Friday

At 9:00 a.m., Christopher Acevedo opens his laptop to study at the José M. Lázaro Library, at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras campus. He studies here at least three times a week, traveling by train from Bayamón, where he lives with his grandmother. The journey takes him 30 minutes.

Born 19 years ago in California, Christopher navigates between Spanish and English, instinctively responding in the language he inherited from his Puerto Rican parents. He is studying History at the Faculty of Humanities and plans to pursue a career in Law.

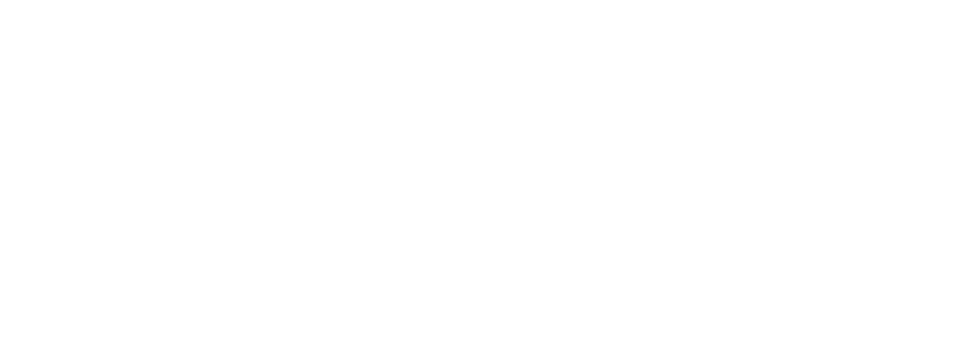

He sits on a blue sofa on the library’s first floor, near the door leading to the Social Sciences and Business Administration faculties, seeking to “escape” the musty smell of the second floor where he used to study.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

“I stopped studying there because of that smell,” he tells me, fingers poised on his laptop keyboard.

It’s Friday, and the library is nearly empty. For Christopher, the Lázaro Library, or simply La Lázaro, as it is affectionately known, is a “center of information and culture” and a significant symbol of the University. However, the deteriorating infrastructure prevented students from entering the building, which was inaugurated in 1953.

“I think it affects many students. There are closed rooms. It’s very bad… I don’t know how to say it, but it’s not fair,” he says.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

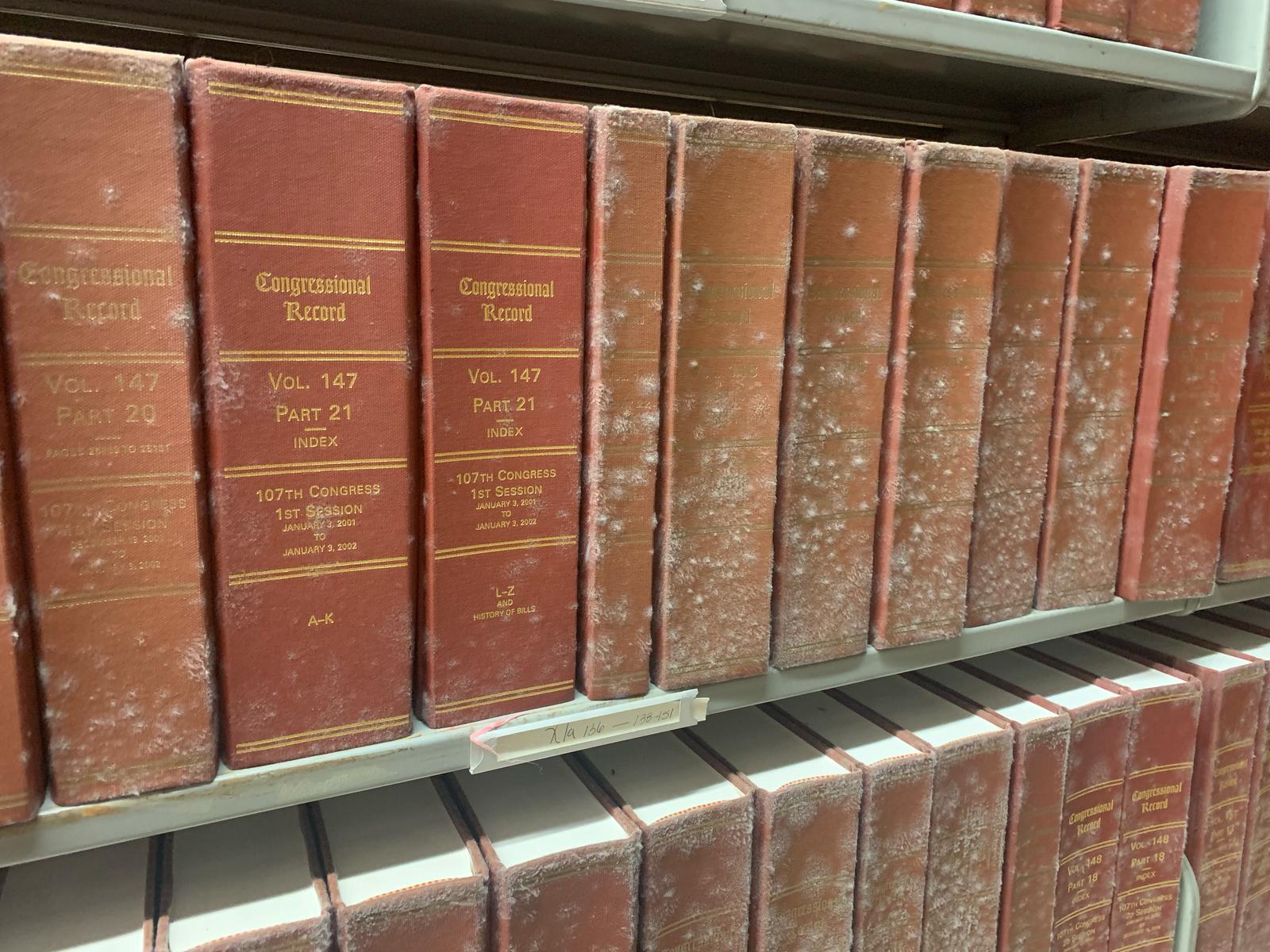

Silence envelops the space for a few seconds until the noise from the library’s back door brings us back to reality. I thank Christopher for his testimony and head upstairs to the second floor. Ahead, a black streak runs down the white wall. The musty smell hits my nose. I climb another floor and find the source of those water lines that dripped from the ceiling. A brown mold stain emerges from a beam, also affecting the ceiling and part of the floor.

In 2021, the university administration announced the completion of the library’s roof waterproofing, which was damaged by Hurricane María in 2017. It was a temporary solution by Tropitech Inc. to stop the leaks, costing $545,229. However, the drops continued to seep from the ceiling because the treatment was not a permanent fix.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

In early March, Astrid Lugo López, president of the General Student Council (CGE, in Spanish) of the campus, spoke with me about the lack of study spaces at the public university and the challenges for students trying to study under increasingly precarious conditions. That conversation, filled with frustration, resonates with me as I walk through the library.

“There are parts in La Lázaro that some students have never seen during their university career,” she said, sitting in the Council’s office at the Student Center.

In the library, which should be a haven for acquiring knowledge, visitors now constantly struggle to find areas not invaded by leaks, mold, and bad odors.

“We need study spaces, and there are fewer and fewer,” the CGE President complained.

The problem has persisted for over a decade, when authorities classified the structure as a “sick” building — a designation tied to issues like poor air circulation, mold, and water damage. Conditions worsened further after the hurricane seven and a half years ago.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

In 2019, I walked the halls of the Lázaro Library to observe the reconstruction process following the damage caused by Hurricane María two years earlier. The cyclone’s wind and rain left deep scars on the building, marks that were still visible two years after it struck, as if the space held on to memories of the disaster.

The damage was evident not only in the library but throughout the campus. The reconstruction works progressed slowly, while the library struggled to heal and regain its place, with trash cans and buckets used to collect leaks and dehumidifiers in the hallways to combat spores.

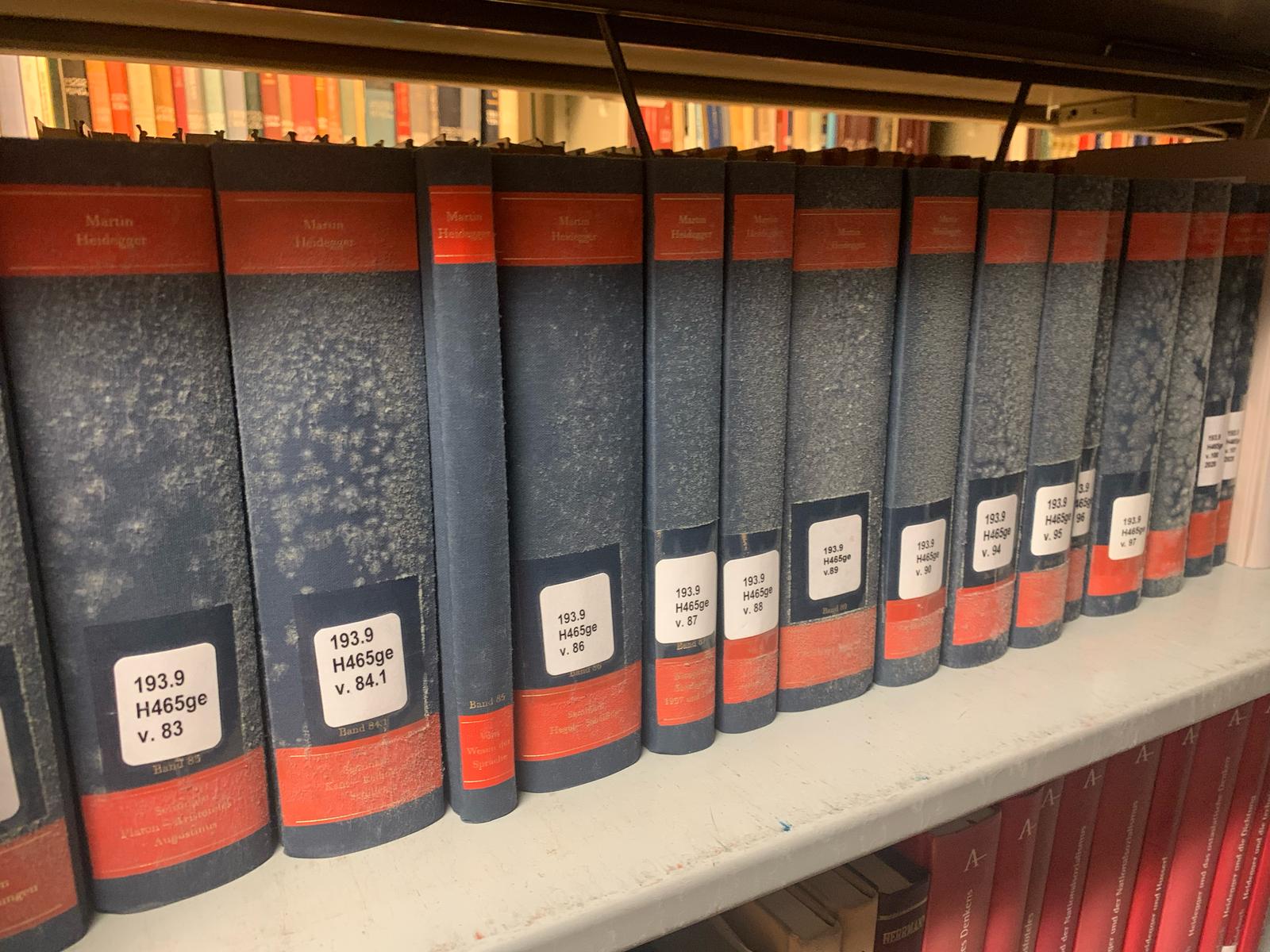

Six years after that visit, some of the deteriorated spaces remain unrepaired. La Lázaro remains, in many aspects, frozen in time. The library operates in a fragmented manner from improvised corners where the different collections were moved.

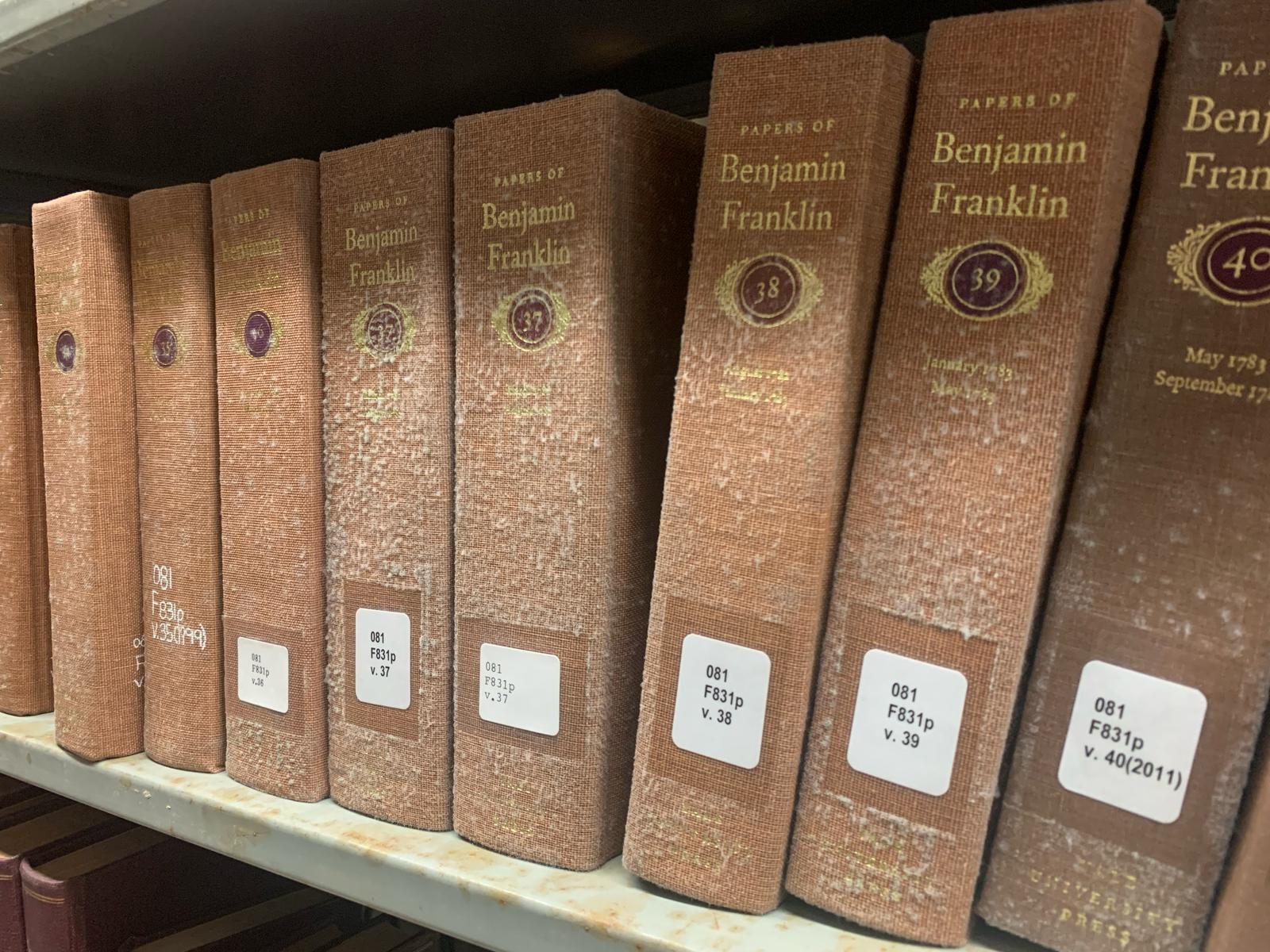

At least seven of the 14 rooms and libraries have remained closed since that fateful September of 2017: Library Services for People with Disabilities, the Zenobia and Juan Ramón Jiménez Room, the Documents and Maps Room, the Film Library, the Library of Library and Information Sciences, part of the Caribbean Regional Library, and the Arts and Music Collection.

Although these collections’ services are offered from other spaces, their operation is not optimal. For example, the Library of Library and Information Sciences, which absorbed the texts from the School of Communication when it merged with the Graduate School of Information Sciences and Technologies to become a faculty, was closed. Currently, the texts can be consulted in the online catalog and picked up in the Circulation Room, where both collections were relocated. The transfer process was lengthy and included exhaustive cataloging and discarding of texts, an employee told me in confidentiality.

“Let’s remember that the public university not only serves the university community. La Lázaro is supposed to be the island’s public library. It’s our national library, and it cannot provide services because entire rooms are closed due to mold and deterioration,” the CGE president said.

Back on the second floor, my gaze falls on two exposed ceiling holes, where leaks reveal their brown mold and white fungus marks.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

I take a few steps forward, and to the left, I encounter the Zenobia and Juan Ramón Jiménez Room, which is dedicated to materials for studying the work of the Andalusian poet and Nobel Prize winner. Two papers taped to the door glass announce that the “area is closed” and that services are relocated next to the Josefina del Toro Fulladosa Collection (Rare Books), also on the second floor.

“Services offered from 8:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.,” the paper warns. The phone numbers and emails included in the notice attempt to fill the void of what is missing: the human presence of those who should be there.

Back on the first floor, glass doors flanked by wooden paneling have also remained closed since 2017. I take a photo and search my phone for the same image I took a few years ago. Little progress has been made in that space that housed library services for people with functional diversity.

Once again, a paper announces that services are on the second floor, behind the Circulation and Reserve Collection. To get there, there are only two options: the stairs or an elevator barely visible a few steps ahead. There are no ramps. On days when the electricity fails — which is frequent in Puerto Rico — an employee who prefers to remain anonymous tells me that only the stairs remain for the 1,179 students with functional diversity or reasonable accommodation registered on campus, according to the institution.

The library, designed by German architect Henry Klumb and inaugurated in 1953 at a cost of $1 million, lacks an interior ramp. Over the years, the building was altered and expanded. Modernity brought air conditioning systems and the urgent need to connect to the internet, but no investment was made in access for people with mobility issues to reach all library spaces. Constant power outages not only prevent some from reaching the second floor but also damage elevators and air conditioners, and temperature fluctuations cause more humidity, which, in turn, promotes mold growth on walls, ceilings, and books.

The ravages of Hurricane Fiona in September 2022 and Storm Ernesto in August 2024 caused asbestos-laced material to detach from the ceiling in the Circulation and Reserve Collection, according to an email from the director of the campus Library System, Nancy Abreu Báez, sent to the director of the Technical Support and Infrastructure Unit, Ramón Canto, which I accessed. The incident prompted the UPR’s Office of Environmental Protection, Health, and Occupational Safety to order the air conditioners to be turned off for cleaning. When the air conditioners were turned back on, they did not cool adequately, allowing mold proliferation to worsen, the report says.

Although the situation was partially neutralized, in her report, Abreu Báez acknowledges in the document that “if temperatures are not stabilized, the mold will resurface.”

Six months after the incident, Abreu Báez tells me that the Library System, which includes La Lázaro, has had the company In-Viro Care conduct deep cleanings of its collections.

Monday

I arrive at 11:00 a.m. in a rush for an appointment at the Río Piedras campus. A weekend separates me from that tour of La Lázaro. At the Chancellor’s Office, I am greeted by architects Mayra Jiménez Montano, special assistant in Infrastructure Affairs, and Jomarly Cruz Galarza, director of the campus’ Physical Planning and Development Office.

Although the agenda was to discuss the campus reconstruction process, the library situation inevitably dominates the conversation.

Both acknowledge the challenges of delays in the restoration works, the complexities of meeting the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) requirements, the labor shortage in Puerto Rico, and an almost endless list of tasks that highlight the restoration’s complexity.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

“When you restore a building, you start from the top down,” explains Jiménez Montano. “That’s why we’re starting with waterproofing. Once the leak problem is addressed, the next phase is the air conditioning systems to assess their condition and install suitable equipment for libraries with humidity controls,” she adds.

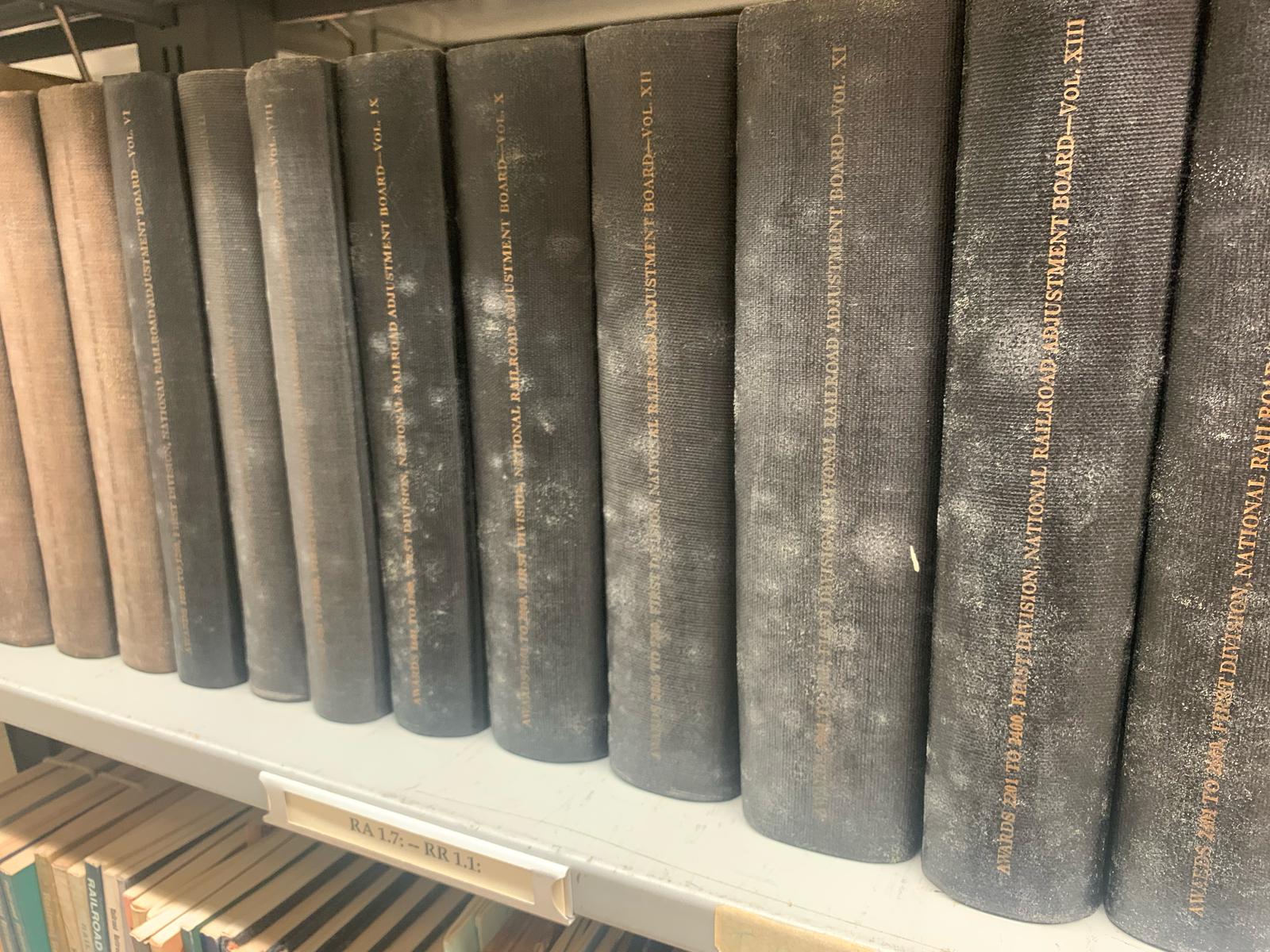

She refers to a new phase of the library reconstruction process, announced last January by the then-president of the UPR, Luis Ferrao. It involves the removal and disposal of the temporary waterproofing system (which cost over $500,000 four years ago) and the installation of a new system in accordance with the 2018 building codes. This phase will cost $3.1 million from FEMA funds and CDBG-DR disaster recovery funds provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The inevitable question lingers: why has so much time passed between the temporary waterproofing, completed in 2021, and the start of this permanent work?

“It must be seen as a very ambitious project. Here alone, it’s $260 million [for the entire campus], but these are processes that must meet each stage and are very rigorous. A competitive process must be carried out, which takes time,” says Jiménez Montano.

“Now, in the last two years, it has moved forward a bit more. Obviously, it’s because we’ve been pressed and have to use the funds, but yes, they are slow processes,” adds the architect, referring to the progression of leaks and the progressive deterioration in the library.

She dismisses the notion that the urgency now arises from instability in the federal government, where President Donald Trump’s policies threaten agencies like FEMA and threaten to cut funds to universities.

She adds another factor: Puerto Rico’s construction challenges, due to the labor shortage and the increase in construction workers’ wages, which rose to $15 per hour for skilled employees.

“Right now, there have been projects, like La Lázaro, where the auction had to be done a second time because there weren’t enough bids. A bidding process can take 60 or 90 days. If it has to be redone because it was vacant, that’s three more months that a project is delayed,” she mentions.

It’s not, then, a matter of missed deadlines, UPR officials assure, but of the inherent complexity of the infrastructure of a historic campus, where every decision and step must be carefully calculated.

Cruz Galarza says the construction had to go through two phases of complex bidding, one for the project design and another for construction, something common in all types of infrastructure development.

“[The design phase] includes aerial photos, humidity studies with thermographic cameras, asbestos and lead studies to confirm that no additional mitigation is required, and making the plans to then hold the bidding process,” adds Cruz Galarza.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The new roof waterproofing, by JC Remodeling, Inc., is just beginning. It will take around 16 months to complete, then move on to the phase of replacing air conditioning systems and, eventually, remodeling the library’s interior, which will include new uses for some rooms. These last two phases are in the design stage by the firm Hacedor: Maker/Architects.

The room that served people with functional diversity on the library’s first floor will no longer serve that purpose. The University Archive will be located there, the architects explain.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

There will not be a specialized room for people requiring accommodation, as the idea, they said, is to adapt all library spaces to be inclusive.

“According to the regulations, all library service spaces must be accessible. Now, rather than designating a closed or isolated space for services for people with functional diversity, we start from the premise that all libraries and all services they offer must be accessible to everyone,” said Jiménez Montano.

In the first-floor Reference Room, however, two booths will be integrated for deaf people to be there with an interpreter.

While all this is happening, the Lázaro Library will remain open, and no further relocations of services or collections are anticipated, the architects estimate.

It’s already noon, and I leave the Chancellor’s Office. Almost without realizing it, I end up in front of the library doors.

The familiarity of the place, with its grand architecture, greets me with no surprises, but this time something in the atmosphere is different: more people are walking inside La Lázaro.

Some go down to clock out for lunch, while others, perhaps out of habit or simple efficiency, cross that first floor from end to end, shortening the campus path, as if the library were nothing more than a shortcut to their route.

This story is made possible through a collaboration between the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo and Open Campus.

This translation was generated with the assistance of AI and thoroughly reviewed by our editorial team to ensure accuracy and clarity.