The wave of corruption that characterized the Ricardo Rosselló-Nevares administration had among its enablers the now outgoing Secretary of Health, Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado, an investigation by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) reveals.

Amid the emergency and deaths related to Hurricane María, a decisive meeting took place at the Government of Puerto Rico’s Emergency Operations Center (COE, in Spanish). Elías Sánchez, lobbyist and former governor Rosselló’s ex-campaign director was present.

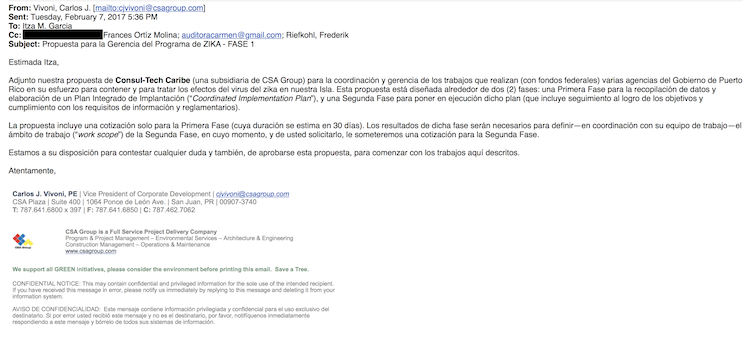

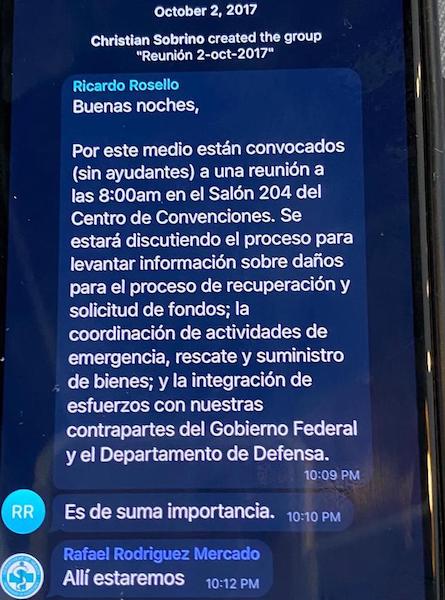

The meeting, held Oct. 2, 2017, two weeks after the storm, was the first sweeping encounter among Government of Puerto Rico cabinet secretaries and federal government response officials. Rosselló called the meeting through a Telegram chat, to discuss recovery, rescue, supplies and funding request efforts. After a brief introduction, the governor left Room 204 of the Puerto Rico Convention Center where the COE was headquartered.

Sánchez, who did not hold any government position, stood up and spoke on Rosselló’s behalf. He delivered two direct orders to two dozen agency heads present: all health matters had to be channeled through Alberto Velázquez-Piñol, a private contractor, representative of the BDO accounting firm, and now a federal defendant; and all federal affairs would be handled through lobbyist Manuel “Manny” Ortiz. They were both in the room.

When Sánchez said that “Alberto is going to handle all Health matters,” some in the room asked themselves, who was Alberto? People linked to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) also asked themselves who Sánchez was and why was he steering the meeting.

The meeting was confirmed to the CPI in separate interviews by three agency heads who were present and who spoke anonymously. Furthermore, the CPI had access to the chat message Rosselló used to summon his agency heads “without assistants” to the meeting.

Photo of text message sent by Ricardo Rosselló on October 2.

Among attendants were the main officials in charge of the island’s health issues, including outgoing Health Secretary Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado. After two and a half years of public health shortcomings and questions from CPI sources regarding his management of the agency, Gov. Wanda Vázquez-Garced cut ties last Friday with Rodríguez-Mercado over her dissatisfaction with the way the former official handled the coronavirus emergency.

Also at the COE meeting was Ángeles “Angie” Ávila, now federally accused, and former director of the Health Services Administration (ASES, in Spanish), who like others accepted Sánchez’s order without hesitation, sources told the CPI. FEMA’s Caribbean Region Director Justo Hernández was also present, sources said.

Hernández evaded answering the question directly of whether he was present at the meeting or at a meeting in which Sánchez had assumed a leading role.

On his behalf, Juan Andrés Muñoz-Torres, director of the FEMA Office of External Affairs in Puerto Rico, answered the CPI’s interview request, saying in writing that at that time “meetings were held daily” at the COE between the Government of Puerto Rico and top FEMA officials, such as Hernández, who was the agency’s alternate coordinator.

“In addition to the FEMA officers, the meetings were attended by then Governor, Ricardo Rosselló, some of his cabinet members, as well as other people invited by the Governor,” he concluded.

Ortiz, who was in the back of the room, allegedly had objections with Sánchez’s order and said, under his breath, that the task should have been handled by the official responsible for official government issues in Washington, Carlos Mercader, then head of the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration. Mercader was not in the room. Ortiz did not respond to an interview request to confirm the information.

Elías Sánchez answered CPI in a written statement saying that “he has never”… “made statements on who should handle what issue in the Government of Puerto Rico or any of its agencies.”

“I have never had any relationship, direct or indirect, with Mr. Alberto Velázquez or Mr. Manny Ortiz, much less, given ‘instructions’ to work on any matters with any of the people mentioned in your question. Neither do I know the tasks which you’re referring to that Mr. Velázquez or Mr. Ortiz performed,” he said.

Photo: Facebook

From left to right: Carlos Mercader, Elías Sánchez, Ricardo Rosselló and Manuel Ortiz.

He added that the statements by the sources are an attempt “by ill-intentioned people to mix my name with subjects and issues that you’re referring to, with which I have absolutely nothing to do.” This statement is not true since there are photos of Sánchez hanging out with Ortiz, published on his Facebook page.

Likewise, his wife Valerie Rodríguez-Erazo acknowledged in separate statements to the CPI that she does know Velázquez-Piñol, although she said she does not have a working relationship with him.

“It’s been a couple of years that I have not socialized with or know from this person,” added Rodríguez.

That wasn’t the only meeting of this sort during the hurricane emergency in which Sánchez, a private citizen and lobbyist for multiple companies, had a prominent participation, almost at the Governor’s level, according to six government officials who participated in the response operation.

On another occasion, for example, Sánchez was sitting next to Rosselló at the head table, one of the sources said. His constant presence in the COE at top-level meetings, they said, was a pattern.

These meetings are an example of the dynamics that had been taking place in the elected Government even before Rosselló was sworn-in on January 2017. In July 2019, the CPI revealed the pressures and influences of Elías Sánchez and others close to the Rosselló administration on core issues and contracts with the Government of Puerto Rico, and their access to privileged information.

Photo: Twitter account of Ricardo Rosselló

Ricardo Rosselló with the lobbyist and friend Elías Sánchez at a meeting of the CEAL, PR chapter on April 18, 2017

Influential people push contracts

The control of the government’s second-largest budget, the Health Department agencies, was put in charge of the former Health Secretary’s Chief of Staff, Mabel Cabeza-Rivera, a friend of Elías Sánchez’s wife, Valerie Rodríguez-Erazo, at least half a dozen sources said.

Rodríguez-Erazo acknowledged that she has been Cabeza-Rivera’s friend “for many years,” but rejected having recommended or influenced her hiring at the agency.

“Neither I nor my husband (Elías Sánchez) had absolutely anything to do with her hiring,” she replied to the question on the matter.

Cabeza-Rivera, who has a bachelor’s degree in marketing and has no experience related to health or administration, has been “the de-facto Secretary” for the past three years, while Dr. Rodríguez-Mercado remained absent, largely tending to patients through his private neurosurgery medical practice. Cabeza-Rivera has handled a good deal of the hiring and contracting efforts at the agency, the sources said.

Photo: Facebook

From left to right: Katherine Erazo, Mabel Cabezas and Valerie Rodríguez

Rodríguez-Mercado’s tenure as Health Secretary has been one of the most criticized in this administration over the poor and disjointed response with which he has overseen the three public health emergencies that Puerto Rico has faced since 2017: the deaths related to Hurricane María, the southern region’s earthquakes, and now the coronavirus. Gov. Vázquez-Garced announced last Friday that Rodríguez-Mercado resigned from his position after her dissatisfaction with his handling of the coronavirus emergency.

Since Hurricane María, sources in the health industry and government officials have told the CPI that they did not understand why Rosselló-Nevares, and then Vázquez-Garced, kept Rodríguez-Mercado in the position. The former Secretary was the one who, as chancellor of the University of Puerto Rico’s Medical Sciences Campus, approved a questionable fast track tenure appointment of Rosselló-Nevares as professor when he was starting his political career.

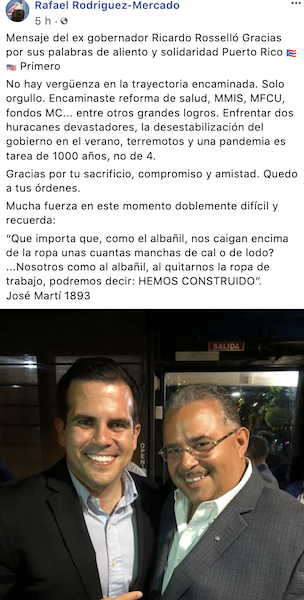

On Saturday morning, hours after the forced resignation, Rodríguez-Mercado published a message of support he got from Rosselló-Nevares on Facebook.

Photo: Facebook

Message from Rosselló Nevares in support of Rodríguez Mercado

Emails and internal documents examined by the CPI confirm the version from sources regarding agency contracting under his watch and identify Cabeza-Rivera as the one placing orders and contracts backed by Velázquez-Piñol, allegedly for Sánchez’s clients, his wife and other close friends of Rosselló-Nevares’ political campaign. The emails show that this modus operandi took place with La Fortaleza’s knowledge and participation in at least half a dozen contracts in the areas of consulting, technology and communications.

Most of the health contracts reviewed by the CPI were signed by Rodríguez-Mercado and the agency’s now acting secretary and then undersecretary Concepción Quiñones de Longo, mother of current Justice Secretary Denisse Longo-Quiñones.

Rodríguez-Mercado declined answering questions on the subject, despite the fact that the CPI insistently has been asking for an interview during the past three months and sent him specific written questions two weeks ago. Among the questions that he did not answer are: What was the need for these contracts in the agency? What was the selection process for these companies and contractors? and specifically, which tasks were done? Cabeza-Rivera didn’t answer questions sent to her by CPI.

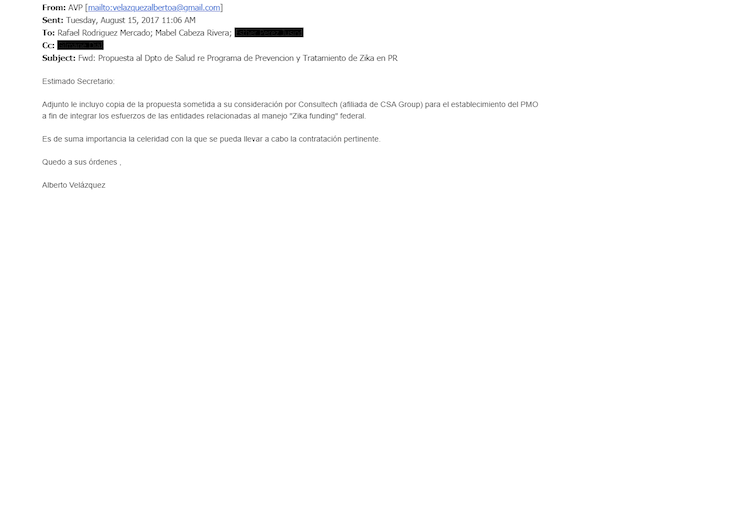

An example of how the agency was run is the contract that Velázquez-Piñol proposed for Consul-Tech Caribe, a subsidiary of the CSA Group, to administer and manage the federal funds for the Zika program in Puerto Rico.

Rosselló had barely been governing for a month, when former Housing Secretary and mentor of his government platform team, Carlos Vivoni, CSA’s vice president of corporate development, presented this and other contracting proposals directly to La Fortaleza. At the Health Department, contracts were channeled through Velázquez-Piñol with Cabeza-Rivera’s authorization and eventually with former Secretary Rodríguez-Mercado’s as well.

On Feb. 7, 2017, Vivoni sent Rossello’s former Deputy Chief of Staff Itza García a two-pronged proposal, signed by CSA President Frederick Riefkohl: (1) Data collection and development of an integrated plan, and (2) execution. Two days later, Rodríguez-Mercado and his team were already discussing the proposal.

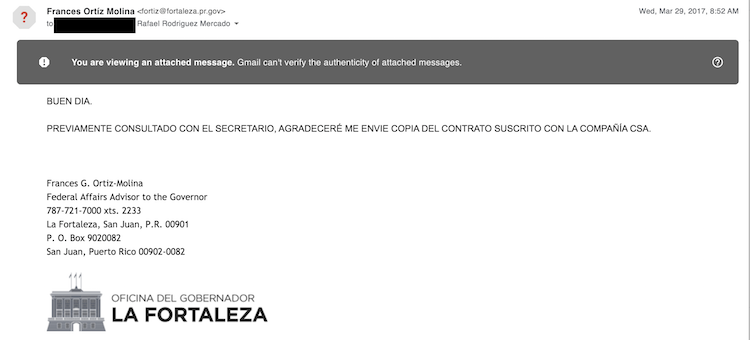

A month later, on Mar. 10, Vivoni sent a revised proposal to Secretary Rodríguez-Mercado and to García, who responded that same day requesting that the contract be fast-tracked.

“Just let me know if you need anything else, it’s important that the project starts as soon as possible,” García said in the message thread.

When asked about this email, where she asked that the Consul-Tech/CSA contract be rushed through, García told the CPI that it was part of her duty to support Frances Ortiz, director of the short-lived Federal Opportunities Center (COF, in Spanish).

She said the COF was part of Rosselló-Nevares’ policy to streamline the process of requesting and obtaining federal funds and one of the priorities of his first 100 days in office, so she used to send this type of email to agencies urging them to collaborate in moving proposals and projects forward. In the email chain that the CPI obtained, this was the only time that García intervened.

Regarding specific questions about the Zika proposal, the former official said she remembers seeing it as a potential pilot project to show the COF’s viability. However, she said she didn’t remember who made the first approach for the presentation of the proposal, whether the company or the government.

She said that after the first quarter of 2017, she didn’t hear anything else about the project and gave up on the COF, due to the pushback to the concept she got from the agencies. She attributed the failure of the initiative to the lack of training and empowerment of public employees in handling it, and the mistaken strategy of transferring responsibilities to private contractors.

She said she was unaware of Sánchez’s alleged relationship with CSA and that at the time, she didn’t know who Velázquez-Piñol was. She began crossing paths with him at the COE during Hurricane María’s emergency.

The emails show how Velázquez-Piñol, who didn’t even have a contract with the Health Department, but was identified in email exchanges with La Fortaleza as the leader of the “Health Task Force”, intervened in core issues at the agency, and urged that the CSA contract be approved quickly despite the fact that there was no Zika outbreak or epidemic on the island. Velázques-Piñol’s contract was with ASES through BDO.

At the time, more than $30 million were available to manage the Zika virus in Puerto Rico, which had to be used before January 2018, according to documents and interviews that the CPI conducted.

“The speed with which the contracting is done is of utmost importance,” Velázquez-Piñol said in an email sent to Rodríguez-Mercado and Cabeza-Rivera.

Personnel from the Puerto Rico and federal Health Departments alerted the Secretary that the data collection and planning work proposed by CSA for the first phase was “easy-to-get” information that could be gathered by the agency itself and that hiring the company was not necessary, according to the emails examined. This type of proposed contracting was also not feasible with federal funding.

“I wanted to reach out to you in response to reports that some officials in Puerto Rico are under the erroneous impression that HHS, CMS and HRSA are requiring that a Performance Management Organization (PMO) be enlisted to manage the Zika Supplemental funds that Puerto Rico receives. Please be advised that no one at HHS, CMS, or HRSA has made that a requirement. Moreover, grant funds cannot be utilized to fund the operation of a PMO. Should you need further clarification, we would be happy to have a conference call with you, Fortaleza and any other representative of the government of Puerto Rico to discuss this matter further”, said Dennis E. González, regional director of the U.S. Department of Health, on Aug. 29, 2017 in an email to Rodríguez-Mercado.

However, Rodríguez-Mercado approved the proposal and ordered that the contract be drawn up, according to a copy of the draft obtained by CPI. For the first phase the company proposed a 30-day analysis that would originally cost $80,000, as established in a copy of the proposal submitted to La Fortaleza in February 2017. The draft contract was for $60,360, given that the remainder would come from the local Department of Labor funds, according to an internal source.

For the second phase of its Zika Fund Management proposal, Consul-Tech Caribe did not estimate costs, according to the document and email exchanges. It only specified that it would act as a backup for the agency in reports generated using “program management” tools. Three sources linked to the project said the cost would be in the millions, because the operation of the tool that Consul-Tech Caribe was recommending depended on the company’s staff feeding the information.

Riefkohl was asked why an estimate for the second phase was not provided, and he responded in writing by sending a different proposal from the one the CPI got, dated Aug. 12, 2017, addressed to former Secretary Rodríguez-Mercado, which estimated the two phases at $150,000.

Half a dozen high-ranking Rosselló administration sources and others close to CSA have assured the CPI that Sánchez was a lobbyist for that company, but Riefkohl denied any type of commercial relationship with the lobbyist.

When initially asked what was the relationship that he had with Sánchez and Velázquez-Piñol, he said, firmly: “None.”

However, when the CPI told him about the emails and confidences obtained, he changed the story. He said they had had a relationship with Velázquez-Piñol as “representative of the Health Department” and “of the government,” and with Sánchez because he “presented our qualifications to him” and said that he had seen him “10 times” in his life.

Why did CSA present its credentials to Sánchez?, CPI asked.

“Because he was the (Rossello’s political) campaign director,” Riefkohl replied.

“We talked to everyone on Ricardo [Rosselló’s] campaign. [Elías Sánchez] also received a presentation from us about our qualifications, about who we were, a Puerto Rican company,” he said.

Although the CPI requested that Vivoni also be present at the interview, he did not attend the meeting because he was not available, according to Riefkohl.

In written statements, Sánchez said he “has never represented any entity to get Health Department contracts,” nor has he mediated in favor of any of the companies with which the sources of this story link him.

He added that “with some” of these companies “he has never” had a professional relationship of any kind” nor does he know them. He also said he currently has no affiliation with any of them. He did not specify which companies he did have connections with in the past.

Riefkohl confirmed that the company had direct access to submitting projects to La Fortaleza and agency heads. However, he said that such access responds to the company’s reputation and the contractual relationships they have had in the agencies for years.

To questions, he said it didn’t seem improper that Vivoni served as a representative in these efforts after having been a key figure in drafting Rosselló’s government platform during the campaign.

The CPI learned that the company also asked to present a proposal in La Fortaleza to provide the Rosselló administration with a technological tool to manage projects across the government. Riefkhol acknowledged that the company submitted the proposal of what he called “a program management tool,” among other things, but insisted that it was the normal course of business for a company.

“We’ve tried to hire Carlos Vivoni for 20 years. He is a professional, he is a trustworthy person, straight forward… (That) he has the contacts and ability to request a meeting with a Chief of Staff, just like anyone has the ability to make a call to the Chief of Staff and request a meeting, and that’s the way it was? We didn’t go there and say, ‘Hey, open the door, we’re going in!’. No, we would call, (and say) we would like to present some ideas that we have, so when could we see the secretary (William) Villafañe, and the deputy (Itza) García, who were there, Ramón (Rosario). We went in early January to present our qualifications, like everybody else, who we are, a Puerto Rican company, to render a service, we have some ideas we can help share to (bring) benefit, we’re a company, we’re a business, of course we want to make money, there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s capitalism. But can we help? That I feel proud to say we can help? Yes. That I can benefit? Yes. That I can do things better than those who came here with briefcases and boots? Yes,” he said.

Regarding CSA’s eight-month insistence on the Zika proposal, Riefkohl responded to the CPI’s questions by saying that it had to do with federal money being available for Zika from the prior administration, which would have been lost, and that this information “was public.”

“[We] saw an opportunity, and a need to save those funds because that money had been granted during the prior administration’s four-year term and it hadn’t been used.. Well, we said, ‘Hey, there’s $40 million … that the government of Puerto Rico should use for the benefit of the people.’ And we saw that there was no traction and that it wasn’t moving and so, (we said) we’re going to help them manage a program, using that money to implement it: pull, push, comply,” he said.

However, the day after the interview, Riefkohl contacted the CPI because he wanted to clarify some of his statements, and sent a letter in which he changed his story and said that La Fortaleza, through federal affairs advisor Frances Ortiz was the one that contacted CSA to request a proposal in the case of Zika, and not vice versa, as he had said in the interview. The CPI has in its possession a proposal signed by Riefkohl, dated Feb. 7, 2017, sent by email to former Chief of Staff Undersecretary Itza García, not to Ortiz, whom he didn’t mention in the interview.

What expertise did CSA have with Zika? the CPI asked.

“(Our expertise is in) managing programs,” Riefkohl replied about conceding that the company had no expertise on the specific health matter.

Is knowledge of the subject not important?, CPI insisted.

“Well, we had handled $7 billion in ARRA (funds). Tools, processes and organization, that’s what is needed. There is no need to know the details. The important skill is having the capacity for execution and leadership. You have to know management, that is: organization, processes and tools,” he said.

Riefkohl said Consul-Tech was established in 2008 by CSA Holdings — parent company of Delaware-based CSA Group — after buying a company by that name in Miami, as a brand-strategy to promote the company’s consulting services that are not related with construction and engineering. These consulting services are specialized in disasters and seeking federal grants, he said.

Ultimately, the Zika contract, which was already in draft, was not signed because Hurricane María hit Sept. 20, 2017 and the priorities changed, as they did for all of Puerto Rico, according to internal sources. Riefkohl said the Health Department never got back to him on the subject.

But six days later, on Sept. 26, in the midst of the emergency, the government signed another contract with Consul-Tech for $800,000, for 90 a day period, through the former Emergency and Disaster Management Agency (AEMEAD, in Spanish) to conduct infrastructure evaluations for different agencies, including the departments of Education and Health.

The contract, which was amended to reach $16.4 million, was canceled abruptly by Gov. Rosselló-Nevares after former Education Secretary and now federal defendant Julia Keleher complained of alleged inconsistencies between structural evaluation reports and the actual conditions described by parents and teachers, Riefkohl said, noting that her judgment was incorrect.

He said his staff conducted a first round of inspections of the schools, and afterwards parents and teachers would make repairs and would send those photos to Keleher making them look bad.

“The Secretary (was) a demanding person, and didn’t like the job or wasn’t satisfied with the job. It only took a call from her to La Fortaleza and the contract was canceled,” he pointed out.

Riefkohl acknowledged that the company is aggressive in its efforts to search for projects and contracts and insisted that these are normal ways in the ordinary course of business. He insisted that the contracts CSA landed, including those of its subsidiary Consul-Tech, respond to the company’s 64 years experience in the construction and management of public projects in Puerto Rico, the United States, and in Latin America, not to their political connections.

Another company that gained VIP access to Rodríguez-Mercado was Jaye Inc., doing business as Telemedik, in association with U.S.-based company GlobalMed. According to documents obtained by the CPI, in the midst of the Hurricane María emergency, the company presented Rodríguez-Mercado with a proposal to create a $45 million telemedicine network for hospitals. The proposal, dated Friday, June 15, 2018, was approved and sent with the secretary’s endorsement to FEMA three days later, on Monday, June 18, according to a letter the CPI obtained. Dr. Joaquín Fernández-Quintero, president of Telemedik, said he did not know why the proposition which he signed, “ended in nothing.”

He said GlobalMed developed the proposal, since Telemedik “doesn’t have the capacity to develop that type of proposal.” However, he declined to specify who got the meeting with Rodríguez-Mercado and who made the presentation. In addition to Fernández, GlobalMed’s representative in Puerto Rico, the proposal is signed by GlobalMed Founder and CEO, Joel E. Barthelemy.

Jaye-Telemedik has landed $516,000 in contracts with the Department of Health under this administration and an additional $2.5 million with the local Social Services Administration.

Another company introduced to the Health Department by those close to Rosselló-Nevares’s political campaign was The Raevis Group, created in May 2016 by John Raevis-Torres, a donor to the Rosselló campaign and former employee of the De La Cruz advertising agency, known for running former Gov. Luis Fortuño’s campaign and for his ties to the New Progressive Party in the past decade.

Raevis’ media buyer is Mari Carmen López, who had the same role in Ricardo Rosselló’s campaign and in his administration through her company Kaizen Media LLC. Kaizen was subcontracted by the companies owned by Rosselló’s publicist and advisor, Edwin Miranda, who is the target of an investigation by the Office of the Special Independent Prosecutor Panel (FEI, in Spanish) along with Rosselló, for their participation in the Telegram chat. In July 2019 CPI revealed the 889 known pages of the chat that led to the resignation of Rosselló and his close circle of advisers.

In response to questions from the CPI about whether Raevis is related in any way to publicist Edwin Miranda or his companies, Raevis-Torres said in written statements that “the company does not have or has had a business relationship” with Miranda. He confirmed he has Kaizen Media under contract “to optimize the negotiation, planning and media purchases for our client portfolio.”

Raevis-Torres did not directly answer the question about who paid the bond so that his firm could start contracting with the government less than a year after its creation. He didn´t answer either how The Raevis Group reached the government and got all of its contracts.

The government requires advertising agencies to pay a bond, which is nothing more than a test of financial capacity given the large investment they have to make to buy advertising space on behalf of the government before the money is reimbursed. The publicist insisted that presently, his company is in “excellent financial condition” and that his company is not used to “disclosing our financial information, or that of our public or private clients, without their consent.”

Kaizen is headquartered in a building owned by Edwin Miranda in Guaynabo, where KOI’s offices used to be. Four advertising industry sources confirmed that Miranda is linked to said company and to Raevis, who has current contracts with Gov. Wanda Vázquez’s administration. Both companies are limited liability companies, so information on owners and officers is not public.

Raevis-Torres told the CPI that he is the sole shareholder of his company. Miranda did not answer questions about the matter texted to his cell phone.

The three sources said that when it was created, Raevis did not have the financial strength that an advertising agency that handles government accounts requires. The company has $23.6 million in contracts with this administration, of which $19 million are linked to agencies under the Health Department’s umbrella, including ASES. Of these, $14.4 million are with the Health Department.

Other large contracts awarded to those close to Rosselló’s trusted advisers in the area of communications are the Health Secretary’s and the agency’s press and communications directors, Peter Quiñones-Feliciano and Eric Perlloni-Ayalón, respectively. The advisers, who handle public communications from their unofficial email accounts, were placed in the Health Department by Carlos Bermúdez-Urbina, Rosselló’s former press adviser and also a member of the Telegram’s WRF chat, three sources indicated.

Both continue to have contracts with Health, and Perlloni, who signs emails as “Director of Communications and Public Health Affairs,” also represents private clients — including a candidate for the Senate for the New Progressive Party and artists — through his company Creactivo Media Solutions. Quiñones has had $360,000 in contracts and Perlloni $317,450 from February 2017 to the present.

Other questionable contracts

Since early on in the administration, Rodríguez-Mercado also awarded multi-million-dollar contracts in the area of consulting and technology to companies with ties to Elías Sánchez and Valerie Rodríguez-Erazo. One of these alleged companies was London Local Services Puerto Rico, a client of Sánchez, according to an internal source, which benefited from almost $1.2 million in contracts over a nine-month period in 2018.

Rodríguez-Mercado was not available to specify what the company was hired for, but the source said that it was hired to do similar work as the one done by Velázquez-Piñol’s in the agency. The London Local contract supports this version since it says they were coming in to do a re-engineering to achieve greater efficiencies in the agency.

The CPI tried to request a reaction from the president and representative of London Local, Francisco Luzio-Ruiz, who has signed contracts on behalf of the company incorporated in September 2016, but the number he has listed was not answered and does not accept messages.

Luzio-Ruiz identifies his residence as being in Dorado Beach East, the same neighborhood that Valerie Rodríguez registered for her company, CDO Group, in her most recent corporation report to the Puerto Rico State Department.

Rodríguez-Erazo, who still has $317,000 in current contracts with the government of Puerto Rico, denied having a relationship with this company and the others mentioned in this story.

Meanwhile, Truenorth Corporation and Microsoft Caribbean, which have been identified by sources and documents as Sánchez’s clients, also obtained contracts with the Health Department. Truenorth obtained 16 contracts and amendments with the agency amounting to $4.4 million for data processing and administration, operation and maintenance services. In Microsoft’s case, the $11.5 million contract was signed by the government Office of Management and Budget for projects at five agencies, including the Health Department.

Truenorth has held more than $57 million in contracts across the government so far in this four-year term. Microsoft’s deals, which have been publicly criticized as excessive and unnecessary by two experts who have served as the government’s Chief IT Officer under two different parties — Giancarlo González and Luis Arocho — total 41 contracts and amendments adding up to more than $123 million.

On the other hand, employee recruitment company Manpower, got $7.5 million in contracts with the Health Department during the Rosselló-Nevares administration. According to two internal sources, Manpower has been used by government administrations of the two main political parties in Puerto Rico — the New Progressive Party and the Popular Democratic Party — to bypass Health’s hiring rules and the Government Ethics Law. This mechanism has allowed bringing family and friends to work at the agency, frequently paying higher salaries than the regular rates.

For example, Lumary Cabeza, Mabel Cabeza’s sister, was placed in the Medicaid Program Office through Manpower, billing more than $70 an hour, according to three sources consulted. The Health Department did not respond to a request for an interview to confirm the information, but Lumary Cabeza’s name appears in official documents representing the agency on behalf of Medicaid and CPI was able to confirm that she currently remains in the agency.

A great deal of Manpower’s contracts are paid with federal funds and, presumably, there are employees hired to work in a certain agency or office, when they really work elsewhere. Manpower Spokeswoman Diandra Fournier did not return the CPI’s call and email for a reaction.

Another contractor involved in Health

In addition to the constant and dominant presence that Velázquez-Piñol had in the Health Department, another private contractor with a great deal of authority participated in official government meetings. The person, identified as Roberto González-Maldonado, has been awarded contracts related to Secretary Rodríguez-Mercado since he was chancellor of the University of Puerto Rico’s Medical Sciences Campus.

Among the people who have expressed concerns about González-Maldonado’s presence in emergency management meetings with government heads during the earthquakes was former Housing Secretary Fernando Gil-Enseñat. Upon leaving his position in January said Gil-Enseñat said he communicated his disagreement with González-Maldonado’s presence in the meetings to Secretary of State Elmer Román.

The CPI tried to reach Gónzalez-Maldonado, but he did not respond to the numbers that appear in his corporate records.

According to the Comptroller’s contracts registry, González-Maldonado — who does business through a company called RA González & Associates LLC — had contracts amounting $173,000 with the Medical Sciences Campus from 2011 to 2012, while Rodríguez-Mercado was chancellor and $76,000 from 2018 to 2019 between the Medical Sciences Campus, the UPR’s Central Administration and the Department of Health.

Rodríguez-Mercado gave González-Maldonado a $10,000 contract at Health for one month, at a rate of $100 an hour, for “legal consulting,” which established that his job was “to help the Secretary with the management and coordination of negotiations with Washington D.C., specifically with Health and Human Services (HHS), Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA), Department of Defense (DOD), Uniformed Services University of the Sciences (USUHS), and other federal and state agencies.”

The contract also says that on a daily basis, he should “require, coordinate, and call different federal employees who handle sensitive issues related to healthcare, the information system, disbursements, especially special fund programs.”

Two sources said González is actually a personal friend of Rodríguez-Mercado and helps him with his contacts to boost his political aspirations.

The cited contracts don’t account for González’s total compensation with the government, given that since 2018 he has also allegedly been working for the Health Department, earning $120,000 annually in a position financed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funds through the Science and Technology Trust.

The Trust confirmed that it is the fiscal agent for a grant awarded by the CDC to fill 109 positions at the Health Department from November 2018 until August 2020, and that González-Maldonado is one of the people who was hired.

However, as of press time, they had not confirmed his salary, duties and expertise for which he was hired. The Health Department is responsible for hiring and supervising these employees, said the Trust.