Gabriel Hernández is on a stage in front of dozens of investors, entrepreneurs and government of Puerto Rico officials who, on that February 14, 2019, arrived early at the Hotel San Juan in Isla Verde to participate in the Puerto Rico Investment Summit.

He is sitting on the edge of a modern gray armchair, his hands clasped between his knees. He wears a purple tie and looks relaxed. He is going to begin a presentation on the benefits of Act 22 to “Promote the relocation of individual Investors to Puerto Rico,” which is now part of the Tax Incentives Code.

“The most important thing for everyone in this room is that since the beginning of this program [Act 22] we have probably handled more than 600 of these relocations of individuals [investors] to the Island. The benefit of having us here is that we have a lot of experience doing this,” he says in English, as he shares the stage with Edgar Ríos Méndez, a tax attorney at the Pietrantoni Méndez & Alvarez law firm.

At that time, Hernández had been under investigation for nine months by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) of the US Department of the Treasury. He was a partner and head of the tax division of accounting firm BDO Puerto Rico. A 55-year-old Certified Public Accountant known in the financial world as “Gaby,” Hernández was one of the most prominent of the class of intermediaries that was created after the approval in 2012 of Act 22 and of “Act 20 to Promote the Export of Services.”

The special class of middlemen’s who present themselves as experts in Acts 20 and 22 form part of large and small law firms, accounting firms and management agencies, some of which were part of a failed “Qualified Promoters” program of the Department of Economic Development and Commerce (DDEC, in Spanish).

For large law firms, such as Reichard & Escalera, Act 20 and 22 clients are a segment within the tax division and the other legal services they offer. Other smaller law firms, such as Stolberg Attorneys at Law, focus their practice on the benefits of these incentives. The management agencies that have been part of the Qualified Promoters program, such as The 20/22 Act Society and PRelocate, are fully dedicated to the promotion of Acts 20 and 22 and the bureaucratic procedures that their beneficiaries need to follow at local government agencies. Some of these people are also beneficiaries of Acts 20 and 22.

This class of intermediaries includes former officials who, during their position in the government, were involved in the creation, approval or implementation of these laws and who later added to their services the tax incentives those laws offer. .

“When Act 22 was created in 2012, investors had access to the incentives exclusively through large law firms such as Pietrantoni Méndez Alvarez and accounting firms such as BDO,” said Giovanni Méndez, tax attorney and managing member of the firm Global Economic Optimization, in an interview with the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish). Méndez worked for BDO as a consultant on Acts 20 and 22 from 2013 to 2017.

The cost of consulting services on these incentives can range from $3,000 to $16,000 for the initial work, depending on the complexity of the case, and can start from when the first income tax form is filled out, Méndez said.

Qualified Promoters, ‘$499 for a call with the boss’

“Hello, thank you for calling ‘PRelocate.’ Due to exceptionally high interest in relocating to Puerto Rico, we are receiving a large number of telephone calls,,” a male voice on a recording answers in English. PRelocate is dedicated to managing bureaucratic procedures and guiding individuals who move to Puerto Rico to pay less taxes than they pay in the US mainland.

Its main offer is tax exemptions that promote the relocation of individual investors and export services. A 30-minute call under PRelocate‘s “talk to the boss” category costs $499, according to its website.

Headquartered in the Miramar area of San Juan, PRelocate got a tax exemption under Act 20 for the export of services in 2018. The company’s managing partners, Mike Schoenfeld, Samuel Silverman and Travis Lynk, also landed exemptions from Act 22 for the relocation of individual investors the same year. Before moving to Puerto Rico, Schoenfeld and Silverman worked as financial advisers at the Boston Consulting Group firm, and Lynk worked for Accenture.

PRelocate’s managers did not respond to an interview request to better understand the business of moving beneficiaries of tax exemptions to the island.

PRelocate markets itself as an “Official Qualified Promoter.” The government of Puerto Rico created this role in 2015 through the DDEC’s “Regulations for promotion incentives,” under the direction of Alberto Bacó.

The Qualified Promoter would get an incentive of 10% from the corporation’s income tax payments under Act 20. That 10% would go to a special fund established by the Secretary of the Treasury Department called the “Special Fund for the Development of Exports, Services and Promotion.” The qualified promoter could receive up to 75% of the amount collected annually for that special fund. The incentive would be granted for 15 years, according to the regulations.

But the government never paid the incentive. Treasury Secretary Francisco Parés and Senator Juan Zaragoza, who was Treasury Secretary when the incentive was created, did not respond to several attempts by the CPI to get answers on whether that special fund was actually created and why the incentive was never paid. According to the regulations, the Secretary of the Treasury would be responsible for “nurturing the fund.”

“After they took it upon themselves to promote business, the government would pass the ball from the Treasury Department to the Department of Economic Development and [the Qualified Promoter program] stopped working because people weren’t going to invest their time and money if they weren’t getting paid,” Bacó, former secretary of the DDEC and creator of the Qualified Promoter entity, told the CPI.

“I signed up but did nothing, I never served as a promoter. I did it [signed up as a promoter] more for Act 20 companies than Act 22, but I never promoted myself. Because, although it seemed like a robust program at first, it was actually not well designed, and my experience is that the people who had participated, weren’t paid. Lots of people signed up, lawyers, brokers, accountants who could provide their services to Act 20 companies or Act 22 individuals and they didn’t practice it either,” said Nick Pastrana Villafañe, founder of real estate and financial advisory firm San Juan Realty Group. Pastrana Villafañe is also the executive director of the Senate Treasury, Federal Affairs and Fiscal Oversight Commission.

A qualified promoter could have made $100,000 a year for 15 years if a company they served generated at least $40 million in profit, “which there are,” Bacó said. The former secretary of the DDEC explained the program as a privatization of the government’s duty to promote Puerto Rico as a business destination. He added that some of those who were qualified promoters are sons of Act 22 beneficiary investors who moved to Puerto Rico.

“That’s a huge problem. Because then you have qualified promoters who are not CPAs or lawyers, they’re basically marketing firms that see the application process as mere paperwork and don’t serve as a filter to say ‘these are your requirements, this is the law, this is what that you have to comply with’ and there’s no license involved. If I give bad advice, I can be disbarred,” said Méndez, consulting attorney at Global Economic Optimization.

The political pressure of The 20/22 Act Society

The 20/22 Act Society, one of the organizations that registered as a qualified promoter and that groups beneficiaries of these laws, has served as a political pressure group. In June of last year, it announced that it would initiate legal action against the government for the changes introduced to both laws when they were integrated into the Incentives Code.

They opposed the increase of an administrative fee that beneficiaries of those laws pay, from $300 to $5,000. The same month, the House and Senate approved amendments to the Incentive Code so that the increase would apply only prospectively and not to those who had gotten the decrees prior to the signing of the Code, an amendment for which The 20/22 Act Society lobbied.

Robb Rill, a Florida-native hedge fund manager who got an Act 22 decree in 2013 founded the membership-based organization. The same year The Strategic Group PR, LLC (TSG), an investment management firm, was granted an Act 20 decree. According to Rill’s corporate website, most of the recipients of these incentives are hedge funds. They are hedge funds firms that generally operate like boutiques with few employees. The Strategic Funds, a subsidiary of TSG for example, has six employees, all from the United States.

Rill reacted to the accusation against Gabriel Hernández of BDO saying: “I have known Gaby personally for eight years and I cannot imagine that he intentionally crossed the line considering the risk and repercussions of doing so, including but not limited to his freedom and the harm to his reputation, his company and the [Acts 20 and 22] program.”

A federal lawsuit that a company by the name of Next Gen Media filed against the US government in November, showed that the Internal Revenue Service agents who raided the company were seeking information about communications between Next Gen Media and Hernández, The 20/22 Act Society and Jorge Kuilan, who is described in an article as a Rill accountant. Kuilan worked for BDO from 2011 to 2014 and since 2019 he has worked for The Strategic Group, Rill’s firm. In February of this year, Rill criticized the IRS’s announcement that it would carry out massive audits of the beneficiaries of Acts 20 and 22, believing that this action violates the island’s fiscal “autonomy.”

Other qualified promoters include José Manuel Lamboy Rodríguez and Miguel Ángel Boix Rocamora. Lamboy Rodríguez is a legislative adviser in the House of Representatives. Boix Rocamora is a Spanish attorney who is a qualified promoter in Puerto Rico, with an office in Alicante, Spain.

A list of qualified promoters that the DDEC provided to the CPI shows that 32 firms and individuals registered under that program. When asked about the amount of funds that were distributed among the promoters qualified by the incentive established by the 2015 regulations, Carlos Fontán, director of the Tax Incentives Office, said “no money has been disbursed under the previous Qualified Promoter program, nor under the entity of Qualified Promoter under Act 60 [the Incentives Code].” He did not respond to why the incentive was never distributed or if the special fund was created.

Act 60 of 2019, known as the Incentives Code, establishes a new Qualified Promoter program. Under this program, the amount of the incentive to promoters changed from 75% to 50%, for a period of 10 years instead of 15. Nonprofit organization Invest Puerto Rico will be in charge of disbursing the incentive under the new Program.

Invest Puerto Rico’s Chief Operating Officer, Ella Woger Nieves, told the CPI that “the qualified promoter program that existed prior to Act 60 is no longer in effect and the promoters that were previously registered and qualified are no longer active.” The new program will be ready by mid-year, Woger Nieves said.

Plantation economy perpetuated

“The laws are new laws, there’s no getting around that. But the laws were created, and were based on a system that existed and the system that existed was the existing relationship between the United States and with Puerto Rico. A relationship that has existed for over a hundred years and that has taken on its own a distinct personality for the last 60 or so years and that has provided Puerto Rico with the ability to incentivize particular areas,” former DDEC Secretary José Pérez Riera says in a video from 2014, when the statutes were created.

For Sociologist Rocío Zambrana, these laws represent a continuation of the United States’ colonial economic policies, with the difference that now the exemptions are not focused on an industry or corporation, but on the individual.

“It perpetuates what many thinkers of the Caribbean call the plantation economy… The economies that are built to simply exploit and dispossess, that are not really built for the well-being of the communities that live and work in those spaces and their cultural formations. … The eviction of the populations that are here and the attraction of other populations that come not necessarily for community or ecological purposes,” said Zambrana, professor in the Department of Philosophy at Emory College in Atlanta and an expert on issues of coloniality and fiscal debt.

“In Puerto Rico there are obvious racial hierarchies and there is a whole political and economic class that is also creating many firms, bankers and lawyers who benefit. There’s also a whole hierarchy that is internal to the context of Puerto Rico and that has to do with that long history of the two colonizations, first from Spain and then from USA. But you have to spin the fine details, I don’t think it’s necessarily a thing of, ‘Puerto Rico for Puerto Ricans.’ It is not a xenophobic position, it’s those people’s points of view, of the people’s material stances, of who’s being affected, the differences of the impacts at the level of race and gender as well, it’s not just as Puerto Rico versus foreigners who come with exemptions,” said Zambrana, author of the book Colonial Debts: The Case of Puerto Rico.

From government to private intermediaries

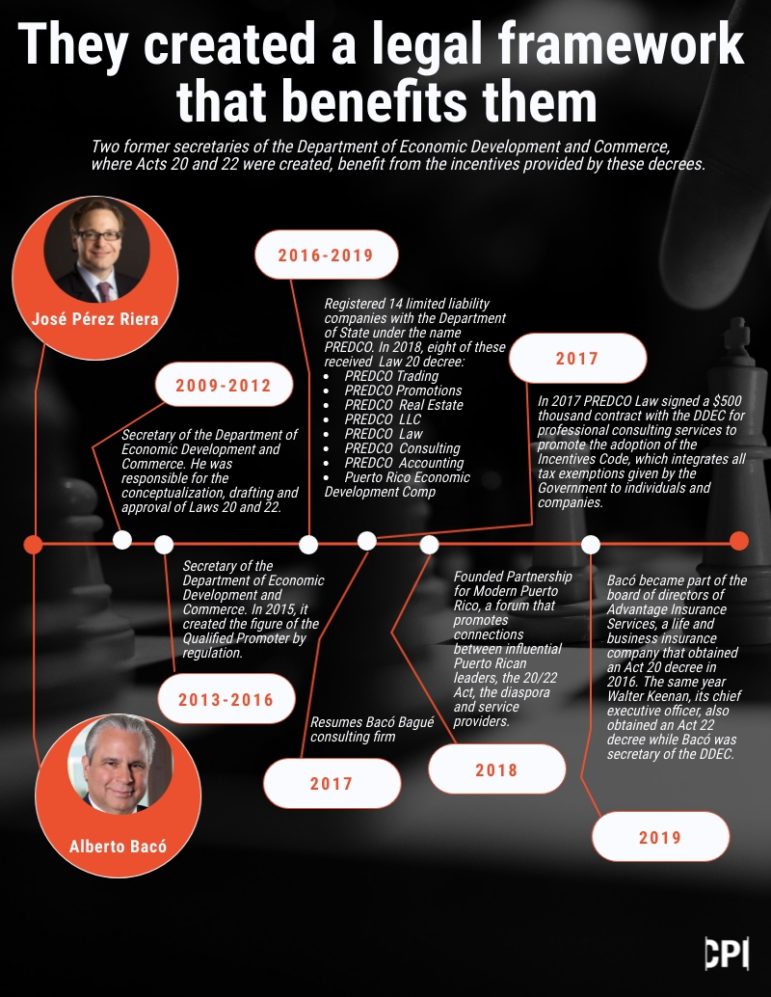

José Pérez Riera was secretary of the DDEC from 2009 until December 2012, during Gov. Luis Fortuño’s administration. In that position, “he was responsible for the conceptualization, drafting and approval of several laws,” including Acts 20 and 22. The DDEC is the department in charge of evaluating and granting requests for tax decrees, which are a sort of contract with which an eligible taxpayer is exempted from paying certain taxes.

After leaving his position at the DDEC, Pérez Riera began a career as a promoter and expert consultant on Acts 20 and 22.

Between 2016 and 2019, three years after leaving his government post, Pérez Riera registered 14 limited liability companies with the State Department under the name PREDCO (Puerto Rico Economic Development Company). Among them are PREDCO Law, PREDCO Consulting, PREDCO Real Estate, PREDCO Promotion, PREDCO Accounting and PREDCO Trading.

Eight of Pérez Riera’s companies landed Act 20 decrees on November 10, 2018. Namely, PREDCO Trading, PREDCO Promotions, PREDCO Real Estate, PREDCO LLC, PREDCO Law, PREDCO Consulting, PREDCO Accounting and Puerto Rico Economic Development Comp LLC.

PREDCO’s main service areas are Acts 20 and 22, according to its website.

In 2017, PREDCO Law signed a $500,000 contract with the DDEC for “professional consulting services to promote the adoption of an Incentives Code,” which includes all the tax exemptions that the government gives to individuals and companies.

“Whether you are looking for business consulting services on Puerto Rico incentives, such as Acts 20 and 22 of 2012, or you are simply looking for investment opportunities, PREDCO offers a unique and convenient one-stop-shop that covers all of our client needs,” says the PREDCO business proposal that Pérez Riera sent to Manuel Laboy, then secretary of the DDEC, and which is included as an attachment to the contract.

The name PREDCO should not be confused with PRIDCO, which stands for the Puerto Rico Industrial Development Company, a public corporation on which the secretaries of the DDEC serve as executive directors.

Since 2016, Pérez Riera’s company has recruited at least eight former officials from different branches of government, such as the Treasury Department and La Fortaleza. Among them, two former DDEC Secretaries, Bartolomé Gamundi and Jorge Silva Puras, and Marcos Rodríguez Ema, former Chief of Staff during Fortuño’s New Progressive Party administration and president of the Government Development Bank in the 1990s during the Pedro Rosselló administration. Rodríguez Ema is Pérez Riera’s uncle.

The current Mayor of San Juan, Miguel Romero Lugo, was also part of the PREDCO team, after having served as Chief of Staff and Labor Department secretary during the Fortuño administration. During his election campaign, between 2019 and 2020, Romero received more than $44,000 in political donations from Act 22 beneficiaries.

Also, on the PREDCO team was George Joyner, executive director of the Housing Finance Authority during the Fortuño administration. In 2017, Joyner was appointed to head the Office of the Commissioner of Financial Institutions (OCIF, in Spanish), an agency responsible for regulating the island’s financial sector, evaluating fraud complaints, and granting International Financial Institution licenses.

“There is no other place where you will be able to have former Secretaries of Economic Development & Commerce of Puerto Rico, former Chiefs of Staff to the Governor of Puerto Rico, former Executive Directors of the Puerto Rico Trade & Export Company, former Executive Directors of the Puerto Rico Industrial Development Company, former Presidents of the Government Development Bank for Puerto Rico, former Secretaries of the Treasury of Puerto Rico, former Directors of the Office of Management and Budget, former Secretaries of Labor or Puerto Rico, former Chief Information Officers of Puerto Rico, former Executive Directors of the Puerto Rico Housing Finance Authority, some of the most well-respected Ph.D.’s in economy in Puerto Rico, and a team of lawyers that are licensed to practice law in Puerto Rico, Florida, New York and Washington, DC, all ready to use their expertise and experience to help you achieve your goals,” the PREDCO website states.

Several attempts to contact Pérez Riera were unsuccessful. No one answers the phone number for their company and the website has already deleted the details of who works there.

In the “About us” section, where the members of a firm are typically listed, there are only two messages endorsing the company, one from Luis Fortuño and the other from former Popular Democratic Party (PPD, in Spanish) Gov. Rafael Hernández Colón.

Alberto Bacó: ‘The preferred local strategic partner’

The secretary who succeeded Pérez Riera, Alberto Bacó Bagué, followed in his footsteps: once he left the public office with which he promoted Acts 20 and 22, he joined the class of intermediaries.

He was secretary of the DDEC between 2013 and 2016. During that period, Acts 20 and 22 gained new momentum as the official economic formula. In 2014, the Puerto Rico Investment Summits began to be celebrated, with appearances by personalities such as investors John Paulson and Nicholas Prouty, who became the main promoters of Puerto Rico as a reduced-tax haven.

Bacó returned to his Bacó Bagué consulting firm in 2017. On his website he describes himself as an expert in Acts 20 and 22, and other incentives that were integrated into Act 60 of 2019.

“Relocating to Puerto Rico under the different available Acts can be a life-changing experience for any adopter. Under Bacó Bagué’s proven and proactive guidance throughout the process, this transition can be a smooth and enjoyable one,” according to his website. In 2018, he founded the Partnership for Modern Puerto Rico (PMPR), an organization that describes itself as a think tank for the island’s modernization.

“PMPR creates a forum that promotes lifelong, authentic connections among passionate leaders and influencers from Puerto Rico, Act 20/22, the diaspora and service providers. Our mission is to become a catalyst for change and modernization through co-investment, macro project promotion, deep-dive thought processes, and productive influence through high-level networking,” according to PMPR’s website.

PMPR’s partners are the Ferré Rangel Group, owners of the El Nuevo Día newspaper; Paulson & Co., a company owned by one of the first investors to adopt Act 22, John Paulson; Grant Thorton, an accounting firm with a division dedicated to government incentives consulting; and PRISA Group, developer of the Dorado Beach luxury housing complex, where many of Act 22 beneficiaries have bought properties. Its president and founder, Federico Stubbe, recently said that if Puerto Rico loses the incentives of Act 60, the island would become a “ghetto.” Other PMPR partners are Evertec and Advantage Insurance Services.

Advantage Insurance Services, a commercial and life insurance company headquartered in San Juan with offices in the United States and the Cayman Islands, obtained an Act 20 decree in 2016. The same year Walter Keenan, its CEO, obtained an Act 22 decree, while Bacó was secretary of the DDEC. In 2019, Bacó joined the Advantage Insurance Services’ board of directors.

Law firms, the usual intermediaries

Puerto Rico’s large law firms, which have always had a tax exemption consulting division, added the Acts 20 and 22 incentives to their portfolio of services. Among them are Pietrantoni Méndez & Alvarez (PMA), Ferraiuoli LLC and Reichard & Escalera.

“We do have some people who have decrees under Act 22 because they qualify. But generally, the people that I have under that status are the shareholders who came to start a business here, either under Act 20 or some other provision. And in addition to the corporate work that we do for them, we help them with that process,” said Carlos Serrano, head of Reichard & Escalera tax division in an interview with the CPI.

As for Act 20, he said that it is nothing new and that therefore, it has not made a great difference in his area of work, which is corporate tax law.

“Everything that has been possible under Act 20 since 2012, could be done under Act 73 [Economic Incentives for the Development of Puerto Rico Act] since 2011. We had a clientele that came precisely to set up those types of units, regardless of whether Act 20 existed,” Serrano said.

“The promotional effort that was given to Act 20 did generate more interest and perhaps, yes, there were people who would never have looked to Puerto Rico for such activities,” he added.

But he also mentioned that many of the companies benefiting from Act 20 were already operating in Puerto Rico before that law was signed. Among those companies are legal firms Ferraiuoli LLC, which secured an Act 20 decree in 2013, and PMA, which was granted one in 2014. The Populicom marketing firm, which has had a decree since 2014, was incorporated, according to the State Department, in 1998, the CPI confirmed.

Meanwhile, to encourage the relocation of individual investors to Puerto Rico, Act 22 did create a new profile of exempt people, said Serrano, who was deputy secretary of internal collections at the Treasury Department, where he was responsible for the 2006 tax reform proposal and the implementation of the Sales and Use Tax.

Edgar Río Méndez, a PMA tax specialist, did not respond to a request for an interview from the CPI. Meanwhile, Pedro P. Notario Toll, head of Ferraiuoli’s tax division, did not want to be interviewed regarding the evolution of the market of clients interested in incentives to relocate investors and export services since these exemptions were created in 2012.

The Stolberg Law firm was granted an Act 20 decree in 2014 and focuses its practice around the incentives of that law and Act 22.

“Having offices in New York and San Juan, Puerto Rico, Stolberg Law advises companies, investors and high-net-worth individuals, both foreign and domestic, on the benefits of relocating their businesses to Puerto Rico under the myriad of world-class tax incentives currently being offered in the Commonwealth,” according to its website. Its founder, corporate attorney Juan Carlos Stolberg, also operates the Upside Management real estate firm in San Juan.

DLA Piper, a British-American law firm with a presence in 40 countries, opened an office in Puerto Rico in 2016. One of the first columns its website published was titled “Puerto Rico’s Acts 20 and 22 — Key Tax Benefits.” The column’s co-author, Manuel López Zambrana, was an advisor to the Government Development Bank, and more recently, to the Treasury Department. In the description of his services, he includes advising clients to obtain tax incentives, including those under Acts 20 and 22.

In 2017, DLA Piper published on tax incentives manual authored by Zambrana and Camille Álvarez, an associate of DLA Piper, which names among its services assisting clients interested in incentives for investors and export services, and who has experience as advisor to the government on the “disbursement and granting of tax credits under several tax incentives.” DLA Piper Puerto Rico obtained an Act 20 decree in 2016.

BDO: From dreams of growth, to complete collapse

In several media outlets, Gabriel Hernández from BDO was described as one of the “founders” of Act 22. Although he was rather a godfather of incentives and a pioneer in the special class of intermediaries. In June 2012, six months after Act 22 was signed, the accounting firm Scherrer Hernández & Co., of which Hernández was a co-founder, joined the BDO International global network. The firm expected to increase its billings from $14 million to $20 million in five years.

Since 2014, Hernández has not missed a single Puerto Rico Investment Summit, where he appeared almost always accompanied by Edgar Ríos Méndez from the Pietrantoni Méndez & Álvarez law firm. Together they made promotional videos on their presentations.

“Basically, what I want to do here is present you with a typical case,” Hernández tells the 2019 Investment Summit audience. “For example, someone calls and says, ‘I heard about Puerto Rico as an opportunity for tax incentives.’ How are these projects typically developed? … The typical structure day one looks like this: we have the orders, the shareholders who want to establish themselves in Puerto Rico. Generally, we have affiliates from the United States and establish a commercial LLC [Limited Liability Company] that initially manages commercial activities in the United States from Puerto Rico.”

Nine months after that presentation, on the morning of October 21, 2020, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents arrested Hernández, after a Grand Jury indicted him on nine counts of fraud. In a separate case, Fernando Scherrer, a senior partner at the firm, was indicted in 2019 for an alleged $13 million fraud scheme against the Department of Education in which Julia Keleher, a former Secretary of Education, was also indicted. In January 2021, BDO International announced its split from BDO Puerto Rico.

Part of the scheme that Hernández was accused of includes providing false information about one of his clients to the DDEC and Treasury to get him an Act 20 decree for the export of services. For the same client, Hernández created an LLC at the Puerto Rico Department of State, following the process he explained during the Investment Summit.

The false information that Hernández allegedly used to fill out government documents sought to pass off $500,000 generated in the United States as if they were the product of business dealings carried out in Puerto Rico, making them tax-free. This time, Hernández’s client turned out to be an undercover IRS special agent posing as a wealthy Arizona investor, according to the indictment dated October 14, 2020.

Hernández has pleaded not guilty to the charges and is awaiting trial.