“Searching for a house in Puerto Rico is mission impossible.” That is how pediatrician Cynthia Miguel summed up her experience trying to find a property to live with her three children in San Juan.

“I saw about 10 properties in San Juan, seven or eight walk ups and apartments. I ran into waiting lists of up to 15 people to see them. I had realtors who told me they would call me to let me know when they could show me the property. I never got any calls back,” she recounted.

The doctor ultimately gave up her idea of renting in San Juan and found a house in Trujillo Alto, a town 10 miles southeast of San Juan, that implied a 25% increase in her rental costs, more hours on the road, and more expenses in extended childcare due to the change of location.

Like this mother of three, thousands of Puerto Ricans have been affected by the housing shortage caused by the disruption in the real estate market in Puerto Rico.

Cynthia Miguel, pediatrician, and mother of three

“I lost count of the places I called; there were like 12, but none were successful.”

The increase in foreign capital due to the promotion of the Puerto Rican archipelago as a tax haven, the proliferation of short-term rentals, a halt in the construction of low-income housing in the past decade, as well as the remote-work flexibility prompted by COVID-19, created the perfect storm for the average price of properties for sale to increase 63% between 2012 and 2021, an investigation by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) revealed.

The combination of all these circumstances has caused a shortage of available homes, for purchase or rent, for the working class and for the island’s most vulnerable residents in areas where work activity and citizen services are available or where Puerto Rico’s natural attractions are enjoyed, according to interviewed experts. The government estimates that the current housing deficit in Puerto Rico is 20,000 units.

The wave of purchases, increases in prices and displacement began in luxury enclaves in the areas of Dorado, in the North coast, Rincón, in the West, and San Juan, but has spread to other areas of these same towns and to poorer municipalities, mainly on the coasts, according to sales data analyzed for this investigation and interviews with real estate brokers.

This is coupled with a never-before-seen increase in cash property sales in the past 10 years, which has triggered market speculation, according to CPI’s investigation, which analyzed more than 97,000 property sales and interviewed more than a dozen real estate industry experts.

The CPI found that there is no database or information that shows the magnitude of the increase in cash sales in Puerto Rico because the Property Registry does not collect this information; by law the Registry is not required to include this fact in the registration entry that it publishes, the agency acknowledged.

“There may be many cash sales of properties that are not registered in the Property Registry,” Joaquín del Río, the Registry’s administrative director, warned.

However, the CPI was able to compile and analyze a database of the cash sales collected by the most comprehensive purchase and sale information service that exists in Puerto Rico, Tasamax, and identified a 740% growth in the cases registered by this company, when comparing 2012 records of with those of 2021, whose total was 1,884 cash transactions.

Of these purchases, 46% occurred between 2020 and 2021. This database of cash purchases that the CPI compiled is the only one that currently exists for analysis purposes, according to the experts consulted. The private real estate information services do not allow downloading their databases.

At least six real estate experts consulted said the increase in these types of transactions has been enormous, even exceeding 50% in some markets such as Dorado. One of the industry sources, who requested anonymity, said they are aware that most of the properties of $800,000 and up in Puerto Rico have been bought in cash for about three years.

Tasamax told the CPI it cannot estimate the percentage of total cash purchases in their database because they only include cases that they investigate at the request of one of their clients, mostly appraisers, or on their own initiative in markets of high interest for the industry.

In other words, cash sales are much higher than those reflected in the CPI sample. This service is mainly fed by the information that most financial institutions send them and covers around 70% of the market of sold financed properties in Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico’s House of Representatives Speaker, Rafael Hernández Montañez, submitted House Bill 1416 in July, which pursues that all cash purchases and sales submit a copy of the appraisal, title study or measurement plan, new requirements that he said would lend greater transparency to these transactions. Initially, the measure has been met with qualms among notaries and the real estate industry, which say it involves costly red tape.

The sample of cash deals that the CPI compiled is revealing, both in terms of the pace of growth since 2019 and in changes in buyer profiles. Between 2012 and 2021, almost everyone who bought in cash had names and surnames of Hispanic origin, typical from Puerto Rico. As of 2018 — and even stronger since 2020 — the proportion of names and surnames of Anglo-Saxon, Arabic and Asian origin increases.

In the sample there were only 15 sales in cash in 2012, of which only one corresponds to someone with a non-Hispanic name. In 2013, only 6.3% of the 48 cash buyers had this type of name. This trend began to change starting in 2019, and by 2021, a total of 122 of 492 buyers or 24.8% of them had non-Hispanic names. That proportion does not include corporations that are buyers — among which there may be additional foreign owners.

The sample used shows that the towns where the percentage of cash sales increased the most during the past 10 years are Maunabo, in the eastern coast, Naranjito in the central mountainous region, Ceiba and Humacao, both in the eastern coast. Maunabo and Naranjito are small markets where the increases were focused in a single housing project and in the sale of individual lots with structures, respectively.

A doctor in Maunabo, whom we will call José to protect his identity, was one of the cash buyers of an apartment in the Villas del Faro complex in that municipality. He bought the property in 2021 given its low price at the time.

The doctor said the complex, which is more than 20 years old, did not go bankrupt, but several of the apartments were repossessed by banks and were sold at very competitive prices. In his case, the purchase was with another individual and did not exceed $140,000, although he said he had seen offers of around $60,000.

“Here [in the complex] there are many foreigners who have summer apartments. But with those sales of repossessed apartments, most were picked-up by Puerto Ricans, including people from Maunabo itself. In my case, I was able to buy it because I had savings and because that apartment did not have a mortgage,” said José, who noted that the prices that were seen at the time he bought had already skyrocketed.

In the case of Naranjito, the sales ranged between $15,000 and $55,000 and responded to lots with abandoned structures that were sold by private individuals, said Silvia Rodríguez, director of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism for that town.

“We believe they have been sales by people who have gotten rid of their properties,” Rodríguez said, referring to the sales the CPI identified, all in the same sector of Guadiana and whose buyers are mainly people with Hispanic names.

In terms of net sales, the highest number of cash sales were registered in San Juan, Dorado, Guaynabo and Bayamón, all four considered San Juan metropolitan areas.

The findings associated with the general outlook of the real estate market were taken from a database that the CPI analyzed for this investigation that gathers information from several anonymous sources that collect data from the Property Registry, the Municipal Revenues Collection Center (CRIM, in Spanish), and the banking sector.

The information was validated with official data provided to the CPI by the CRIM and by the Office of the Commissioner of Financial Institutions (OCIF, in Spanish), and private information service Tasamax, which draws on agreements with most of the financial institutions that operate in Puerto Rico, from official government sources, real estate brokers and appraisers.

The Property Registry, custodian of all information on property transactions in Puerto Rico, refused to hand over its public information database to the CPI. The agency said that to gain access to this data we could go through the hundreds of thousands of digital files of each transaction in its system one by one.

The result of this investigation is the most extensive analysis that has been made to date of the real estate market in Puerto Rico from 2012 to July 2022.

For many it’s impossible to compete

Nannette Rendón, from real estate consulting company Rendón Financial Group, said the increase in cash sales makes many people want to sell faster and at higher prices, even in areas that were not previously considered to be of high interest for real estate investments.

“There were some niches in the last decade, like Rincón, Isabela, in the northern coast, and Dorado, for example. After the pandemic, the sale of properties for cash has become more widespread, expanding to other areas. Normal people say, ‘since everyone is selling cash, let me list my house for more to see if I sell it [that way]’,” Rendón said.

As median home prices rose sharply, the availability of affordable housing to buy or rent shrank as many owners took their properties off the regular market to sell them for cash at a higher price, at least three real estate brokers and people who sought to buy or rent a home this year said.

“I would go look for a house, maybe the house for me, it was the property for me, but if someone came with the cash, they would give it to them first, they would give priority to that person. And I’ve experienced that many times and they were almost always foreigners,” said Vilmarys Rivera Navarro, who tried to buy a house through the Department of Housing’s (DV) Direct Assistance Program for Buyers, which grants up to $55,000 for the down payment to low- and moderate-income people to buy their first home.

Vilmarys Rivera Navarro, 38-year-old professional

“I feel extremely frustrated. I don’t see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Rendón said there is a clash between the program’s goals and real estate market ads, which increasingly seek cash buyers and reject government subsidies such as the Buyer’s Assistance Program.

Rendón said now there are more “cash only” sales listings for properties in sectors that were previously occupied by middle-class families and that this has affected the inventory because, for example, “a property that someone can sell me, that I qualify for what the house is worth, won’t sell it to me because they’re waiting for a miracle [from a cash buyer]. So, I lose that opportunity. There are many qualified people, and they can’t find a home.”

The real estate specialist said in the last quarter of the year, she has perceived a greater receptivity towards the program although the lack of inventory persists.

Despite the lack of inventory and the bureaucratic banking difficulties it faces, Housing Secretary William Rodríguez said he has his hopes set precisely on the Buyer’s Assistance Program to reduce the need for housing for people of low-to-moderate income who lack the resources to buy a property. As of the first week of December, the program had disbursed 48% of the $295 million available for 4,478 mortgage closings.

Rodríguez warned that it is illegal under Puerto Rico laws and United States laws to discriminate against families seeking housing through vouchers or government programs and urged anyone who feels they have been discriminated against to formally denounce it in the DV.

“We’re going to address each one of these complaints. It is unacceptable,” said Rodriguez. He urged those affected to write to [email protected].

The local population is displaced

The combination of these changes in the property market has accelerated the displacement of the local population to replace it with a new breed of owners who have bought many vacation rental and short-term rental properties, and not necessarily to convert them into their permanent residences or to offer them to the long-term rental market, said half a dozen experts that the CPI consulted.

Miguel Rivera, former Political Science professor at the UPR

“Something that cost $1,200 [to rent] a year and a half ago is now $2,500.”, dijo.

“The trend is that the most marginalized populations are being physically marginalized; they have less and less access to places where jobs are, public services — schools, health services, public spaces for recreation — which have these virtues because they were designed for communities,” said planner David Carrasquillo.

“These areas are precisely the first to become gentrified and limit access to populations with a lot of money that are often the ones that need those places the least,” he added.

There are complaints posted daily on social media by people who cannot find a home to buy or rent, or who must leave the home where they live because they cannot pay the rent increases that the owners impose on them abruptly. There have also been documented cases of tenant evictions ordered by the people or companies that have bought the property to remodel it and rent or sell it at a higher price or for short-term rentals.

However, the government of Puerto Rico does not have a plan to address the problem of affordable housing. Government efforts have been directed primarily at programs for families with low or moderate income, who have also been hit by these changes in Puerto Rico’s housing market. Still, the problem persists for those who want to rent or buy a home, but their income does not allow them to access government subsidies or aid.

In June 2021, DV launched an incentive for landlords to offer their units to the Housing Choice Voucher Program Section 8. The incentive was extended on September 1, 2022.

This is because the disruption in the real estate market also aggravated the shortage of inventory of social interest properties, Carrasquillo stated. The Disaster Recovery Action Plan that the Department of Housing submitted to the US Department of Housing (HUD) to access recovery funds describes the need for affordable housing for disadvantaged sectors in Puerto Rico and gives priority to addressing the problem.

To date, there are 7,723 families waiting for a property under the Section 8 Program for people in need, Public Housing Administrator Alejandro Salgado Colón said.

Ayuda Legal, a nonprofit organization that offers free legal support to disadvantaged people to assert their right to housing, believes this demand for subsidized housing responds to the lack of inventory caused by speculation in the real estate market and non-compliance by Section 8 landlords with federal quality standards to participate in the program.

Secretary Rodríguez announced a plan to buy 1,000 affordable housing units in projects under construction and existing housing for people affected by Hurricane María and the earthquakes of January 2020. In addition, he said the government expects to add another 981 units with six new developments already under construction.

In a second phase, the construction of another 2,535 units is planned in 17 new development projects that have already been selected. Construction of these units will start in 2023, he said.

Act 22, signed by Governor Luis Fortuño in 2012 and consolidated since 2019 with other incentives in the current Act 60, allows, promotes, and encourages the transfer of wealthy people from the United States and other parts of the world to the Puerto Rican archipelago. The move is promoted in exchange for tax incentives, but the government has been ineffective in monitoring whether new residents meet the requirements in exchange for the tax benefit they get, according to prior investigations by the CPI.

There is a public policy of selling Puerto Rico as an investment destination through tax incentives which require very little in return from the beneficiaries of this program, said Iván Zavala Steidel of InRealta Grupo Inmobiliario and CEO of Reality Realty.

“It’s not organic. There’s a concerted government policy to attract these investors. You have Invest Puerto Rico, which was created to promote Puerto Rico as an investment destination, the DMO [Destination Marketing Organization] and promoters who are dedicated to finding them. It is the government and private companies that are dedicated to that,” he said.

The Department of Economic Development and Commerce (DDEC, in Spanish) runs the Resident Investor Program and promotes the relocation of non-resident investors to Puerto Rico with the goal of attracting foreign capital. Since January 1, 2020, when Act 60 went into effect, these investors are required to purchase and establish a primary residence in Puerto Rico within the first two years of the decree’s approval. In exchange, they get 100% exemption from paying taxes and from the capital gains they generate after being Puerto Rico residents.

Experts consulted, such as Attorney and Certified Public Accountant Kenneth Rivera, believe that the effect of this obligation on Act 22 beneficiaries to buy a residential property is still not fully reflected in the real estate market. Most of the 2,751 people who have landed the benefit since 2020, and who still do not have a permanent residence in Puerto Rico, would have to do so before the two-year term expires.

As of July 2022, a total of 4,645 foreigners had obtained decrees under Acts 22 and 60, but the requirement to buy a property has varied over the years. From 2012 to 2014, they did not have to buy a property, but they had to prove that they lived in Puerto Rico at least 183 days a year, so they had to at least rent a home.

The property purchase requirement was imposed in 2015, but in 2017 it was removed again during the governorship of Ricardo Rosselló. In 2019, this obligation was reinstated in Act 60. Compliance was not audited until 2021, when the first decree cancellations began under DDEC Secretary Manuel Cidre.

The result is that since 2020 only 500 beneficiaries have reported to the DDEC having purchased a property. This constitutes 10.7% of the current beneficiaries. The CPI was able to identify a total of 301 transactions made by 276 individuals or corporations with officers whose names match those on the DDEC’s Act 22/60 list of beneficiaries.

Only 34.8% of these transactions were in the mega-luxury or commercial segment of more than $1 million; 18.3% of these purchases by foreign investors were in properties ranging in price from $500,000 to $999,000.

Meanwhile, 46.9% of property purchases by Act 22/60 beneficiaries were in price segments between $25,000 and $499,000, which is the price range of properties sought by Puerto Ricans from the professional and working classes.

“Although the jump in cash sales cannot be accredited to a single effect, Act 22 [Act 60] has definitely had some effects of restricting access to housing,” said planner Carrasquillo.

He said Act 22 is part of a framework of public policies that project Puerto Rico as an investment destination.

The Housing Secretary does not see it that way. Rodríguez ruled out that property purchases by foreign investors have contributed to the current shortage because he is convinced that this group has only affected specific geographic spaces.

“We’ve been seeing that there are specific niches in specific areas where there has been a great investment by the investor sector that comes to Puerto Rico like the people who are investing in Airbnb. Currently, to us that is not the main issue that is affecting the housing inventory. It isn’t,” said the head of Housing.

He believes the shortage of affordable housing is mainly because the construction market has not invested in this kind of projects, and the spike in construction costs due to inflation.

“It is a globalized issue; it’s a global issue after the post-pandemic inflation and cost increases. This coupled with 10 or 12 years of zero construction. These events have definitely limited the inventory,” Rodríguez added.

Meanwhile, the head of the Puerto Rico House, as well as the Puerto Rico Senate President José Luis Dalmau, don’t favor greater regulations on the local real estate market, but rather more oversight so that tax exemption decree requirements are complied with, and the promotion of a greater agility in the disbursement of existing federal funds to boost inventory.

“The government has some funds to create the circumstances and accelerate the process of facilitating those terms. Before there was a problem: there was no money. But that doesn’t exist today because there’s enough federal money to help,” Dalmau said.

Hernández Montañez is in favor of direct assistance programs for people to buy housing. He promotes hybrid housing projects that allow a third of the units to be sold at market value; a third to be sold with public aid or subsidies; and another third that is rented with the option to buy in a reasonable term for the buyer.

Social interest housing shortage worsens

A foreign investor living in Puerto Rico attracted by the Act 22 tax incentives bought a residence in Dorado Beach East for $13 million from a Puerto Rican who had acquired it for $3 million. For both, this transaction turned out to be beneficial. With profits like this, the Puerto Rican resident could stabilize their finances, pay off debts, buy another house and if he wants, even buy a boat and a summer house in Culebra. His retirement is guaranteed.

Meanwhile, with this overpriced purchase, the foreign investor was spared from paying taxes in the United States thanks to the benefits of having a decree. However, the situation creates a problem for the appraiser and the Puerto Rican market, because it increases the prices of an entire sector based on that sale.

With these real examples of two people he knows, realtor Zavala Steidel illustrated the dynamics that are becoming more frequent in Puerto Rico’s real estate market.

For the realtor, this is the best example of “a voluntary displacement” in which a native Puerto Rican is “willing to sell to you for $13 million” the house of their “dreams” in exchange for the enormous financial opportunity that comes up.

He said that, based on his experience, some of the factors that have sparked real estate market prices to skyrocket are Act 22/Act 60 benefits and the social change prompted by the pandemic with the proliferation of remote work. It is evident that this trend has translated into the arrival of more foreigners to work from the Isla del Encanto.

After the law was approved in December 2012, it took a while for it to be marketed and for investors to set their sights on Puerto Rico, mainly motivated by the security that a territory of the United States can give them, the savings in tax payments and capital gains, and savings represented by the purchase of properties in Puerto Rico compared to the value of similar properties in other United States jurisdictions.

The median value of properties in the United States has also registered an increase since the pandemic, but in Puerto Rico that value spike is significantly higher. In June 2022, the increase in the United States was 91% when compared to the average from 2015 to 2019, while in Puerto Rico it was 124%, former Builders Association President Emilio Colón estimated.

“Other places in the Caribbean have these incentives, but we have them with a big difference: we are a United States territory and for them it represents stability. I’m still an American and I’m home, in the United States,” said Zavala Steidel, referring to the allure of the tax decrees.

For the real estate broker with more than 30 years of experience in the market, the large number of sales in cash and above the appraisal value of the property means that Puerto Ricans have greater challenges to access a home.

University professor under anonymity

“It’s like there’s a network of rules and players that you just can’t compete with.”

“There’s an external force that has made prices no longer affordable for Puerto Ricans. The main driver of this is Act 60 [formerly Act 22]. This would never have happened only with Puerto Ricans, never, never, because our economy is different,” he said after pointing out that whoever wants to sell and wants to do it for the highest profit margin, first thinks of a foreigner, because an image has been created that they are the ones who have the money to buy.

He pointed out that since the market does not respond to our economy or to the pockets of the locals, this has caused an accelerated increase in property values, which if continues, could lead us to an experience like that of Hawaii where locals can no longer buy.

“Remember that this is like when you’re bitten by a mosquito. You have the symptoms later, but you are already infected. So, we’re already infected. What happens is that now we’re seeing the symptoms of what’s happening. It is not a matter of will it happen, it has already happened,” Zavala Steidel said, referring to the fact that Act 22 was approved in 2012, but its effects, accelerated by disasters such as Hurricane María and the pandemic, have not been evident until now.

Scarce social interest housing and a hold-up in Plan 8

The problems brought on by exaggerated prices not only in the purchase and sale of properties but also in rentals are coupled with the need for social interest housing that for years no one has supplied, said Raúl Santiago Bartolomei, a professor at the Graduate School of Planning of the University of Puerto Rico’s Río Piedras Campus.

“There’s a demand for this affordable social interest housing that nobody was supplying. That has been dragging on for a long time,” he explained.

One of the problems with the Section 8 Program is the lack of inventory, the non-compliance with requirements imposed by HUD and the discrimination by owners who refuse to validate the vouchers of participating families because in the current market these owners can generate more income renting or selling to speculators, said Attorney and Co-founder of Ayuda Legal, Ariadna Godreau.

Godreau added that another phenomenon that occurs with this program is that houses that wish to participate must meet the fair market value and the rent cap established by HUD for a home to be part of Section 8.

“In a speculative market, where Act 60 exists, in a market in which people pay cash for their purchase, where there are no appraisals… If I, as the owner, can rent a house for $1,000 [a month], why am I going to rent it to someone through Section 8 in which the maximum is $750?” Godreau said.

She said the discrimination is evident since when the property is advertised as available; some owners establish they not accept vouchers or refuse to talk to the client starting with the first call because he or she speaks Spanish.

Santiago Bartolomei said the jump in real estate prices and sales has been evident since 2016, the year when there was a spike in the list of short-term rental properties. In 2017 there were 4,243 short-term rental units in Puerto Rico; that number had risen to 17,138 as of June 2022, according to the most recent study that Abexus Analytics published in November.

Between 2018 and 2021, the single-family home price rate in Puerto Rico increased by 22%, according to the Federal Housing Financing Agency’s House Price Index.

Government must step-up

The government of Puerto Rico promotes attracting these supposed investors under the premise that the decrees have no direct cost to its coffers, without evaluating their impact on the housing market. Some, for example, in addition to buying and renting properties as a residence, have registered corporations to buy properties and turn them into short-term rentals in some places in San Juan — such as Miramar, Santurce, Río Piedras — Isla Verde, in Carolina, Rincón, and the offshore towns of Vieques and Culebra, Santiago Bartolomei has confirmed.

The expert argued that if the government does not assume an active role in ensuring affordable social housing, it becomes an accomplice to the problem. Rather than acting as a facilitator by granting and promoting incentives, the government must discourage real estate speculation and promote affordable social housing, whether through new construction or rehabilitating abandoned properties, he noted.

Meanwhile, Zavala Steidel proposed that the government should promote urban revitalization and give priority to local owners when selling government properties, as well as encourage banks to conduct bulk sales of repossessed houses when they have a high inventory, so that they can be used to meet the need for affordable housing.

“The government of Puerto Rico and its dependencies should not sell a property without first offering it to a local person within the first 60 days. To Puerto Ricans first, especially properties that have cultural, architectural, and ecological value,” the real estate professional said.

A perverse incentive?

Giancarlo González Ascar, co-founder and Chief Information Officer of Urbital, a platform that monitors real estate prices in Puerto Rico and sells properties, believes the increase is not just a Puerto Rico problem. He argued that because of the pandemic, prices skyrocketed everywhere, and Puerto Rico is no exception, so he believes that, contrary to public perception, attributing this spike only to Act 22 and the proliferation of short-term rentals is to ignore other factors that have also had an effect.

He explained that many Puerto Ricans who bought just before the real estate crisis of 2008 have been paying mortgages well above the real value of their property. He added that the current boom in Puerto Rico’s real estate market “is positive” because it is a change from what was experienced after the real estate bubble burst: property prices plummeted and many had had to surrender them to banks or sell them assuming the loss because they could not pay their mortgages or sell them at the original price of the loan they had signed.

“Even now, when people are talking about gentrification, about the bubble, that there are no affordable houses available, there are still people selling for less than what they bought for. These are Puerto Ricans selling at a loss and giving up their houses. These were Puerto Ricans who bought their house and for 10 years they paid for something that was worth less,” said the government’s former Chief Information Officer. “And suddenly, we’re seeing pockets of recovery and appreciation, and people are saying: ‘No, this is bad, this should be eliminated?’ Wait a minute, let’s look at all the factors.”

Despite González Ascar’s observations, the truth is that for Puerto Ricans, access to affordable housing is increasingly uphill. For example, data from the Affordable Housing Index, prepared by Estudios Técnicos Inc., shows a consistent drop in the possibility of accessing a mortgage loan that allows people to buy a home. This index is measured from percentages and the closer the value is to 100%, the more likely it is that a family can buy a home.

However, Economist Leslie Adames, the entity’s director of Economic Analysis and Policy, said the most recent figure for the index shows that a typical family has only 54% of the income needed to qualify for a mortgage loan, which represents a drop compared to 62% in December 2010. He said this responds to the “ongoing jump in the housing unit sale prices and in mortgage interest rates.”

The Puerto Rico Housing Secretary believes that the interest rate increases that President Joe Biden’s administration has approved will be positive for the local housing market.

“When you trigger an interest increase, it automatically makes the possibility of taking out loans more expensive, of being able to buy goods and services to a certain point and what that does is that it levels out the field. Those who were going to invest just to invest, or buy just to buy something that was not a necessity, will now hold off and maybe move on to other investments, leaving the opportunity open for people who need to buy a home,” Rodríguez argued.

Economist José Caraballo Cueto disagrees. He said that far from promoting a greater availability of affordable housing inventory for Puerto Ricans, the interest rate hikes make the situation harder for local families. He explained that foreign investors are not affected by this increase in rates because they usually do not finance their purchases through the banking system, contrary to workers, who now find it more expensive to take on a mortgage.

“It will make it harder for working families to buy a home,” he said.

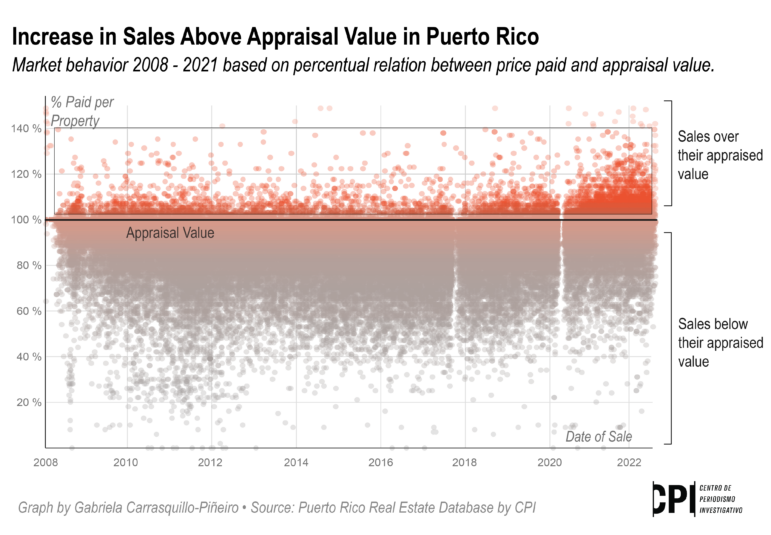

Following the real estate crisis that began in 2008 in Puerto Rico, property prices plummeted and sales under appraisal jumped. This trend began to change as of 2018, and even more so since 2020, with a significant increase in sales over appraisal value and a reduction in sales under appraisal value. These continue to happen, but to a lesser degree, as evidenced by the analysis of the CPI’s database.

The real estate market responds to economic cycles, said Economist Antonio Fernós Sagebien. He explained that the sale of properties in cash is beneficial for the sellers since they can do it faster, without the need for intermediaries and with a high possibility of making a profit on a property for which they were paying the bank above its value.

“There’s a long list of people who bought when prices were very high. They dropped and right now the balance owed on the mortgage is greater than the property’s market value, which serves as a guarantee for what is known as that they’re under water,” said Fernós Sagebien.

The problem comes up when this type of sale happens in abandoned buildings in areas where low-income people reside, and the new owner makes an investment that increases the value of the property and its rental fee.

“The new owner makes an investment and decides to increase the rental fee. It’s a very delicate issue that must be looked at very carefully because it isn’t as easy as saying that the owner, the new owner, is the one who decides and that’s it. You have to be very careful with the things that happen and the economic incentive structure, so that it won’t become what is called in economics ‘a perverse incentive’,” he said.

A perverse incentive is when a strategy designed to promote an economic activity, ends up being detrimental. Fernós Sagebien argued that a “solidarity economy” that is sustainable must be developed.

As for guaranteeing better housing conditions, “the State should play a more active role, but its insolvency due to the bankruptcy [of the Government of Puerto Rico] may not allow it to have the resources,” the economist said.

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.