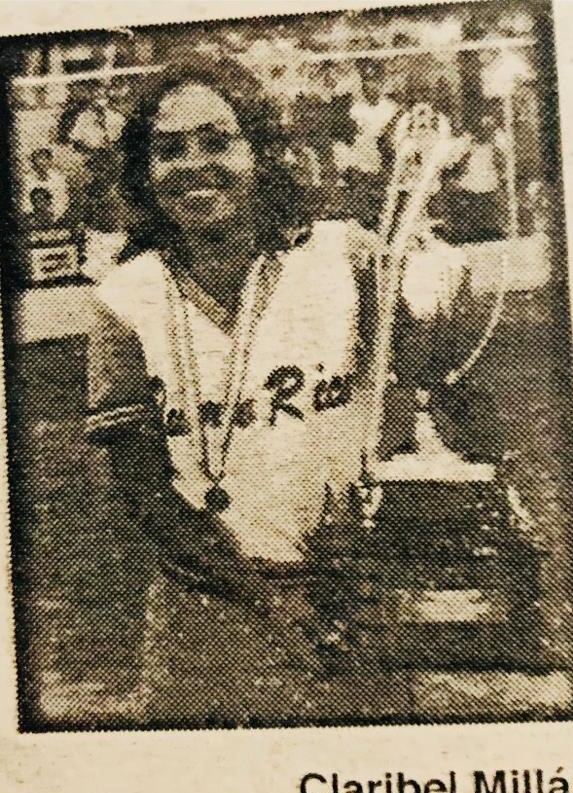

Claribel Millán played with the Puerto Rico National Softball Team during the 1970s and represented the island in the 1974 World Cup held in Connecticut. Her dedication to her national colors was in constant friction with what she says she was discriminated for — being a lesbian. She remembers that the federation leaders and directors of the sport that she practiced asked the players not to speak of or show any type of affection that would bring out their sexual orientation as lesbians. It was the beginning of the so-called golden age of women’s softball in Puerto Rico, when the National Team was directed by Alejandro “Junior” Cruz.

“They called us to a meeting to talk about lesbianism. They were very strict about that,” Millán told the Gender Investigative Unit, a partnership by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) and Todas.

“They removed me three weeks before [the 1979 Pan American Games team] and I was the catcher for Betty [Segarra] and Ivelisse [Echevarría]. How can you be excluded for being a lesbian? In my time, most of us were lesbians,” said the former player.

In 1977, Cruz was boicotted for his comments that lesbian players “were destroying Puerto Rico’s sports teams and should be controlled or eliminated,” according to historian Delia Lizardi Ortiz in her article “New gender relations in Puerto Rican sports.”

Forty-three years have passed since the Pan American Games were held in 1979 in San Juan. The issues of gender perspective and respect for sexual diversity have gained ground in Puerto Rico’s public discussion. Yet comments and threats, like those made by Cruz several decades ago, are prevalent in the sport of softball.

“I don’t believe in that lifestyle, but you can do what you want as long as it is outside the team,” were the expressions made recently by the head of the Jerezanas women softball team at the University of Puerto Rico’s Río Piedras campus, Jorge David Santos, regarding the policy of silence about the sexual orientation of the players, as recent players confirmed to the Unit.

“Relationships are only allowed if they are between male coaches and female players, but couples comprising female players is a problem,” said a source who was on that Jerezanas team.

The UPRRP’s Communications Office denied the information.

“The head of the softball team categorically denies the comments attributed to him by those anonymous sources,” said the institution’s Press Director, Mario Alegre Barrios, who assured that they have not received any complaint about Santos. “No comment of this nature would be consistent with the institutional belief on these issues and with what is established by the Title IX Office. The UPR and our Campus have institutional regulations to deal with situations of this nature once it is formally known, (through the corresponding channels), and according to the applicable regulations,” he added.

A former player who represented Puerto Rico and competed in the 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics, Eiffel Lebrón Ortiz, confirmed that discrimination against lesbian players lives on in softball, particularly from the heads of both the Federation and the National Team, which Santos currently directs.

“Yes, they still discriminate against us. I’m telling you because I’m a lesbian and I’ve been married to my wife for five years and she’s also a player for the National Softball Team,” said Lebrón Ortiz.

Santos is also a Christian pastor at a church in Trujillo Alto, according to his Facebook page. He also works for the municipality as Director of the Department of Sports and Recreation. Multiple calls to Santos’ office at City Hall went unanswered.

“I’ve never had problems with him [Santos], but I do know that he doesn’t want the National Team to have lesbian players, and now that he’s the head of the National Team, as you can imagine, we’re going to take 10 steps back. The UPR isn’t going to go against its coach, but we all know that he doesn’t agree with it,” the 40-year-old athlete, who currently competes in Class A men’s baseball circuit, said about the national and UPR coach.

The Puerto Rico Softball Federation did not respond to emails, calls, and messages to the institutional WhatsApp account.

“We are already in our 40s, but what will become of the new generations? They’re the ones I worry about,” she added.

The so-called “law of silence” is a form of psychological violence. This is established in the Puerto Rico Department of Sports and Recreation’s “Guide for the Prevention and Intervention in situations of Violence and Harassment in Sports Contexts for Sports Clubs and Entities.“ It’s one of the five forms of bullying and harassment recognized in the 2016 International Olympic Committee Memorandum of Understanding. The other four forms are: sexual abuse, sexual harassment, negligence, and physical abuse.

At the mercy of impunity and the absence of protocols

Of 15 former volleyball or softball athletes who responded to a questionnaire created by the Gender Investigative Unit on Harassment in Sports, four stated they had experienced some type of harassment in their sports experience. Of this group, three said they had suffered psychological abuse and one said she experienced “sexual comments from a teacher watching her practice.”

Among the 15 participants, nine expressed direct knowledge of cases of harassment. Of these nine cases, six are related to the organization to which the athlete or former athlete belongs. In most of these cases, the harasser was the coach. When all were asked if they believed there are adequate protocols for handling sexual harassment cases in Puerto Rican sports, 14 confirmed not knowing the protocols and one stated there are no adequate protocols. They all agreed on the need for accessibility to the information related to case management protocols for people associated with sports and to the public.

In what ways have you witnessed sexual harassment occur in sport?, the players were asked through the questionnaire. Some answers were: “That they get very close, or they touch you.” “They shout expletives with sexual connotations from the bleachers or around the fields and parks.” “Some coaches make inappropriate comments or give strange looks.” “The way they touch you with the excuse of helping you position yourself or improve your position.” “A sudden closeness and the obvious glances toward the private parts.” “Verbal harassment.” “Unwanted approaches by the coaches or the fans.” “Threat of being fired in when not allowing that type of proximity.”

In Puerto Rico, volleyball is widely practiced by women at the club level. The National Volleyball Team has been successful and participated in the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. Meanwhile, women’s softball has an important history, which includes the participation of the National Team in an Olympics (Atlanta 1996), as well as multiple successes and medals in regional tournaments such as the Central American and Caribbean Games, as well as the Pan American Games. Puerto Rico currently ranks number five among all women’s softball national teams worldwide.

Attorney and current player of the National Women’s Superior Basketball League, Michelle González believes that although the leagues and federations should not bear all the responsibility when cases of harassment and sexual violence occur in sports, there should be strictness with people who are hired or recruited to lead teams of children and youth. Likewise, the athlete advocated ending the cover-up policy in the leagues and federations.

“The first protocol they must follow is to prevent harassment. That is the first protocol that must exist, prevent it. And how can these things happen? Each of the leagues offers a workshop, and does not allow the ‘secret’ relationships [between the manager and the players]. I had a meeting with my coaches, and I told them ‘None of you are going to talk privately with any player. I don’t care if you’re a male coach or a female coach. You aren’t going to talk alone with any player,’ and these are protocols that the league and the teams must implement to prevent,” said the also former member of the Puerto Rico National Team that participated in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

“The second protocol that must be implemented is, if it happens, what are we going to do? This ‘ay bendito’ behavior is already a social behavior. You may have to ask the president of the league, how can you possibly prefer to cover up an act like this and protect a coach, than to protect a minor or to protect a woman or to protect a child?” the attorney questioned.

One of the main researchers about harassment in Puerto Rican sports is Dr. Enid Rodríguez from the Center for the Application and Study of Sports Psychology at the UPR in Mayagüez. Among the findings of her studies, the academic specialist in sports psychology explains that there is a great mistrust of athletes about how leagues and federations handle complaints related to cases of harassment in sport. That aspect, according to her, causes many athletes not to make a complaint when they are harassed or assaulted by coaches or other figures of power in the sport.

“When we carry out the investigations at the university, those we interviewed, they tell us ‘I reported it, I processed a complaint,’ and when we asked the federation, they told us that there was nothing. That’s why the athlete says, ‘this is a mafia,’ because no matter what you report, nothing is going to happen. The federation doesn’t acknowledge it [the reported case] because it doesn’t have a protocol,” Rodríguez explained.

The educator from the UPR in Mayagüez explained that research at the international level shows the trend that gender discrimination, harassment and sexual violence are more common in those sports traditionally practiced by men or that are “male-oriented,” but that are also practiced by women. Within that group are softball, boxing, basketball, judo, taekwondo, and baseball, among others.

Photo by José Reyes | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

In the case of volleyball, although it is a sport widely practiced by women and is culturally perceived as in harmony with the ideals of “femininity,” Puerto Rican professional players have denounced the common practice of sports leaders who make comments and suggestive looks that defile them. “Casual approaches” from coaches to players are also common, according to what well-known volleyball player Karina Ocasio told the Gender Investigative Unit.

Photo by José Reyes | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Although harassment and sexual assaults, including those that occur in sports, are prosecutable through the Puerto Rico Penal Code, Rodríguez believes that if the leagues and federations lack protocols, it will be tougher to solve these cases and earn the trust of the athletes in the institutions that govern their sports practice.

“If [the complaint] by athletes in Puerto Rico isn’t processed by the sport, they don’t go [to the Police]. If I’m an athlete and I go to the police, they will send me to sex crimes (department) to process it. So, it isn’t that they’re going to put me in another team, it’s not that they’re going to put me in another [sports] club. And since the athlete knows that life in sports is short, they grin and bear it,” said the researcher.

“The Police doesn’t have a record of whether sexual violence by a coach or a team parent even took place. It’s just sexual violence, sexual harassment, and it was processed as any other case. The Police themselves don’t have that information because they do the same thing (as the sport). It’s impossible to identify it,” Rodríguez added.

“When I talked about it and asked the Police for the data, they explained that as it appeared in the report it was a case of sexual violence, Aguadilla area, community x. Where was it? A recreational park: but it doesn’t include or identify that complaint whether it was someone in sports, if it was an athlete, if it was a coach, if it was a parent of a child. They told me that they don’t have that information, that they have it in a general way. Reports can be made of what happens in recreational areas, but not all that are for recreational areas correspond to athletes,” Rodríguez explained.

The UPR doesn’t go the extra mile

At the university level, sport is governed by the Interuniversity Athletic League (LAI, in Spanish), which has a protocol known as the “The Interuniversity Athletic League of Puerto Rico’s Policy to establish the protocol for the prevention, intervention, and follow-up of harassment, sexual harassment and intimidation cases.” As part of prevention, the LAI document establishes that workshops will be offered at the start of each academic year on the topics of bullying, harassment, and intimidation. Regarding cases of bullying and harassment, the victim must inform the institution so that they can “proceed with an investigation of the allegations,” and if necessary, proceed “with the formulation of corresponding charges.” Likewise, “the Commissioner’s Office [of the LAI] may take precautionary action against any of the parties pending the conclusion of the disciplinary process at the university.”

The Gender Investigative Unit asked the LAI Commissioner Jorge Sosa if the victim athletes really trust in delegating the investigations to the universities, when many times those who harass are people hired by the educational institution’s athletic departments.

“That was the subject of discussion in the Governing Board [of the LAI] because the universities must have regulations in order to receive the funds under Title IX. My wish was that we [in the LAI] had a regulation at the sports level, but the universities made the point that they already had that regulation and basically the regulation is modified so that, if the complaint reaches us, we channel it, as it says here [in the LAI document] and the case is referred,” Sosa explained. The LAI did not answer how many cases they have referred in the past 10 years.

Those universities that receive federal funds must comply with Title IX regulations, which is a federal statute created in 1972 to prohibit discrimination based on sex in educational institutions. Within the modalities of discrimination stipulated by Title IX, situations related to gender violence, stalking and sexual harassment are included.

In the case of the UPR, the 11 campuses and the Central Administration have Title IX compliance officers, as required by law.

But although the Title IX program recommends establishing a secondary coordinating committee, recognizing these problems in sports, the UPR does not give an emphasis to the problem of harassment in university sports, but rather it is addressed as a generic issue that is monitored along with the rest of the cases of violence and discrimination that come up in different university offices.

“We don’t have a [gender affairs] committee specifically in sports. [The Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee] exists to deal with all matters that have to do with gender equality, and I believe that the issue of sports would also be addressed,” said the UPR’s coordinator of Title IX and Central Administration compliance, Yarima González Crespo.

The units don’t have a Title IX coordinator specialized in sports, although the law recommends it. “The position does not exist,” González Crespo confirmed.

A person who alleges to have been a victim of sexual harassment may take their complaint to the Title IX Coordinator, who must initiate the investigation and summon the parties involved. The process includes reviewing factual, date and location information. In addition, the parties have the right to an advisor to accompany them during the process. The UPR explains that the complaint proceeds only if “the Appointing Authority or its authorized representative reports the formulation of charges against the Defendant, after having carried out an investigation of the alleged facts.“

Trabanco and the Volleyball Federation don’t want to talk about the harassment

Last January, a judge decided a case against former volleyball coach Juan Hernández Lozano for sexual abuse, in violation of Law 246 for the Safety, Protection and Welfare of Minors. The man, who was 55 years old at the time, was charged with lewd acts by sending sexually-oriented text messages to a 15-year-old girl. The events occurred while he was a coach at an undisclosed private school and was out on bail and forced to wear an ankle monitor on similar charges.

As a school employee, the Puerto Rican Volleyball Federation (FPV) does not oversee his work. Schools, private schools, and universities are not affiliated with Puerto Rican volleyball’s main governing body, making it impossible to have a uniform policy for handling cases of harassment for all the institutions in which the sport is practiced in Puerto Rico.

Volleyball player Karina Ocasio said about this coach that “he’s just as guilty as the people who continue to give him the opportunity to work around children.”

“Many times, they cover things up among themselves, because of the years they have been working together or, so they aren’t embarrassed by the [sports] club,” said the athlete, who currently plays with the Criollas de Caguas in the LVSF.

Photo by José Reyes | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

All clubs, leagues and tournaments affiliated with the FPV must comply with Federation regulations. The Gender Investigative Unit did not find any section or protocol related to the handling of harassment cases in the regulations published for the main tournaments and leagues sponsored by the FPV. Trainers are only required to fill out an Act 300 Certification Application, also known as the “Puerto Rico Child and Elder Care Providers Criminal History Verification Act.”

The Investigative Unit called the FPV’s office several times to request an interview with its president, César Trabanco, but the efforts were unsuccessful. In one of the calls, the person who answered said “the President will not make any more comments on this issue [on harassment].” When trying to reach the FPV offices, the secretary said Trabanco was in his office in Ponce and reiterated that he would not make public statements on the matter.

Photo by José Reyes | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

How do you think sexual harassment in Puerto Rican sports should be dealt with? the players were asked in the questionnaire. “Specific sanctions within the federations.” “Publishing or a registry of aggressor coaches and referees.” “As soon as someone expresses feeling uncomfortable, they should start looking into the matter. If it is about sexual harassment, they should remove the coach immediately while they do the investigation.” “Efficient and on time.” “First, I believe that women must be well oriented on the subject, because on many occasions inappropriate behaviors are accepted for fear of losing a position in the team.” “Confidentially and safely toward the victim.” “That communication is paramount, where there are supervisors in whom one can trust and rights are asserted,” were some of the responses.

“The mere fact that it isn’t [in the regulations], gives freedom to [harass] because there’s no way to admonish. So, I think that it’s something that should be added to the regulations of any league, of any sport, of any institution, because this is something that happens. By not having it there, there’s no longer any fear, because there are no regulations for that or no sanctions,” said Ocasio, who also represented Puerto Rico in an Olympics and in several regional events.

Violence on the courts and stadiums is not limited to the acts that some coaches can commit toward players or minors. At times, the harassment can come from federation chiefs, table officials and even the public that attend sporting events. In a sport like volleyball, it is common for men attending women’s matches to shout sexual comments at the female players.

“The fan thinks that when they buy a ticket to go to a match, that ticket gives them benefits and powers to express themselves how they see fit. Sometimes they are disrespectful,” said former LVSF and beach circuit volleyball player Yarleen Santiago.

“I dedicated my final years to beach volleyball in which the uniform is a little different. The woman’s body is much more exposed. It’s a delicate subject, since you’re playing on a beach wearing a bikini and you must be very mature to be able to deal with that type of comment or experiences. From my perspective, maturity as a woman was what helped me deal with this type of situation,” said Santiago, who in 2011 won a bronze medal for Puerto Rico at the Pan American Games held in Guadalajara, Mexico.

“This type of behavior is normalized and when you see it as something normal, the reality is that there’s no type of intervention because they don’t see the seriousness of the matter,” lamented Santiago.

Challenges for sports psychology

The recurrence of cases of harassment and violence in sports causes athletes to seek the services of psychology professionals. Sports psychologist Mercedes Rivera Morales said that when intervening with athletes victims of harassment, it is common to discover that sports organizations incur in the practice of believing the coach rather than validating the victim’s testimony.

“It’s a violent act that goes against that person’s dignity. The mere touch, a look, or an innuendo, all that hurts and will influence self-esteem. The effect on gender-based violence victims is that they question whether the sport is still worth playing. Many times, they re-victimize themselves, they think that they provoked it. It can become a trauma and you must be with them, you must address, you must support her, so that she sees that she’s the victim, that she doesn’t deserve that, that she isn’t to blame, that she has her rights and that her situation must be addressed,” Rivera Morales said.

This type of case merits integrating approaches with a gender perspective to the study of sports psychology, Angely Hernández, doctoral candidate in psychology and researcher on gender and sports issues, said.

“Sports psychology programs must include a gender perspective. Discrimination, sexism, oppression, and marginalization are still observed within sports. For the most part, discrimination is directed toward women and trans people in sports. This problem is systemic and to begin to dismantle it we must look at the regulations of sports bodies and laws that perpetuate inequality toward these populations. I believe this is possible through an approach with a gender perspective,” said Hernández.

Dominance of male perspective makes it difficult to address cases

In September 2021, the Puerto Rico Olympic Committee (Copur, in Spanish) appointed a Special Regulations Review Commission. The group was composed of former softball player Ivelisse Echevarría, basketball player and attorney Michelle González, and labor lawyer Jaime Sanabria. One of the Commission’s goals was to temper the regulations of the federations affiliated with Copur to the Olympic Charter and issues related to gender equity. Weeks earlier, a controversy arose at the FPV level, after the LVSF regulations did not allow the Sanjuaneras de la Capital team to substitute, in the middle of the final series, its imported player, Destinee Hooker-Washington, who was pregnant.

“This [the Commission’s appointment] is directly linked to the volleyball case of the pregnant player who asked to leave the tournament,” Copur president Sara Rosario explained.

“In terms of the issue of harassment and violence in sports as such, there are some suggestions [to the regulations], especially in creating the safe environments that are required for women in sports. An issue of harassment, gender violence, it isn’t easy for the victim to make it public. What we want is to provoke that it is talked about, that it is discussed, that we don’t take it for granted. Inclusion is important in sports, but there must be clear and specific measures in each of the federations’ regulations. And these recommendations are aimed at that, in that in a specified period of time, the federations can have clear and specific ways of how it will be handled,” Rosario said.

The CPI asked Rosario what the appropriate term of time for the federations is to handle these cases, but the President of the Copur only said “it will be up to each federation to establish the term and the procedure in its regulations, understanding that it is a matter of high priority.”

Of the five active teams in the 2022 LVSF season, only one has a woman in the role of owner. In the case of the 35 sports federations affiliated with Copur, only three are chaired by women. Rosario believes this gender inequity in top managerial positions in sports must change so that more women participate in decision-making that affects female athletes and that has an impact on their needs as athletes.

“It’s a deficiency that we always have in sports, which has been dominated mostly by the male gender. It’s difficult for us women to get there, to make ourselves viable. Not all, since there are many general tasks, many who are treasurers and many who sit on the board of directors. But they don’t necessarily accept the challenge of directing. They think it’s still a bit manly, that they don’t have the time for obligations at home and so on,” Rosario said.

“In softball almost all the owners have been men. While we don’t have women in these chairs of power and decision-making, these [gender] issues are really going to continue to be somewhat relegated to the agenda,” added the Copur president.

Meanwhile, Dr. Rodríguez from the UPR in Mayagüez disagreed. She said the problem is not merely that women don’t want to make themselves available or accept the challenge of running federations.

“I don’t think that’s the reason. It’s a very sexist argument. It’s justifying that this doesn’t happen. To take on the presidency of a federation you must have the approval of a group of people who are going to vote for you and most of this group of people are men. The people in the federations are there for 20 years, they rotate the positions. There is no opportunity to enter with another view. If you aren’t endorsed by someone from the same federation, nothing will happen,” Rodríguez said.

Former softball player Lebrón said the regulations of her sport in Puerto Rico are not updated and do not respond to the needs of the women who practice it. She also criticized that in a sport in which women have given Puerto Rico so many victories, there are no women heading the teams or in the leadership of the National Team.

“It isn’t so important for them to set a harassment rule, specifically because everyone in the [Softball] Federation are men. In addition to harassment, there’s a bit of machismo in the Federation because there are no women, there are no female leaders. The last female coach that the National Team had was when I was there, and it was until 1996. After that, there have been no more women coaches. So many good players that Puerto Rico has produced…and there isn’t a woman coach,” Lebrón said.

For her part, the only female owner in the LVSF, Lilibeth Rojas, said although she believes that women should have a more active role in sports decision-making, “we cannot wait for that to happen [more women in positions of leadership] to act. We must work with this right now.” The former volleyball player advocates that there be more guidance and information available to children, parents, and young athletes, as well as coaches, so that they know the limits of their profession.

“Perhaps [women] have a slightly clearer idea of certain things and we can include them in the regulations. I think that the most important thing here is guiding the children and the coaches,” said the representative of Las Pinkin de Corozal.

Regarding where the protocol documents for handling these cases should be available, the players mentioned in the questionnaire: “Entrances, canteens and bathrooms of sports facilities.” “Web pages of federations and tournaments endorsed by the federations. “In every club, school, league that plays a sport.” “It must be included in the documents that anyone signs to be part of the team that includes all the information starting from how each thing is cataloged and steps to follow when someone has gone through the same thing.” “Online, in contracts and regulations.” “On desks, in the offices of coaches, school principals, teachers, and handed out to parents and players at meetings.”

If you or someone you know has been a victim of sexual violence, you have the right to seek help. You can call the Orientation and Help Line Against Sexual Violence (LOA, in Spanish), at 787-337-3737, or the Help Center for Rape Victims, at 787-765-2285, the Ombudswoman’s Office, at 787-722-2977, or 939 CONTIGO (266-8446) emergency and help line.

Rafael René Díaz Torres is a member of Report for America.