The 10 empty liquor bottles are the color of seaweed and mud. Once they were litter on the streets of the East Garfield Park neighborhood in Chicago. But now, clean and sparkling, the bottles are on display some 2,000 miles away at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, part of a work by artist Edra Soto.

Seashells made from plaster surround the bases of the bottles, referencing the sandy ocean shores of Puerto Rico, where she grew up. As if forming an altar, this eclectic combination of objects marks the artist’s passage from the island to the Windy City, and her continuing connection to both places.

Soto’s work is part of the exhibit “Repatriación,” featuring Puerto Rican artists currently based in Chicago. Soto came to Chicago for graduate school at the School of the Art Institute 20 years ago, and has never returned to live in Puerto Rico, where her mother still resides.

“My family is here, and my life is here,” she says of Chicago. “So I just cannot leave. But that is very hard for me.” One of Soto’s recent works in Chicago explores this split in her identity through images of rejas, the patterned iron grillwork, and quiebrasoles, the decorative concrete walls, that protect windows and porches across the island.

Photo by Camille Erickson

Puerto Rican artist Edra Soto

The MAPR exhibition is co-sponsored by Chicago’s National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture, one of many Puerto Rican organizations in Chicago that host cultural events, provides social services and works on political issues related to the island and the Puerto Rican diaspora. These missions have only become more crucial, since the island’s ongoing debt crisis and hurricanes Irma and Maria have driven an increasing exodus to the mainland.

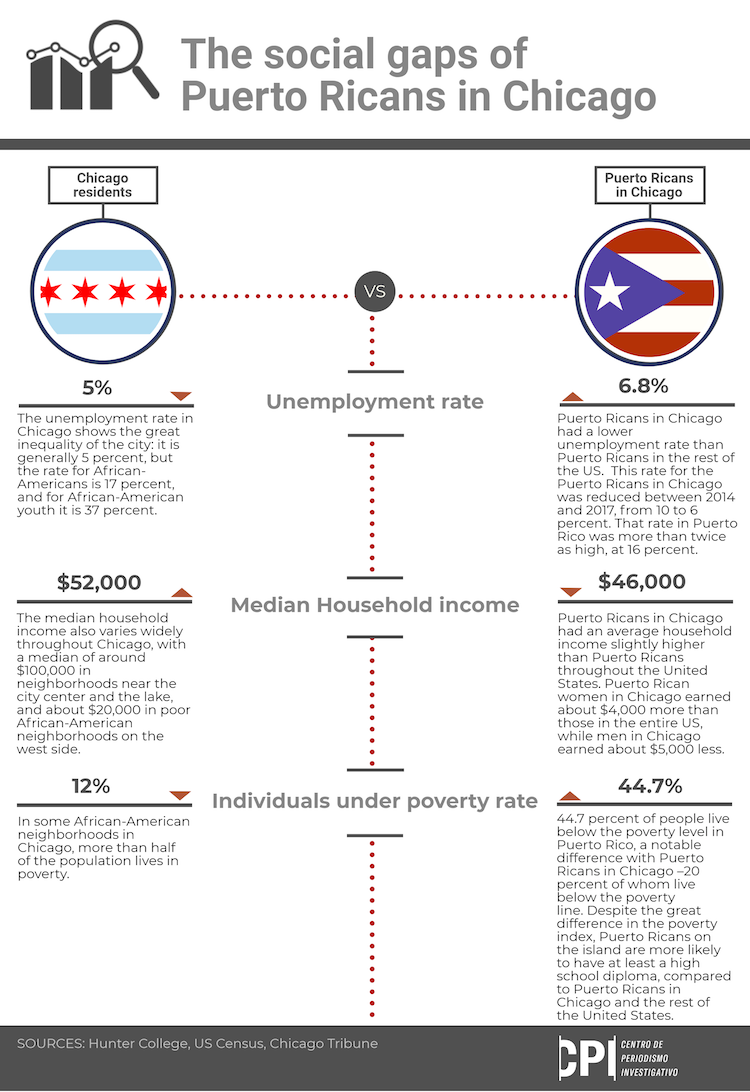

Puerto Ricans in Chicago and other U.S. cities have higher incomes and employment rates and lower poverty rates than those on the island, according to data from the US Census and Hunter College analyzed by the Center for Investigative Journalism and Northwestern University.

Puerto Ricans in Chicago also have higher employment rates and incomes, and lower poverty rates than Puerto Ricans on the US mainland as a whole.

But living in a city like Chicago – with a dearth of affordable housing, troubled public schools, infamous segregation and frigid winters – presents new challenges for those coming from the island. Puerto Ricans in Chicago are less likely to be employed than Chicagoans as a whole, and median household income for Puerto Ricans in Chicago was lower than for Chicagoans on average.

Puerto Ricans in Chicago fared similarly to those in the Orlando metropolitan area and in New York City on most indicators, though the poverty rate in New York is much higher and home ownership rates are lower – likely because that city’s housing is even more unaffordable than Chicago’s.

The struggles faced by Puerto Ricans arriving in Chicago in recent years meanwhile are nothing new for a diaspora community that has long faced obstacles and disparities in the Windy City going back at least a half century. And long-time Puerto Rican residents and community institutions in Chicago are still helping hurricane evacuees and other more recent arrivals to rebuild their lives and contribute – whether in the short- or long-term – to the city’s future.

A history of resistance

Chicago is home to one of the nation’s largest and most organized Puerto Rican communities in the United States. With about 97,000 Puerto Rican residents, the Chicago community is smaller than in cities like New York, Philadelphia and Orlando. In the wave of migration stateside that followed Hurricane Maria, Illinois was the tenth most popular destination, according to a 2018 study.

Chicago has a significant political and cultural presence and a deep history that can be traced back to the social and economic transformation of Puerto Rico in the mid-20th century.

In the 1950s, an estimated 450,000 Puerto Ricans left the island thanks to skyrocketing unemployment, the industrialization efforts of Operation Bootstrap and state-sponsored work programs on the US mainland that incentivized moving to the states. Many of them came to Chicago, then a hub for factory, industrial and service jobs. By the 1960s, Chicago was home to more than 32,000 Puerto Ricans.

Here, Puerto Ricans found a racially segregated city plagued with many of the same social problems they were fleeing. Similarly to other ethnic minorities in the city, Puerto Ricans experienced poor housing, police brutality, inadequate education, ineffective healthcare, inhumane work conditions, and other social issues. Chicago’s systematic racism coupled with the larger US Civil Rights Movement throughout the 1960s led Puerto Ricans to organize in ways they couldn’t on the island. As US citizens, Puerto Ricans who moved to Chicago could vote in US elections, and thus assert more powerful political agency than they could in Puerto Rico.

A pivotal moment in the community’s history came on June 12, 1966 when, after Chicago’s inaugural Puerto Rican People’s Parade, a Chicago police officer shot a 20-year-old Puerto Rican man, Aracelis Cruz, in the leg. The shooting sparked community outrage and led to a three-day uprising in Chicago’s West Town neighborhood. This in turn led to the creation of significant community organizations like the Puerto Rican Cultural Center and Chicago’s Young Lords Organization, a Puerto Rican street gang turned grassroots civil rights group modeled after the Black Panthers.

Ralph Cintrón is an Associate Professor of Latino and Latin American Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago where he’s studied Chicago’s Puerto Rican community. Cintrón says since the late 1960s, Chicago’s Puerto Rican community has been “tremendously organized.”

“The organizational force comes from Puerto Rican political leadership in the city that is very much oriented towards a kind of cultural revival, cultural maintenance, political independence for the island, and so on,” he says.

Cintrón describes the organization of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community as “remarkable.” He says the leadership of the Puerto Rican Cultural Center coupled with various social service institutions and affordable housing agencies has created a “concentration of effort and devotion to the community itself [that] is completely unusual, completely remarkable, [and] not anything that you see in New York City, Miami, Orlando” or anywhere else around the country.

Cintrón says a significant reason why Puerto Ricans in Chicago were able to organize themselves in ways that aren’t seen in other cities is because of the community’s more homogenous politics.

“Puerto Ricans in New York City, historically, have been very varied in terms of their political orientations,” he says. “But Chicago has been very specifically oriented ideologically to the independence movement and to certain kinds of social justice programs both locally as well as on the island.” Puerto Ricans in Chicago have had their own experiences of marginalization and gentrification and have, over many years, been quite articulate in their analyses of United States colonialism over Puerto Rico, says Cintrón, up to and including the effects of the recent financial crisis and Hurricane Maria.

“If one adds to all this the fact that the Puerto Rican community is smaller in Chicago and not as widely dispersed, as on the East Coast, then the concentration of political activism over a long period of time makes sense,” he says.

After being forced out of several other neighborhoods through urban renewal and development, Puerto Ricans organized mostly in the Humboldt Park neighborhood on the West Side in the latter part of the 20th century, determined to maintain a community of their own. Though Puerto Ricans live throughout the city and the surrounding suburbs, Humboldt Park remains the cultural and symbolic center of Puerto Ricans in the Midwest. Puerto Rican businesses, arts, community centers, nonprofits, schools, music, and flags are all prevalent throughout the vibrant neighborhood, especially on the Division Street strip known as Paseo Boricua.

Photo by Michelle Kaanar

Humboldt Park’s Paseo Boricua

In recent years, the community has been instrumental in keeping Puerto Rican concerns on the radar of the city at large. Chicago Puerto Rican leaders were instrumental in securing the release of the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN) political prisoners, most of whom were based in the area – the 12 pardoned by President Clinton in 1999, and Oscar López pardoned by President Obama in 2017. Cintrón points to the organizing around López’s case in particular as emblematic of the kind of power Chicago activists has been able to leverage in service of a cause.

Chicago was also a bastion of support for the movement to end military bombing in Vieques. And a big part of the Puerto Rican community also has built strong ties to and become part of the Democratic Party establishment in Chicago, including former Congressman Luis Gutiérrez, former city councilman Billy Ocasio – who organized the Repatriación exhibit – and numerous other local elected officials.

Chicago’s Puerto Rican community has also been a robust resource for boricuas impacted by the debt crisis and, most recently, Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

An exodus and an influx

On September 25, 2017, a United cargo plane full of emergency supplies landed in San Juan, coming from Chicago. It was the first private relief flight to make it to the island after Hurricane Maria; it returned to Chicago the same day carrying 300 passengers who had been stranded on the island. In the next months, additional planeloads of supplies have been sent from Chicago to Puerto Rico.

The flights were among multiple ways Chicago Puerto Ricans contributed in the wake of hurricanes Irma and Maria, both with immediate aid and longer-term rebuilding. Among other things, the advocacy group Puerto Rican Agenda has made micro-grants of a few thousand dollars each to 40 different municipalities. The Puerto Rican Cultural Center has made grants to institutions including an art and design college in San Juan. Segundo Ruiz Belvis Cultural Center and the Puerto Rican Arts Alliance have also helped Puerto Rican artists perform in the US, after venues on the island were destroyed and opportunities disappeared.

Immediately after the 2017 hurricanes, Chicago Puerto Ricans also saw a need to coordinate aid to Puerto Rican evacuees arriving in Chicago, many with children and some with little but a suitcase full of summer clothes.

On November 2, 2017, the city opened a temporary resource center in the Humboldt Park field house in the park that gives the neighborhood its name. The center helped people file for individual assistance from FEMA and access a range of services, from flu shots to temporary housing. The one-stop shop stayed open through early May of 2018, and aid to evacuees has continued beyond its closing. Finding affordable housing has been a particular ongoing struggle, and many evacuees have found that promises from the city public housing authority have not panned out.

Chicago’s 26th Ward alderman Roberto Maldonado, whose ward includes Humboldt Park, says that as recently as December 2018, post-Maria migrants were still coming to his office for help.

“Some people keep coming back just to socialize,” he says, “but others [come by] because they need better housing accomodations. That is the biggest issue. People want to live close to family and to the community – they want to hear Spanish being spoken and salsa music – but most of the [Chicago Housing Authority] housing that is being made available to them is on the far south side or the far north side. They come to us wanting us to intervene, but there’s very limited housing in Humboldt Park – there just aren’t any vacancies.”

From October through December of 2018, the Puerto Rican Cultural Center conducted outreach on behalf of the city to 978 people still in Chicago who came through the field house in the months following Hurricane Maria. The organization contacted 403 of them to inquire about housing, employment, health care, and more. Natasha Brown, of the PRCC says that they learned that many people still need help with basic benefits such as Medicaid and food stamps, and she reiterates Alderman Maldonado’s point.

“We see a lot of housing instability. People are still in shelters, more than a year later. They may have signed a lease but they still haven’t been able to move into an apartment.”

The PRCC is continuing to work with evacuees on an as-needed basis. Such ongoing efforts may help determine the future of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community – a diaspora with deep roots in and a constant ebb and flow between both the Midwest and the island 2,000 miles away.

A different world

As a child José Vélez enjoyed visiting Disney World in Florida, but he never saw himself living on the US mainland.

After the hurricane, the hotel that Velez’s mother worked at in Puerto Rico transferred her to a hotel in Colorado. Vélez, then 18, moved with her that fall. They had no family there, and few people spoke Spanish – it was lonely, he says.

Photo by Kari Lydersen

Jose Velez

Then through a friend they connected with the Puerto Rican Cultural Center and decided to move to Chicago, where the organization helped them find an apartment and work. Vélez’s two cousins also moved to Chicago to join them in February 2018. Now Vélez works for the cultural center, and thanks director José López for helping him understand how colonialism affects the island – including his hometown of Guayama, where residents deal with toxic emissions and ash from the nearby coal plant.

Vélez wants to go to college on the US mainland, studying sociology or law, and return to Puerto Rico so he can help people on the island.

His brothers, father and grandfather remain in Puerto Rico; the separation was especially hard during the holidays, when Vélez missed the nonstop celebrations he’s used to in Puerto Rico – the lechón, the Three Kings Day gift exchanges. And the “súper diferente” culture in Chicago has been a big adjustment. In Chicago people pass on the street without saying hello, Vélez notes; in Puerto Rico even strangers greet each other and say “buen provecho” when someone is eating.

Vélez never stops missing Puerto Rico, and he hopes he can indeed return to work there one day. “When I was young I never imagined I’d leave my country,” says Vélez, in Spanish. “I think about it every day.”

Seeking aid, providing help

Born in Cleveland to activist parents, Rebecca Sumner Burgos has spent time in New York, Paris, and Berlin, and lived in Chicago for a bit as a child. She’s been a performer and a translator and has done community work within the LGBTQ community. When Hurricane Maria hit, she was living in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, and serving as development director and alumni coordinator for a Methodist school.

Her job was eliminated in the wake of the hurricane; she tried to apply for unemployment benefits in Puerto Rico, going in person to the office for weeks on end, to no avail. Then after her mother died in May 2018, Sumner Burgos thought it was time for a change. “It seemed like Chicago was a secret, a place where you could reinvent yourself,” she says.

Photo by Martha Bayne

Rebecca Sumner

She moved in with a friend in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, and soon found some work. She also went to city councilman Roberto Maldonado’s office and then the field house resource center to get help with health insurance. Sumner Burgos shies away from identifying as an “evacuee,” and notes she had more resources and experience to draw on than many people affected by the hurricanes. She knows the financial and other stress she experienced around the storms and upon moving to Chicago were amplified for many others.

“I am a single woman, I don’t have children, I’m not the head of my household, so I can only imagine how desperate other people were when they got here,” she says. “My class position and education afforded me a level of privilege that is really important to recognize.”

She now has a job helping Puerto Ricans including evacuees – and Chicagoans of other backgrounds. She is the outreach coordinator for La Casa Norte, a Humboldt Park nonprofit serving people experiencing homelessness.

The work helps her deal with her own trauma – flashbacks to the hurricane and bouts of uncontrollable crying; and with the guilt she feels about leaving Puerto Rico. “I come from a very Puerto Rican nationalist family, so leaving felt like a failure, and an abandonment of my people and my country,” she says. But she plans to stay in Chicago for the foreseeable future.

“My life is unrecognizable to me,” she says, “but I’m just going to keep going with whatever script this is.”

Tastes of home

Roberto Pérez couldn’t find Caribbean cooking classes or food in Chicago, so he decided to teach himself how to cook and start his own culinary business.

Pérez, 44, is Puerto Rican, though he was born in Chicago in the West Town neighborhood. In 2012 he and his friend Angel Fuentes co-founded Urban Pilón, a culinary company dedicated to sharing foods and cooking techniques from Puerto Rico, the Caribbean and Latin America. On Dec. 5 he marked his 100th event with Urban Pilón: “Santísimo Sancocho,” a celebration of the traditional Latin American stew, at the Segundo Ruiz Belvis Cultural Center in Chicago.

Photo by Katie Rice

Roberto Pérez

Among the sounds of bomba music, attendees enjoyed four types of sancocho: “sancocho Santa Anacaona,” a beef stew; “sancocho Santa Inocencia,” a vegetarian stew; “sancocho santo,” a seafood stew; and “sancocho siete potencias,” which included seven different meats.

Chicago’s Puerto Rican community is very nostalgic, Pérez says, and people want to hold on to their culture.

“Puerto Ricans in Chicago have really put a stamp on who they are and where they are, and I think people in the diaspora in general really are like, ‘Wow, I wish I could have something like that in my city,’” Pérez says. “Even though Orlando may have a bigger community, people would say that the Puerto Ricans in Chicago are more organized and politically stronger.”

Whenever Pérez is in need of inspiration for his cooking — or when he needs to get out of the bitter Chicago winter — he visits his mother in Ponce, Puerto Rico, and travels the other Caribbean islands looking for new flavors and new cooking methods.

“Puerto Rico really inspires me,” he says, “every time I go.”

Family separation and migration

Vanessa Gómez, 44, and her daughter Verónica Díaz, 14, survived Hurricane Maria in their home in Caguas. Traumatized by the storm and its aftermath – no electricity, rationed gas, an influx of National Guard that made their neighborhood “look like a war zone,” as Díaz put it – she left in late September 2017 on a “rescue cruise” to join her father in Florida.

Gómez stayed on the island, living with her 68-year-old mother, who has kidney problems. But her mother and her aunt, who was 76 and has Alzheimer’s, struggled to get adequate health care after the hurricane. So the women decided to move to the mainland. When Gómez’s mother went to a housing office in Puerto Rico, she was advised not to move to Florida because it was “overcrowded.” The three decided to move to Berwyn, a suburb of Chicago, where Gómez’s brother lived. Gómez’s mother and aunt were the first to leave; they arrived in the Chicago area on Feb. 1, 2018. Gómez stayed on the island a little longer to settle the family’s affairs and arrived in Chicago on Feb. 28.

Vanessa Gómez y Verónica Díaz

The three women settled into life in Berwyn, an inner-ring western suburb, where Gómez took care of her mother and aunt full-time, still separated from her daughter while waiting for Díaz to finish the school year in Florida. Díaz moved to Berwyn and joined her mother last June after finishing seventh grade.

Gómez and Díaz have a close relationship, and they joke and laugh when talking about their experiences in the Chicago area. Díaz talks about drama in her middle school while scrolling on her phone, shopping for a dress for an upcoming school dance. Gómez teases her.

The transition to life on the mainland has had its difficulties, and the move has had mixed results for the family. Gómez’s mother and aunt receive better medical care here, and Díaz’s school has better resources than her school in Puerto Rico, Gómez says. But the transition has been hard for everyone. Díaz had to drastically improve her English to keep up in school while taking courses less advanced than those she was taking in Puerto Rico.

“Right now, I’m telling Verónica to take advantage of the opportunity and the sacrifices we’re making,” Gómez says. “There are two important things for me: that we should enjoy the time that we’re here, and that we learn and [Díaz] manages to prepare herself academically.”

Family separation has been a difficult result of the hurricane and subsequent migration for the family, like many Puerto Rican evacuees on the mainland. Gómez and Díaz were considering a move to Florida to be nearer to Díaz’s father, but have since decided to stay in Chicago since it offers better opportunities for Díaz, said Gómez. Both women continue to miss Puerto Rico.

“One’s land always calls,” Gómez said.

Leaving and returning

Maricarmen Hernández Galarza, a public health worker from Caguas, moved to Chicago in October 2017, just a few weeks after Maria, with her parents and her 10-year-old son, Caleb, who has autism.

The family sought help first at the office of Congressman Luis Gutiérrez, and then at Ruiz Belvis Cultural Center; the field house welcome center in Humboldt Park was not yet open. Eventually the family found temporary housing in Humboldt Park through the social service organization Casa Central.

They were promised a public housing apartment in December (by the Chicago Housing Authority, or CHA), but the holidays came and went without it materializing.

Photo by Michelle Kanaar

Maricarmen Hernández Galarza

Her parents, frustrated by the struggle to find housing, returned to San Juan later that winter. Hernández and her son eventually moved into a CHA unit in the diverse North Side neighborhood of Rogers Park in the spring. Still, life was stressful.

In Puerto Rico, Hernández says, Caleb was in a good public school with access to the help he needed, including speech therapy and psychological counseling. But in the Chicago Public Schools system, she felt he was being neglected. She pulled him out of school in late February and home-schooled him instead; but that made getting a job essentially impossible.

Meanwhile, she says, Caleb was unhappy and depressed. She sought help through one of the city’s mental health clinics, but was told it would take a year for Caleb to get an appointment, she says. Hernández had originally wanted to make a new life in Chicago, but she and Caleb wound up moving back to San Juan in early July.

Re-entry has been hard.

Hernández finds the “social decline” of Puerto Rico since Maria disturbing, citing an increase in crime and general disorder. She and Caleb had to move several times since returning; at one apartment, she says, a man shot his girlfriend right outside their bedroom. But they’re now in a place that feels stable and, as a result, she and Caleb do too. He is getting the therapies that he needs, and she’s getting a second Masters degree in special education.

A new leader for changing times

Inside a warmly lit room in the back of Chief O’Neill’s pub, a group of people gathered to celebrate. In the front of the room was a band of young people standing on a small stage, performing Carlos Santana’s Oye Como Va to a crowd of over 100 people. The sounds from their trumpets, congas, flutes, and guitars intensified the already palpable excitement in the space. Of the 100 or so gathered here, none of them seemed to be as excited as the person on the microphone, Rossana Rodríguez-Sánchez, who could barely contain her smile while singing.

Photo by Justin Agrelo

Rossana Sánchez

Rodríguez-Sánchez had a lot to be happy about on this brisk Tuesday night in late-February. After months of campaigning to become the alderman of Chicago’s 33rd Ward on the northwest side, she had officially forced the long-time incumbent into a runoff election, set for April 2.

Born in Humacao, Rossana Rodríguez-Sánchez, 39, was among the “economic migrants,” as she puts it, who came to Chicago since the mid-2000s as Puerto Rico’s economic and debt crisis worsened.

Rodríguez-Sánchez was a teacher in Puerto Rico, but left the job after severe budget cuts left her classroom overcrowded and strapped for basic necessities. She was unable to find another job. So in 2009 she moved to Chicago, where she was hired as director of the Albany Park Theater Company, a youth theater in a North Side neighborhood home to immigrants from numerous Latin American, Asian and European countries. She also taught at Pedro Albizu Campos High School run by the Puerto Rican Cultural Center.

“I would have loved to stay” in Puerto Rico, says Rodríguez-Sánchez. “I would have loved to be with my family. But those opportunities were not there. And I really felt like I needed to take care of myself because I was feeling like I was going to collapse emotionally.”

As an avowed socialist with a keen class consciousness and deep roots in the community, she is often referred to as Chicago’s version of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – a comparison she calls “an honor,” while pointing out their differences.

“I grew up in the island and lived there until I was 30,” she says. “Living in a colony gives you a different perspective on U.S. politics.”

For some, Rodríguez-Sánchez symbolizes the diversity of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community, a young leader not based in Humboldt Park or directly representing the city’s long-standing Puerto Rican organizations. She is among the first members of the group the Chicago Boricua Resistance (CBR) – a politically independent group that advocates for the decolonization of Puerto Rico. Founded in 2016 by largely younger and more progressive Puerto Ricans, CBR works outside of the established Puerto Rican insitutitions in Humboldt Park. The group hosts education events around Chicago, motivating people to understand Puerto Rican history and colonialism – history that isn’t widely known in the U.S. Shortly after Hurricane Maria, the group organized an aid brigade to the island.

For Rodríguez-Sánchez, her advocacy work and political run in Chicago continue a life-long devotion to activism.

She went to her first protest when she was six years old, in the town of Humacao where she grew up and her father was a community organizer.

When the river that was her community’s primary water supply was diverted to a nearby U.S. military base during a drought, locals quickly organized and fought to get their water back, as she describes it. The battle for water and her community’s victory was a formative experience that helped shape Rodríguez-Sánchez’ political consciousness.

Through her father’s organizing she met many local activists and socialists, gaining an early awareness of colonialism in Puerto Rico. In high school, she was introduced to the Federación Universitaria Pro Independencia (FUPI), a pro-independence student-led organization at the University of Puerto Rico; and she started a pro-independence organization at her high school with a group of friends. That drew pushback from the administration, she says, who wanted the group to be called a “history club” rather than a political club.

Rodríguez-Sánchez eventually hopes to return to Puerto Rico.

“I always felt that I would go back home and I still feel that,” she says. “That’s something most Puerto Ricans that leave keep in their pocket – ‘at some point I’m going to go back home.’”

In the meantime, she brings to Chicago the same spirit that has helped Puerto Ricans survive the debt crisis, hurricanes and other challenges whether on the island or the mainland.

It’s about “identifying the problems that we have and coming together and trying to figure out how to make it work, and then demanding that the government put resources into that,” she explains.

Camille Erickson contributed reporting.

This story is published as a result of the collaboration between the Center for Investigative Journalism in Puerto Rico and the Medill graduate journalism program at Northwestern University.