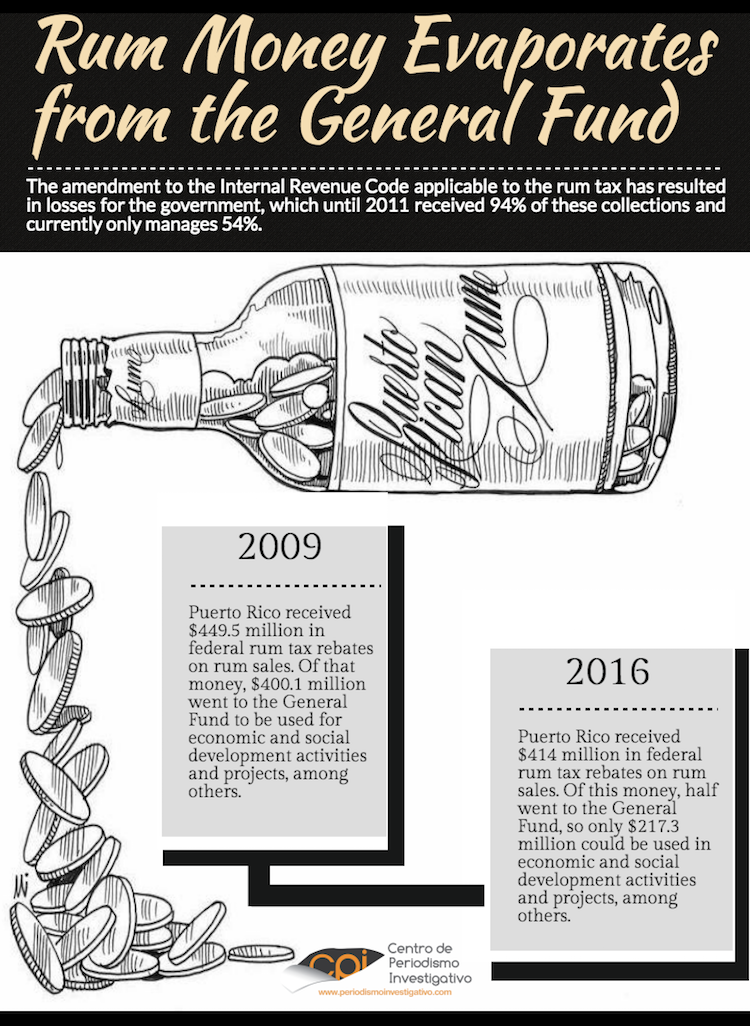

The government of Puerto Rico has missed out on $434 million in revenue since 2011 by changing the rules of the game regarding how rum tax rebates are distributed. The amendments done to the Internal Revenue Code under the Luis Fortuño administration increased the rebates rum producers receive from a maximum of 10% to 46%, which has undermined the General Fund that used to receive that money and used it for economic development projects.

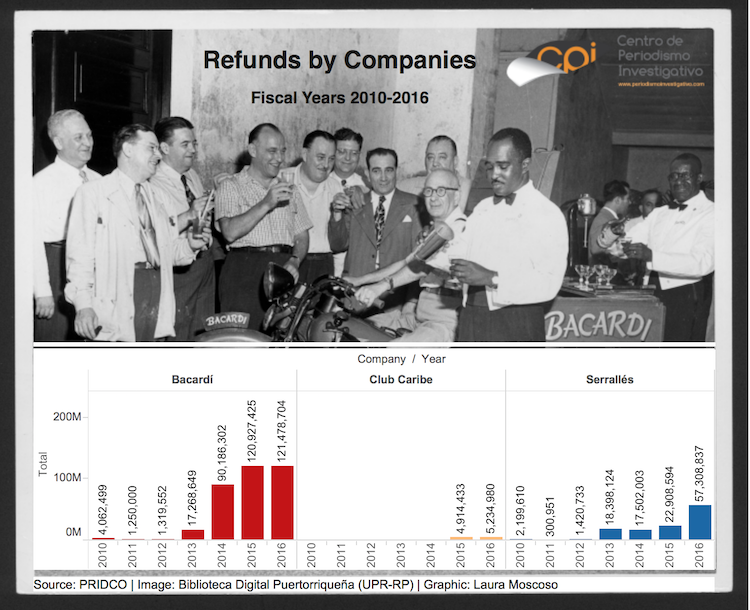

Since then, the distribution is done by sales volume and lines the pockets of big rum companies such as Bacardí, which takes the biggest chunk of the rebate as the world’s principal rum producer. Since fiscal 2011 to July 2016, that company has received $359.6 million of the amount the U.S. Treasury reimburses Puerto Rico for the tax on rum produced on the island and sold to the U.S. mainland. Bacardi has not created more jobs in Puerto Rico after receiving this additional incentive, a company executive conceded.

In the last six fiscal years, the government has transferred $554.8 million to three rum producing companies in Puerto Rico, related to the rebate the island receives on taxes for rum sold in the United States. Most of the money has gone to Bacardí’s pockets, a multinational company that has 27 facilities in 16 markets on four continents. Bacardí is the world’s largest rum producer with sales of that and other liquors in more than 150 countries.

But it wasn’t always that way. Until 2009, Puerto Rico used approximately 94% of that money to support economic development on the island. That fiscal year, according to data from the Treasury Department’s Economic and Financial Affairs Office, Puerto Rico received a total of $449.5 million in federal rum tax rebates, of which it allocated $17.3 million to the Puerto Rico Conservation Trust and $5 million to the Science and Technology Trust. Another $400.1 million went to the General Fund for regular government expenses and capital improvements. Only $27.3 million were granted as incentives to the rum industry. That subsidy was mostly to support marketing and promoting efforts for the product.

However, the government decided to amend the way the funds from that rebate were distributed, sacrificing about 40% of the money received from the tax on local rum sold in the U.S. mainland. Those changes were done in an attempt to match the juicy incentives that the government of the U.S. Virgin Islands began granting in 2007 to the same sector.

The Center for Investigative Journalism found that, six years after the changes, not only have $434 million been sacrificed at the expense of the General Fund, but that in the midst of an almost decade-long economic recession, the rum industry shows an 11% increase in Puerto Rico, but pays 18% less in taxes to the government.

Background of the federal rum tax rebate

Since 1917, Puerto Rico has participated in the federal rum rebate tax program, a public policy of financial support and agroindustrial development for the production of rum and the sugar industry. In 1954, Congress extended the rebate to the U.S. Virgin Islands, with the purpose of helping Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands financially to provide essential public services and develop infrastructure projects.

The math is as follows: for every $13.50 in excise taxes per gallon produced in a territory and sold stateside, $13.25 is reimbursed to the territory. Of that amount, $10.50 are authorized permanently by law, while the remaining $2.75 must be authorized periodically by Congress through legislation. Therefore, the more rum a territory produces and sells to the U.S. mainland, the more funds that territory’s government receives.

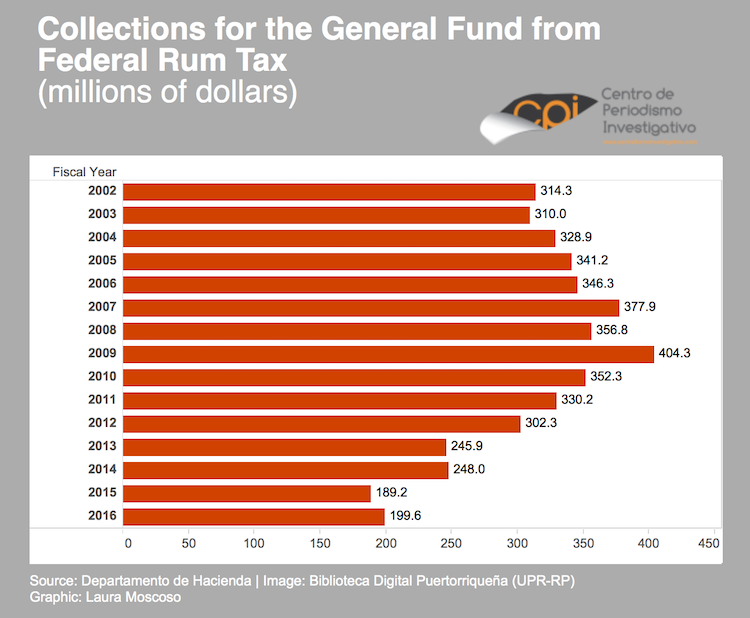

Through the program, the Puerto Rico General Fund received an annual average of $348 million from rum shipments between 2002 and 2010. According to the official report from the Treasury Department, under the heading of Net Income to the Federal General Fund, that annual average has decreased to $252 million from 2011 to 2016. This period, which includes the years since the increase in the reimbursement received by the distilleries came into force, reflects a 27% decrease in what the government adds to the general fund for the reimbursement.

Rum wars

In 2008, the announced exit of Captain Morgan from Puerto Rico set off the panic button. Diageo, the parent company of the rum that is the second highest-seller in the United States and was manufactured by Serrallés in Puerto Rico, announced it would move production to the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The agreement between the government of the U.S. Virgin Islands and Diageo was signed June 17, 2008. The agreement would provoke, starting in 2012, the loss of $136 million annually of the rum tax rebate, equal to 31.4% of the revenue Puerto Rico received under that heading. The agreement between the U.S. Virgin Islands and Diageo to transfer Captain Morgan’s operations to that territory was too attractive for other firms. Diageo would receive direct subsidies and other incentives, including the construction of a rum production plant amounting to about 50% of the new income from the federal tax the U.S. Virgin Islands would receive as a result of Diageo’s relocation. On November 23, 2010 it announced the opening of its distillery in St. Croix.

Those incentives would be paid with the federal funds the government of the U.S. Virgin Islands receives from the federal rum tax rebate, former Resident Commissioner in Washington, Pedro Pierluisi, told the Center for Investigative Journalism. Pierluisi presented several bills in Congress between 2009 and 2011 to impose caps on the incentives that territories could offer to companies from the rum tax rebate.

Pierluisi said the initiatives did not prosper because of strong lobbying that provoked Congressional inaction. In that context, the government of Puerto Rico approved in 2011 amendments to the Internal Revenue law increasing from 10% to 46% what the brands participating in the Puerto Rico Rums Program received directly from that money.

“The bills did not move forward in the legislative process given mostly to the opposition by the government of the U.S. Virgin Island and Diageo. The agreement had a predictable result, setting off a competition (between territories) to spend the funds. That is not ideal, but I do not see the federal government or the territorial governments taking any measures to change this in the near future,” Pierluisi said.

An analysis of the effect of those amendments to the Internal Revenue Code conducted by economist Ramón Cao confirms that the changes in the distribution of the rum tax rebate have not resulted in sound business for the governments of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands; the liquor companies have won. Cao said the inaction in Congress to regulate the way the territories distribute the rebate did not give the government of Puerto Rico another way out, walking into the trap to attract or maintain the rum industry in exchange for sharing the money the federal government reimburses.

“Those incentives are a bad idea; the ideal thing would have been for the federal government to impose rules; but it decided to look the other way, which provoked a change in the rules of the game. It is a zero-sum game where in the end the players are worse off because those who benefit are the industries that take the money that is supposed to be used to repair roads, build hospitals and pay the teachers, which are the things a government should do,” Cao said.

Through initiatives such as Law 148 of 2014, which earmarks a maximum of $10 million for marketing through the Rums Program, the opening in 2013 of the third distillery — Club Caribe Distillers, LLC — negotiations with Serrallés to increase its rum production along with a bill to harvest sugarcane to substitute that distillery’s imports of molasses, the government has sought to recuperate the rebate money lost with Captain Morgan’s exit.

However, the money barely reaches the government’s coffers. Since the approval of the amendments to increase the funds that rum companies receive, the island gets more money each year from the rebate, but puts less into the General Fund. For example, in 2009, under the same distribution formula, the government was able to deposit into the General Fund $400 million of the $449 million received. Meanwhile, in 2016, although the federal government reimbursed $414 million, Puerto Rico deposited only half (about $200 million) into the government’s coffers, because of the increase in the amount of funding that goes directly to the distilleries.

According to the Planning Board’s Statistical Appendix, in the last five years the rum industry in Puerto Rico has grown by 11%, but its contributions to the General Fund during that same period have dropped by 18%.

“In other words, they produce more but pay fewer taxes,” said Dr. José Caraballo-Cueto. According to the economist, although it was necessary to improve the agreements with the rum companies in Puerto Rico, the government should not have been so generous because it is a way to unconditionally subsidize that sector.

“They should have been given special treatment given the circumstances, but it should have been in exchange for something. I believe there has to be a more precise methodology than just their threat to leave. What has happened is that they are given the subsidy in exchange for nothing. They’re not being told they need to create a certain number of jobs, or buy intermediate products in Puerto Rico,” Caraballo said.

He criticized that in Puerto Rico incentives are granted without rigor, which along the way become corporate maintenance, since they are not tied to production growth or to job creation.

Former Treasury Secretary Juan Zaragoza agreed that the problem of granting incentives is that the government does not measure their cost and effectiveness periodically. He said it should be required by law that studies are conducted every five years to measure the impact of each incentive the government grants.

“A study must be done that measures how much the government has stopped receiving; What the benefits have been; If the mechanics of distribution are justified and what has been the impact on the industry… That is the great defect of the incentives; that they are not evaluated periodically. They have to be reviewed,” he insisted.

In the coming months, the government will review these incentives as part of the establishment of an Incentive Code to review, amend or eliminate agreements that do not bring benefits to the island.

The Treasury Department and the Department of Economic Development and Commerce have already begun the revision process.

“I think we have to look at everything and see what effectiveness it has for the island…Any revenue source that depends on incentives [must be] analyzed, and this is one of them,” Raúl Maldonado, the new Treasury Secretary told the Center for Investigative Journalism.

The big multinationals eat up the small locals; the more they sell, the more they receive

The amendments to the Internal Revenue Code of 2011 not only increased the amount of money received by the rum producers, but also made it possible for that money to be distributed according to the company’s sales volume, which directly benefits the large producers compared to small local distilleries.

The main beneficiary is Bacardí, a company with annual assets of more than $3 billion. In Puerto Rico, that company produces 83% of the rum sold worldwide.

“In response to the questions of whether we could operate without the rebate, I think so,” said Eduardo Vallado-Moreno, regional vice president of Bacardí’s supply and manufacturing chain for the Americas.

“[The rebate] is important, but half of that 83% does not receive the benefit of that reimbursement because it does not reach the U.S. Even without the excise tax, we would be in Puerto Rico. The changes done to the rebate to the U.S. Virgin Islands forced us to meet with the government of Puerto Rico and seek and agreement. With the government’s support, we reached an agreement that could be said eliminated the competitive disadvantage with the U.S. Virgin Islands. We had no intention of leaving Puerto Rico, but the changes prevented the operations from being affected by the unfair competition posed by the attractive incentives offered by the U.S. Virgin Islands to rum producers,” Vallado said.

Bacardí uses the reimbursement for marketing and production in Puerto Rico, he said. In recent years, the company has invested nearly $120 million in the modernization and renovation of facilities on the island, with the construction of three additional aging cellars, rebuilding the rums mixing area by adding more tanks, and building a new laboratory, said Vallado. He also admitted that they have not increased their workforce despite receiving more annual funds after the increase in the reimbursement.