Although a “sargassum wave” is already visible along Puerto Rico’s coast, which is part of an influx of about 1,100 square miles of algae, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) has not yet identified the funds or completed the technical work to have a sargassum mitigation plan ready on April 3, as required by the legislation signed by Gov. Pedro Pierluisi.

In a written statement sent to the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) on March 14, the DNER did not respond to questions regarding the status of the Mitigation Plan. The agency said it is working on updating its Sargassum Management Protocol created in 2015.

At the CPI’s insistence on the status of the plan, DNER press officer Joel Seijo said, “the plan will be ready by April 3 as required by law.” However, he did not say why the sargassum management protocol has been updated without having the Mitigation Plan.

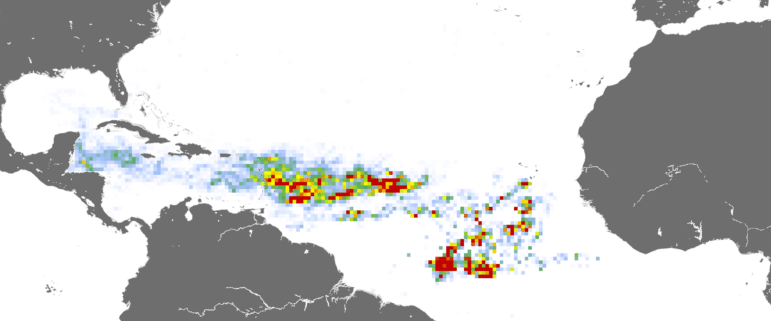

Image provided by Laboratory of Optical Oceanography, College of Marine Sciences, University of South Florida

Joint Resolution 229 unanimously approved by the Legislature in December and signed by the Governor in January 2023, orders the DNER to “include as part of its reconstruction, recovery, and development plans a mitigation plan to address the sargassum problem in our shores.”

The Resolution did not allocate funds to develop the plan and required the DNER to identify state and federal funds. In an interview with the CPI, agency officials acknowledged that they had not identified the funds to carry out the sargassum mitigation plan.

On March 14, a month and a half after that interview, the DNER told the CPI in writing that “DNER personnel continue to identify other funding sources to subsidize the proposed actions.”

The agency was also unable to provide an estimate of how much it will cost to prepare the mitigation plan. The DNER press officer said the agency’s technical staff will draft the plan internally.

The officials who participated in the interview with the CPI were the interim director of the Office of the Coastal Zone Management and Climate Change Program, Cristina Cabrera, the interim secretary of the Conservation and Research division, Farel Velázquez Cancel, and marine biologist and management officer of the Northeast Natural Reserves, Ricardo Colón.

“It’s almost impossible for this plan to be ready in three months. However, the plan we have in the Department leads to that. A working group was established within the Department to, number one, collect all the information we have, and number two, identify the partners or people who can help us,” Velázquez Cancel explained.

Photo by Gabriel López Albarrán | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The lack of a plan and definitive steps coincides with the projection that this summer will be a significant one in the arrivals and accumulation of sargassum for the Caribbean, Chuanmin Hu, professor of optical oceanography of the College of Marine Sciences of the University of the South of Florida, confirmed to the CPI. The scientist, who is an authority on this subject, said the 1,100-square-mile “sargassum wave” that is expected to hit South Florida in June has already floated into Puerto Rico’s southeast coast.

“In the southeastern portion of Puerto Rico, there’s already a lot of sargassum there,” Hu told the CPI. “This will be another major sargassum summer. The northern part of the Caribbean will receive more than the southern part of the Caribbean,” the scientist explained.

Sargassum is a marine macroalgae that covers a large surface area in the North Atlantic known as the Sargasso Sea, and more recently, covers an area that connects the Caribbean, eastern South America, and part of western Africa.

Although this algae represents a valuable habitat for other marine species, its extreme accumulation levels, documented since 2011, have caused an increase in its decomposition. Sargassum rot is what most worries residents and merchants in coastal areas because of the strong odors and the emission of gasses, such as hydrogen sulfide, which put people’s health at risk.

Its decomposition also causes a drop in oxygen levels in seawater and adversely impacts marine life. It also creates shadows on the bottom of the sea because it blocks the sunlight, which results in a lack of oxygenation and an adverse impact on coral ecosystems.

“When you have a pH of 5 and dissolved oxygen at zero, you no longer have a habitat. What you have is a problem,” marine biologist Ricardo Colón warned.

The accumulation of marine algae can generate other problems, like what happened in September 2021: the onset of a sargassum wave on the coasts of Puerto Rico affected power service after the algae got into one of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA)’s Central Aguirre units, clogged the filters, slipped through the pipeline, and left tens of thousands of customers without electricity.

AEE INFORMA | A raíz de un evento de sargazo en las costas de la Isla, esto nos está afectando en las unidades de Aguirre y Palo Seco. Personal está atendiendo la situación. CC1 pic.twitter.com/EYLiWw3iOP

— Autoridad de Energía Eléctrica (@AEEONLINE) September 26, 2021

No equipment to collect the sargassum

Legislation passed in January also orders the DNER to buy the necessary machinery to remove the algae, collect the sargassum, and sift the sand. However, DNER Secretary Anaís Rodríguez Vega said this week on WKAQ-580 AM that this machinery will not be available this summer either, which is when the greatest accumulation of sargassum happens, because it will take about a year for that equipment to get to the island.

Two days later, in written statements sent to the CPI, the DNER said the machinery should be on the island in three or four months. The agency said the equipment was purchased at a cost of $960,000 with funds from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and Fishery Disaster.

In July 2021, the DNER assured the CPI that it was working on proposals to buy equipment with funds from the National Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The agency never explained what happened to that plan. Former DNER Secretary Rafael Machargo also admitted that his agency provided coastal municipalities with these machines to collect sargassum, but he did not know what happened to that equipment or who had it.

Within 90 days — since the law that requires the production of the Mitigation Plan was approved — the DNER was supposed to carry out an investigation process, data analysis, and clear legal aspects, agency officials explained to the CPI.

Foto por Wilma Maldonado Arrigoitía | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

En declaraciones escritas, el DRNA dijo que todavía continúa “el proceso de recopilación de datos en conjunto con la academia”.

In written statements, the DNER said “the data collection process together with academia” is still ongoing.

The DNER appointed a special committee to study the mitigation strategies that — according to the joint resolution — must be included in their reconstruction and recovery plans. The so-called Sargasso Committee is composed of Cabrera, Velázquez, Colón, and the deputy secretary of the DNER Recovery Office, engineer Waldemar Quiles.

“Each location must be considered individually,” said Colón, one of the Committee members, explaining that the type of mitigation proposed will vary depending on the type of the coast because there cannot be a single mitigation strategy.

Hu agreed that any sargassum management mitigation plan must consider regional differences.

“Sargassum is not equal through regions,” the Florida researcher said, while emphasizing that the mitigation resources should not be applied islandwide, but rather in those regions where, aside from getting more sargassum, have a lot of tourist and residential activity.

The plan requires coordination with federal agencies

The DNER officials that the CPI interviewed stressed that the Puerto Rico government’s mitigation strategies must concur with what is established by the Fish and Wildlife Service, the US Army Corps of Engineers, and the NOAA.

The government of Puerto Rico is responsible for manually picking up sargassum on the shore. However, when machinery is required, it must be coordinated with federal agencies, DNER officials explained.

In July 2021, the CPI reported the lack of a public policy from the federal government to manage the extreme accumulation of sargassum in its Caribbean territories, including Puerto Rico. DNER officials confirmed that, currently, this has not changed.

Unlike Puerto Rico, the federal government approved an emergency declaration in July 2022 in the US Virgin Islands, due to the “unprecedented flow of sargassum” and its adverse impact on the waters near a water desalination plant in St. Croix. President Joe Biden signed the emergency declaration.

But in Puerto Rico, when a sargassum event in September 2021 left tens of thousands of people without power, the government of Puerto Rico did not seek a federal emergency declaration as the USVI did.

“This is a complex problem, and we’re trying to find long-term solutions. We’re learning along the way. We chart a course and in implementation, we learn and adjust. And that includes the way in which federal agencies are going to learn from our experiences at the state level,” Colón added.

Cabrera said they will seek advice from the DNER’s Comprehensive Planning division to prepare the mitigation plan.

Meanwhile, under the argument that there’s limited time to submit the mitigation plan, the DNER will not carry out a broad consultation process with representatives of the coastal communities that are most affected by the sargassum buildup.

“Perhaps some kind of meeting can be held on [Microsoft] Teams or write letters, requests for information, to involve the communities,” Cabrera said.

When the CPI asked again a month and a half later about the consultation with the community, the agency responded in writing that “the committee is coordinating meetings with DNER concessionaires in our natural areas, personnel associated with the tourism industry in the area, and the community.”

Since 2015, the DNER has had a response protocol in place to address cases of extreme sargassum buildup and picking up the algae on the beaches. The protocol responded to concerns about large accumulation and decomposition events that happened that year, mainly in areas along Puerto Rico’s eastern region. The protocol does not consider mitigation strategies or proposals to handle sargassum once it accumulates on the shores.

In 2019, the CPI reported that none of the coastal municipalities had included the accumulation of sargassum in their mitigation plan.

Colón said there are areas in Fajardo, on the East coast, that already have a mitigation plan that consists of placing floating barriers, so that sargassum is handled without affecting other marine species of high ecological value.

“We already have a specific plan for Laguna Grande [which is part of the bioluminescent bay] and Las Croabas [in Fajardo] that includes a combination of floating barriers that block the sargassum before it settles,” Colón explained. “The problem is that when it settles it rots and dies there. The purpose of the barriers is to retain it in a place where the flow and depth of the water will keep it alive longer so that it can be handled easier. The barriers have worked very well in other places in the Caribbean,” he assured.

The marine biologist said that the DNER is evaluating — within the mitigation plan that it develops — the option of removing the sargassum in the water and not waiting for it to reach land, decompose and mix with the sand.

Próximo en la serie

2 / 3

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.