Just as a vulture is a bird of prey that feeds on dead flesh, a vulture fund is an investment firm with a similar taste: its main food source comes from countries in crisis, especially from public corporation debt. And those firms have already landed in Puerto Rico, after their journey through countries in economic ruin such as Argentina, Greece, and Spain.

Just as a vulture is a bird of prey that feeds on dead flesh, a vulture fund is an investment firm with a similar taste: its main food source comes from countries in crisis, especially from public corporation debt. And those firms have already landed in Puerto Rico, after their journey through countries in economic ruin such as Argentina, Greece, and Spain.

In Puerto Rico, vulture funds hunger after, for example, the debt of the Puerto Rico Aqueduct and Sewer Authority (PRASA), for the high cost of water ensures profit. Already three vulture funds have acquired almost all of PRASA’s debt.

They also have a taste for General Obligation bonds, with which the government asks for loans under the good faith, credit, and taxes of the Commonwealth. Besides, the GO bonds carry a constitutional repayment guarantee.

These funds are also hungry for Sales Tax Financing Authority (known as COFINA) bonds, and the bonds of the Retirement System, the Government Development Bank and of the Highways and Transportation Authority, even though these last two don’t have enough bond availability in the market to satisfy them.

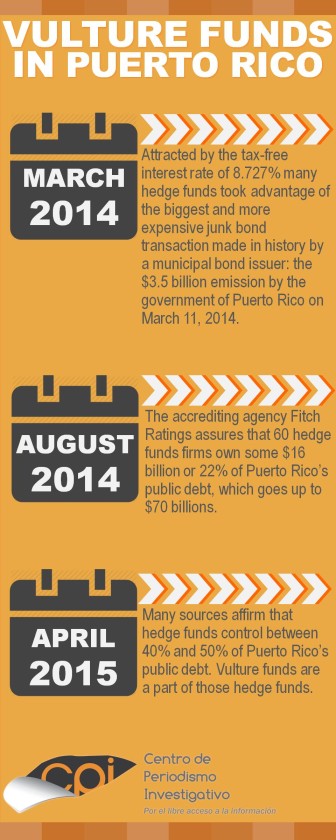

What these funds like and dislike was highlighted by financial industry sources to the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI). These sources stated that currently between 40 or 50 percent of the debt of the government of Puerto Rico is under the control of hedge funds, which in turn are part vulture funds.

“All of a sudden the value of all of the bonds of Puerto Rico dropped. And that’s when the vulture funds arrived.” Those are the words used by a financial advisor to describe the recent interest these funds have in Puerto Rico bonds.

Where do vulture funds come from?

Vulture funds are investment companies, mainly from the U.S., that belong to a group of firms known as hedge funds. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the federal agency that is supposed to regulate the securities market, does not distinguish between hedge funds and so-called vulture finds.

The SEC describes hedge funds in general as a kind of fund that uses speculative investment strategies with less federal regulations, and which only individuals with high incomes, known as accredited investors, may buy.

Still, experts from the financial sector and lawyers familiar with Wall Street do include and distinguish vulture funds among hedge funds, CPI confirmed.

“Vulture funds as such are funds that search for bonds and stocks of companies and countries that they perceive to be under economic pressure and that have a high non-payment risk. But not all hedge funds do that; it’s only a sub-group within the universe of hedge funds that dedicate themselves to this type of investment,” specified Sergio Marxuach, public policy director at the Center for a New Economy.

“We call them vulture funds because traditionally they have not been interested at all in investing in bonds of Puerto Rico. If you go back five years, none of these funds were there. They look for crisis and many times when they take advantage and invest in such a situation, they worsen the crisis of the entity in which they are investing. It’s a manner of investing that adds nothing to the economy in the long term, and charges high fees for the use of their services,” added Stephen Albrecht, financial advisor of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) is a fine example of how vulture funds deepen a crisis: bondholders, in case of a new transaction, could ask for “fixed assets,” as guarantee, that is the public corporation’s buildings, plants, equipment and land.

Speculative Strategies

Hedge funds and vulture funds use a number of investment strategies to take advantage of economic crises. One of these, according to the SEC, is the concept of short selling, a strategy through which investors sell at a high price today, and in a short period of time – say, from six to nine months – buy once again at lower prices, pocketing the difference as profits.

In Puerto Rico this is also reflected in PREPA, where vulture funds “want a restructuring and to get their money out as fast as possible. What they are interested in is a quick profit, in other words, they care very little what happens in Puerto Rico’s economy in the long run. These funds are there to provide liquidity to the government of Puerto Rico, but it will be at a much higher price than before,” Marxuach said.

“Puerto Rico has increased its dependence in nontraditional investors that tend to have short range investment strategy, which adds to our level of concern,” said New York’s UBS firm in its Puerto Rico Credit and Market Update report.

Vulture funds’ speculative strategies have been denounced at an international level. Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky, independent expert of the United Nations Organization on the consequences of external debt, said that vulture funds “are an obstacle to the settling of debts of states and are a threat to human rights.” For this reason, last month Bohoslavsky demanded from the UN a greater regulation of private commercial entities of the financial sector such as vulture funds.

“Not only are the least developed countries a target for these vulture funds but increasingly highly developed countries have become targets as well,” warned Bohoslavsky.

How did they land on the island?

How did they land on the island?

Lured by the fat, tax-free 8.727% yield (the real interest rate paid), hedge funds would not let pass what Bank of America Merrill Lynch described as the largest and costliest junk bond transaction in history carried out by a municipal bond issuer: the $3.5 billion emission by the government of Puerto Rico on March 11, 2014.

Without warning about the consequences of such a transaction, top administration finance officials, including commonwealth Chief Public Financial Officer Melba Acosta and Government Development Bank Chairman David Chafey, were photographed with their GDB lieutenants giving celebratory smiles and high fives on the outside deck of Morgan Stanley’s Wall Street headquarters beneath a sign that read “Congratulations Puerto Rico $3.5 Billion Landmark Municipal Transaction”.

But since end of last year, the now GDB President Melba Acosta has been discussing efforts to broaden Puerto Rico’s investor base, as arranging bond deals has become increasingly difficult because of the increased demands of hedge funds and the increasing unwillingness of lawmakers to comply with them.

Since Puerto Rico’s traditional municipal market investors, who are conservative by nature, have been scared off by the its downgrade to junk bond status, the commonwealth has had to rely on hedge fund investors, who are usually invest for the long haul.

“We want to see how to access other investment groups. You have the municipal market investors, hedge funds and their investor groups that purchase sovereign debt. These people have metrics that we don’t necessarily or typically use. So we are putting thought into how we can access them,” said Acosta.

Access to these new investors will require that Puerto Rico balances its budget, improves its financial reporting and becomes more transparent, according to investment analyst Charles Blitzer.

As part of this requirement, the GDB hired the services of a consulting firm that has in its ranks former officials from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in order to incorporate more rigorous financial information requisites. The entity also hired Todd Hagerman as investor relation’s specialist. Hagerman has worked for the main banks in the U.S. and for the Federal Reserve Bank. He recently organized Rockwood Capital, a real estate investment firm that manages $6 billion in funds and has offices San Francisco, Los Angeles and Nueva York.

The idea is to have more timely reporting across all government entities that would give a clearer picture of Puerto Rico’s debt and cash positions. It will put Puerto Rico into a position to be able to meet IMF financial reporting standards demanded by all sovereign debt investors.

For some hedge funds, the March deal presented a golden opportunity to invest in Puerto Rico, where a decade long economic downturn had whacked down the value of assets like real estate and local stocks and now government bonds, presenting opportunities for big profits from the deep-pocketed hedge funds that take big risks in pursuit of large gains.

Firms such as Paulson & Company, Och-Ziff Capital Management LLC, Fir Tree Partners, Perry Capital LLC and Brigade Capital Management each purchased more than $100 million of the issue.

An example of the pressure and the level of influence that vulture funds put on Argentina is clear in the fact that while these represent just 1% of bondholders, they did not agree with the debt restructuring achieved by that country in 2004 and 2005 with 93% of bondholders. Since then vulture funds have been litigating on New York’s South District Court, before judge Thomas Griesa, who determined that Argentina has to pay 100% of its debt with the vulture funds that did not accept the restructuring. The government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner continues appealing the decision in New York, while investing millions in the process.

The firms that purchased Puerto Rico’s bond issue also include Third Point, Appaloosa Management, Farallon Capital Management, Avenue Capital Group, Maglan Capital, Matlin Patterson, Highbridge, PSAM, Apolo, Angelo Gordon, Fundamental Advisors, Arrowgrass, Marathon Asset Management, Pine River Capital Management, Knighthead Capital Management, Davison Kempner, Candlewood Invest Group, Meehan Combs and Blue Mountain Capital Management.

The government’s not clear on who has the island’s bonds

The bonds are first purchased in a primary market. That is when an investor or a firm buys the original bond emission directly from the government. But if in turn these investors decide to resell the bonds to third parties, they carry out the transaction in what is known as a secondary market.

“There the investors sell the bonds to another person or entity in a transaction that has nothing to do with the government of Puerto Rico. What they have is bonds that say that the government of Puerto Rico will pay ‘such and such’ interest and principal by a certain date. And if they need to sell them before that date they search for another person who is interested in buying them. Usually this sales transaction is carried out through a broker such as UBS or Popular Securities. They have the task of finding a buyer, and the investor sells those bonds to that buyer at a price they mutually agree on; that’s the secondary market,” explained Marxuach.

“Hedge funds can be bought in both markets, but vulture funds specifically usually buy first in the secondary market at very low prices, because that is where they see the opportunity of reselling them at a higher price after restructuring,” the economist added.

Although there isn’t any detailed information on who has what amount of the island’s debt, bondholders’ influence in the public policy decision of the island’s is increasingly evident.

Between May and April 2015 the government of Puerto Rico plans to make a new bond issue. Among the aspects that complicate the transaction, according to Acosta, are the bondholder’s doubts on tax reform, PREPA and the decline in tax revenues.

El problema no es los buítres. El problema es la caroña. Los buítres no matan lo que se comen. Se comen lo que ya está muerto.