They changed schools three times in three years. That is what Zadiel and David’s education has been like. The first lives in Sabana Grande in the southern region, and had to move from the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo school to the Segunda Unidad David Antongiorgi Córdova. Now he takes online classes as a student in the Santiago Rivera Vocational School in Yauco. The latter lives in San Juan in the North, and his migration has been from the Sofía Rexach School to the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas school, to the Manuel Elzaburu y Vizcarrondo School, where he is enrolled in elementary level of the Montessori method .

Zadiel and David, 14 and 9 years old, respectively, are part of the educational communities that have experienced the effects of the school closure policy promoted during the last decade by different administrations in the Department of Education (DE), due to the structural damage by Hurricane María in 2017 and the earthquakes in early 2020. Now they have to deal with distance learning because of the coronavirus pandemic without access to immediate or temporary solutions due to the technology gap.

Meanwhile, a new administration will take over the Department in January 2021 without a plan aimed to address the lag and emotional needs of school communities, and with hundreds of schools lacking proper maintenance or repairs after the damages caused by the earthquakes.

Just three years ago, Zadiel, along with 159 other students from the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo elementary school in Sabana Grande had to move to the Segunda Unidad David Antongiorgi Córdova school because the damage caused by Hurricane María forced the DE to close the school. They can’t go back to the second school after it was classified as an unfit structure due to earthquake-induced damage.

The school community that teaches the Montessori method in the Cantera sector of San Juan is facing a similar scenario. In early 2018, while using the Sofía Rexach school, they learned that they would be transferred to the Manuel Elzaburu y Vizcarrondo school. Although they would have more space there for their growing enrollment, the latter school needed repairs after Hurricane María, so most of the students remained at the Sofía Rexach school while five groups studied in interlocking at the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas school. The move became official in September 2019. A year later, the Sofía Rexach school building was donated to the Corporation for the Integral Development of the Cantera Peninsula.

“They had us under those conditions for a year. We went to public hearings to see what was going to happen, because everyone was to blame but no one took responsibility for what was happening with our school. Nobody would formally meet with the principal,” said Tatiana Santiago, who is a guide, as teachers are identified in the Montessori philosophy.

Three months later, the 306 students from the Elzaburu y Vizcarrondo school had to move to the facilities of the Boys & Girls Club organization at the Las Margaritas public housing complex after their school was classified as unfit following the earthquakes. The foundation of an exterior column of the main building is corroded and puts the structure at risk, they were told.

School director José De Jesús Pérez said, “the corrosion of these beams has nothing to do with the tremors. It’s a lack of maintenance.”

School communities have questioned the classification of campuses as a result of post-disaster inspections, either because of the inaccurate nature of the damages pointed out to justify closures or, in the case of the earthquakes, because they were done in a hurry and superficially, bypassing the evaluation of the structures’ earthquake resistance.

The post-hurricane María inspection of the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo elementary school in Sabana Grande is not available among the documents provided by the DE on its website or in files from the Infrastructure Office to corroborate the damages that explain its closure. The move took the faculty by surprise. The students who needed to move between the Vázquez Pueyo School and the Segunda Unidad had no transportation, as teacher Carmen Montalvo recalled.

Photo by Abimael Madina | Center for Investigative Journalism

Classrooms at the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo school in Sabana Grande.

“The government offered them transportation and it was never provided. The parents had to walk from the Susúa [neighborhood] to the Maginas [neighborhood]. They adapted by getting rides,” she said. It’s a 10- to 15-minute car ride between the two schools. Walking can take an hour.

This teacher’s complaint confirms the disadvantages of the poorest students to access transportation or other services, as Economist and Professor José Caraballo Cueto noted in his “Academic achievement and school closings” study in which he affirms that “displaced students had a incidence of poverty 0.037 percentage points higher than non-displaced … it’s a probability that these displaced students are less likely to get transportation or to have resources to support them in their integration into the receiving school.”

Montalvo, who had been teaching at the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo elementary school for 27 years, said that Hurricane María “knocked down trees, but structurally, I didn’t see any damage to justify the school’s closure. We were shocked because we had the school in mint condition.” In contrast, the inspection of the school where she was relocated with her son Zadiel, who was in his last semester of sixth grade, classified two buildings as partially fit due to leaks, damage to the plaster, a cracked column, and corroded steel rods.

“The day school started after (Hurricane) Maria, they called us at six in the morning. They gathered us in the cafeteria and told us, ‘Now you’re part of the David Antongiorgi faculty,’ and we all looked at each other. That’s when we found out that the [Francisco Vázquez Pueyo] school had been closed,” Montalvo said.

Photo by Abimael Medina | Center for Investigative Journalism

Right now the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo school is useless due to lack of maintenance.

Sabana Grande had 10 schools until 2014. But the closure policy promoted by the New Progressive Party (NPP) and the Popular Democratic Party (PDP) administrations, coupled with Hurricane María, left only four schools open. The earthquakes in the southwest reduced them to two partially suitable in that town: the Luis Negrón López and Blanca Malaret schools.

The director of the David Antongiorgi Córdova Elementary and Middle School, Jeannette Torres Santiago, said “the new facility can be made fit for use, but since the ramps for disabled are attached to those old buildings, we’re not allowed to be there over fears that one of those buildings (may) collapse. Since the earthquakes continue, the Department is not going in to do [repair] work.”

The emotional toll of the disasters

“The students who faced Hurricane María when they were in kindergarten are the ones who are in third grade now. The first four years of these children’s [lives] have been extremely difficult,” said Santiago, the guide.

The students in Sabana Grande and San Juan face the loss of their schools, the constant moves and, more recently, the forced isolation due to the pandemic. This distancing from school also keeps them from getting the help and services from psychologists and social workers to process the ongoing changes.

After Hurricane Maria, a sample of 553 students between the ages of five to 17 surveyed for the Instituto del Desarrollo de la Juventud (Youth Development Institute, IDJ in Spanish) study entitled “The Effects of Hurricane María on Puerto Rico’s Children,” found that 23% showed a degree of change in behavior. The most observed change was anxiety, followed by fear, gloom or discouragement, problems concentrating, lack of interest in continuing to study and poor academic performance.

“It is not a sense of loss that happens overnight; there’s a history there. Although we have a season every year when we can be affected by a storm or hurricane, the island’s schools still don’t have an action plan to address this situation. The María event happened, there were schools that couldn’t be used for months, and then the seismic events that haven’t ended. Perhaps what outrages us is that they left the population completely adrift. Then the pandemic hits, and it’s understandable that everyone had to stay at home, but it can’t be an excuse for not having a plan,” said Hilda Rivera Rodríguez, a Ph.D. in Social Work and contributor to the IDJ study.

Torres Santiago recalled how tough the adaptation process was for the students, parents and teachers that she welcomed from the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo school. “I had to start persuading the parents and teachers; they were reluctant. They adapted, but it was tough,” said the woman who has headed the David Antongiorgi Córdova for 21 years.

The students also had their difficulties, said another of the displaced teachers, Luis Aponte. “The kids came in with another uniform; they were identified. The uniform was blue, and they called them the Smurfs, and the kids got upset. There were students who left because they didn’t like the school,” he said.

Zadiel remembered that “it wasn’t easy to connect with the teachers. It’s not the same as being in the school that I had been in since I was a child, but I started to adjust with my friends, until I was able to pull out of it. I cried because I missed school, but I calmed down.”

Nancy Colón has been a social worker at the David Antongiorgi school for a decade and agrees with Aponte and Montalvo that the transition for the students at the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo school was difficult. She also said the transition to any physical space designated by the DE, “can be even worse because [students, parents and teachers] are in fear of the pandemic.”

Rivera Rodríguez recalled the state of mind that teachers and social workers interviewed for the IDJ study saw among their students when they came back to their schools after the hurricane. Although “some schools were not completely ready, they weren’t as they left them, but the joy of reconnecting with their friends, teachers, returning to a familiar and safe place, was more important than anything.”

Anxiety, depression or changes in behavior will resurface in these circumstances of isolation during the pandemic, Rivera Rodríguez said, while warning that the lack of information from the DE on the needs and strengths to continue the at-home educational process will mean more time without addressing the emotional health of students and their families.

“When it was decided to close everything in March, it took the kids and adults by surprise, and at first the children’s anxiety wasn’t evident; today it’s obvious. They don’t have the space to socialize, to play outdoors,” said Santiago, who has managed to connect with almost all of her students.

Luz Navarro recalled her son David’s anxiety while they waited to move into the school grounds that the DE had promised since 2018. “Every time he got up in the morning, he would say to me, ‘ma, are we going to that school again? [Fray Bartolomé de las Casas]?”.

The average academic achievement of students in the public education system has fallen from 2017 to 2019, according to Caraballo Cueto’s research, but for those students displaced from one school to another the outcome was worse. The DE considers the results of the META tests in the subjects of Spanish and mathematics to calculate the percentage of a school’s academic achievement.

“From 2017 to 2019 the average score of the displaced [students] fell by 0.23 points more than that of the non-displaced. After two years, they continued to show a greater decline in their academic performance than their counterparts,” said Caraballo.

The change affected Zadiel’s performance, his mother said. “He was a 4.0 student and when he came to the David Antongiorgi school, he got the first D in his life. The change wasn’t easy. He had to make new friends, because many of his friends went to other schools or to the United States,” said Montalvo.

To address the academic lags caused by the pandemic, the outgoing Secretary of Education, Eligio Hernández Pérez, proposed that a virtual, or face-to-face tutoring program be implemented next semester during extended hours, subsidized with funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, but when the CPI asked, he did not specify how the service would be coordinated or how student needs would be identified.

“With the pandemic, it has been very easy to say ‘stay home’ without conducting strengths and needs studies. That disadvantage that [students] face in their studies affects them emotionally and that will have long-term repercussions. Parents are left with significant economic concerns, the education and the mental health of their child [who may be having] anxiety, depression or suicidal thoughts. Not to mention that we’re also assuming that there’s no violence or other social problems in many of these homes, and there are,” said Rivera Rodríguez.

The Department used part of the Cares Act funds to hire psychologists but has yet to recruit 279 of those professionals. The agency has not explained who will coordinate or how this support service will be provided, either in schools or virtually.

“The concern [of another move] will always be present, even though we’re settled at the Manuel Elzaburu school. Since we already experienced it once, that lingers for a long time until we can once again trust the government’s word,” said Santiago.

Rivera Rodríguez acknowledges that the level of uncertainty the pandemic has posed is traumatic.

“You may find high school students who say ‘I’m not interested [in studying] anymore, I’ve lost the motivation,’ and drop out,” she said, suggesting that Education, as well as the Department of the Family (DF in Spanish), in coordination with the Department of Sports and Recreation (DRD in Spanish), and the Mental Health and Anti-Addiction Services Administration (ASSMCA), develop a “comprehensive plan of how they’re going to address these young people’s concerns,” beyond asking them to “wait.”

Schools lost between abandonment and inertia

The DE has not submitted a repair plan for the 253 schools classified as partially fit and another 53 declared unfit after the earthquakes. In addition, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) confirmed that it has only inspected 79 of 157 schools in the 14 municipalities that have been under state of emergency since January, to approve public assistance funds. According to the FEMA External Affairs officer in Puerto Rico, Juan A. Muñoz, “the inspections were delayed due to COVID-19 restrictions.”

Although the CPI has asked Education twice for a plan for southern-area schools, the agency just provided a schedule of inspections, and said that it is working to relocate school communities “to mobile classrooms (modules or shipping containers) or interlocking schedules, among other options.”

The Infrastructure Financing Authority (AFI in Spanish) opened a bidding process in December that includes the design and construction of a container park to use as schools in Guánica. The DE has not offered guarantees on how it will maintain the physical distance between students and teachers in these structures or when they will open the calls to establish educational areas in Peñuelas and Guayanilla.

“The only one that is being considered suitable now in Sabana Grande is the [Luis Negrón López] vocational high school. If [to face-to-face classes] are re-established in January, they would move us to the Negrón López,” Torres Santiago said.

According to the David Antongiorgi school principal, this year her school has an enrollment of 492 students, who would have to study in interlocking shifts with 701 high school students.

“How is it possible that they take us out of a school that has two levels at most and put us, with such small children, into a four-story high school?” Montalvo questioned, and insisted: “I’m the first who will put up a tent in the yard if I have to, and I’ll teach there. I’m not going to go up to a fourth floor, and have an earthquake happen while I’m with those very young children.”

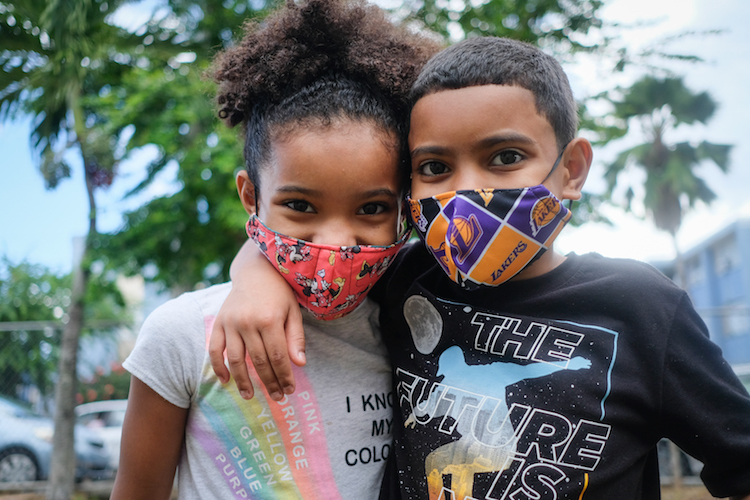

Photo by Nahira Montcourt | Center for Investigative Journalism

Jeirialyz and Jehiel, students at the Manuel Elzaburu y Vizcarrondo school in Cantera, Santurce.

Cleaning protocols are also a factor that generates insecurity among mothers such as Jesmarie Santiago, president of the Parents Association at the Manuel Elzaburu and Vizcarrondo school, who would not send her children Jehiel and Jeirialyz to school even if the agency authorizes their return to the classrooms.

“The semester will start, and cleaning supplies haven’t arrived. Parents are the ones who have to supply the cleaning products, the toilet paper and all those things, because they [the DE] always take too long to provide what the school needs. And if it were cleaned as it should be cleaned, the schools would run out of cleaning products by the middle of the year. What’s the use for the [Education] Department to make a procurement in January and have the products delivered to me in August?” she asked.

Photo by Nahira Montcourt | Center for Investigative Journalism

Jesmarie Santiago and Luz Navarro collect lunches distributed at the Manuel Elzaburu and Vizcarrondo school in Cantera, Santurce. On the right, the school principal, José De Jesús.

She pointed out the damage to the column detected during the inspection in January “and that hasn’t been fixed,” in addition to the lack of maintenance to the schoolyard, which, as she described, “is a jungle.” AFI signed a $489,509 contract with Codom Construction LLC in early September for school repairs, which are to be completed by January 2021.

The abandonment of the Francisco Vázquez Pueyo school for the past three years seems more detrimental than the earthquakes themselves. The one-level buildings have been converted into stables. Sacks with what appeared to be horse feed lie flat in one corner, buckets of water in some corridors, and even a horse saddle sits against a column.

Through one of the gates that is not covered by brush, a coppery-colored mare with a black crest pokes its nose into a bucket. The worn paint on the adjoining two-story building reveals that the third grade classrooms were there. On the side you can see the cracked joint in the staircase to the second floor.

This scenario contrasts with the increase in maintenance spending, $311.7 million between 2017 and 2020 “in part to provide services to closed schools,” says Caraballo Cueto’s investigation, refuting the justification for closing 22 schools, displacing 3,667 students after Hurricane María.

“If they said tomorrow that we’re going to open the schools, it can’t be done because they’ve abandoned them. The building isn’t being properly maintained. [Some schools] were set up for polling stations [during the August primaries], which makes us ask ourselves, how is it possible that schools or cafeterias can’t be opened to provide food, or so that students can go during different schedules, with distancing, to get social and psychological assistance, to seek information? A young man said to me the other day, ‘Why, if we can go to the mall, I can’t spend time at my school?’,” Dr. Rivera Rodríguez said.

Younger students also miss their educational space. A drawn-out ‘yes’ from David’s sister, Jeinyanis, to express her desire to go back to school is overheard while speaking to Navarro, also a member of the school council that Santiago chairs, and who believes that the column identified in the school after the January quakes can be repaired.

“It’s not about the school not being suitable. There are older people here [in Cantera] who tell us that this school is built well, that it holds up. Honestly, as I told my husband a few days ago, if they open the school, the kids will go because I know the teachers I’m counting on,” she said.

With a positivity rate of contagion of 17%, returning to face-to-face classes in January, as suggested by Governor-elect Pedro Pierluisi Urrutia, contradicts the recommendations of health organizations and professionals.

Just two weeks ago, New York City public schools had to close when the positivity rate exceeded 3% for seven consecutive days. In addition, a CPI analysis of official data showed a 781% increase in the transmission of the virus among children and teenagers, in line with the spike in COVID-19 cases in Puerto Rico’s general population.

Zadiel feels he “would not be 100% safe at school,” not so much because of the fear of catching the coronavirus but because of the sequence of quakes that persists in the southern region of the island. “The school I’m in has three levels,” he said about the Santiago Rivera Vocational School in Yauco, where he started the ninth grade in the barber workshop this August, and which was classified partially suitable after the earthquakes.