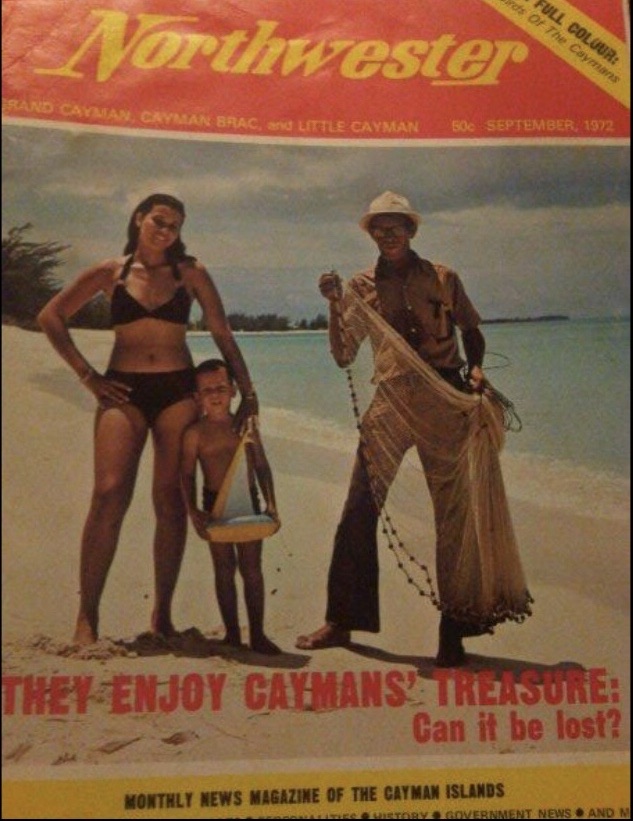

The Beach Club Colony days were a different era for Cayman. In 1970, the Cayman Islands had just over 9,100 residents and many of those, in particular young men, spent their time at sea, working ships with the National Bulk Carriers, a multinational shipping company. The financial services industry was in its nascent days, as was tourism.

In 1968, a stay at the Beach Club would have cost between US $10.50 and US $15.50 a night — a rate that included two meals a day. The 36-room resort was among Seven Mile Beach’s earliest accommodations, alongside the Coral Caymanian, Galleon Beach Hotel and La Fontaine, all since redeveloped.

By 1978, the Beach Club had expanded to 60 units, and laid claim to 700-feet of sandy beach with “the clearest waters in the world.”

Photo by National Archive UK

When the resort reopened in 2005, following a 15-month closure after Hurricane Ivan tore off the second floor, the Caymanian Compass newspaper [now Cayman Compass] described the event as a sort of “coming home” for returning guests.

“At least one well-traveled, upmarket guest … breathed a sigh of relief as he entered the familiar, quaint surroundings, explaining that it was like returning home and he had never discovered anything quite like [it],” the newspaper reported.

Built for tourists, the hotel was also a hangout for locals, a place where Caymanians and visitors gathered to share drinks and listen to music on the beach.

Like most places in that era, Caymanians were welcomed, says Shirley Roulstone, a local tour operator turned activist with the ‘Rascals’ movement — an informal group of Caymanians who first came together to challenge now-defunct plans to dredge and redevelop George Town Harbor into a “mega” cruise ship port.

Roulstone grew up in the 60s and 70s around the old Seaview Hotel, a family operation on South Church Street where she would dive for coins in the saltwater pool. The act entertained guests and gave Roulstone some pocket change.

She’s remained in tourism much of her life, most recently as operator of Cayman Routes Island Tours.

“I’m particularly proud to show our island off and to give people a background of Cayman the way we’ve always known it to be because the newcomers only see what we have now, which is basically a concrete jungle,” she says. “We’re losing our off-the-beaten-path places that make us unique, that make us desirable to visit, and it’s causing a lot of stress for Caymanians.”

Growing up, few places were off limits to Roulstone and her friends and ‘no trespassing’ signs were rare. This was a time guided by the concept of “Caymankind” – although the term, an invention of the Department of Tourism, would not become popularized in the local vocabulary until much later.

“Caymankind” captures a unique local ethos, a community spirit guided by kindness and charity, explains Eden Hurlston, a local musician and also a “Rascal”.

It was a time, lionized in local memory, when neighbors checked in on each other, shared resources and helped keep an eye on the kids.

“With Caymankind, we look at what we have around and we have plenty,” Hurlston says. “We’ve got a little bit of food here. We’ve got a breeze, the children are laughing and running around. We’re wealthy.”

In many ways, the islands remain the same welcoming, “Caymankind” community. It’s a place where finding emergency donations for a family in need or baby supplies for expectant parents can be as easy as messaging a local chat group.

Photo by National Archive UK

But Cayman itself has changed in many ways since the Beach Club days, when one property flowed into the next and frequently neighbors shared a common yard.

Now, places like Seven Mile Beach are dotted with private property signs, restricting locals to remain only in the public area, below the ever-changing high-water mark — the maximum point reached by the sea at high tide. Pair rising sea levels with large, environmentally ill-advised structures were built too close to the sea and that leaves increasingly less of Cayman’s most iconic beach for the public.

There is an evident frustration growing among generational Caymanians, many of whom see their islands building not for them but for foreign investors and private interests. The discontent can be seen in increasingly heated social media debates and listless stares at checkout counters.

“Our people now are stressed to the point of where we can’t give that Caymankind anymore. I mean, we’re talking about opening to tourism, but what am I going to bring them back to?” Hurlstone says. “We just don’t feel at home in our own land. Sometimes I don’t feel at home in my own skin because of the anxiety.”

Twenty years ago, Hurlston returned home to Cayman after a period living abroad, a common ‘rite of passage’ for young Caymanians who often leave the island to study or work. At that time, he felt the few thousand dollars he had saved in Hawaii would be enough to get him started towards owning a home and establishing a family. He was right. He now has a wife, a six-year-old son and a home in West Bay.

“It was very clear to me [in 2001] that that was possible and doable,” Hurlston said. “And now I look at my son and there’s not even a chance of it. It’s ridiculously out of reach.”

The investigations were possible in part with the support of Para la Naturaleza, Open Society Foundations and Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (FOKAL).

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.