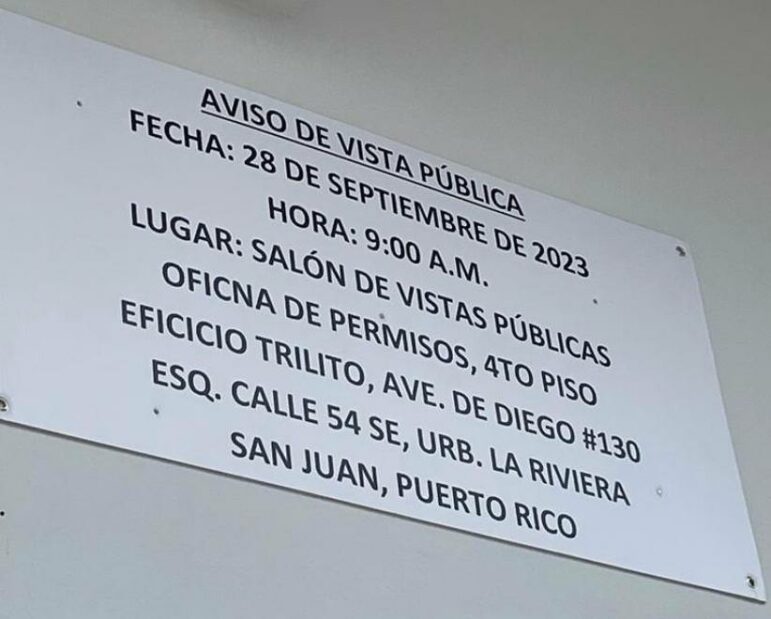

To access the Trilito Building in Puerto Nuevo, where the Municipality of San Juan’s Permit Office is located, you had to turn onto 54 Street more carefully than usual on Thursday morning. On both sides of the road, a row of cars and even a school bus with the phrases “I am Paradiso,” “I am chárter,” “Paradiso or nothing,” and “Paradiso is the future,” on their car windows, almost blocked the view to the multi-story parking lot entrance. Meanwhile, parents and students made their way to the fourth floor, where the location consultation hearing for the Paradiso College Preparatory Charter School was held.

The school is in a historic building in Río Piedras, a San Juan suburb, where construction of a third floor began without construction permits. Operations in the structure were paralyzed after classes had begun because the location consultation process to get its use permit was incomplete.

Children in charter school uniforms, along with their parents, filled the entire fourth-floor reception area. In the hearing room, there was only space for about 30 to 40 people, leaving many of those in the reception and hallways who tried, in vain, to get in to listen or testify about the location of the school.

The proponent, Paradiso College Preparatory Real Estate II, through its lawyers Daniel Martínez Avilés and Gabriela Cruz, together with engineers Camilo Almeida and Eduardo Oliver Polanco, testified for one hour and 45 minutes to request that the educational institution be granted the use permit. The permit may be granted if the classification is changed from a tourist commercial zone to an intermediate commercial zone. Also, if they are granted an administrative permit that includes certain specifications determined by the city council, what Mr. Martínez described as “a tailored shirt” for Paradiso College.

The proponent’s table, filled with thick folders full of documents, barely left any room for Paradiso College Preparatory CEO Robert Acosta, his investment partner and Act 60 beneficiary, Brenton Nevárez; and the president of the entity, David Frontera.

Photo by Tatiana Díaz Ramos | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The testimony fell mainly on Almeida and Martínez, with a brief intervention by Acosta to explain the arrival and departure of students during operating hours. Dressed in a beige jacket and sky-blue shirt, Almeida spoke calmly in a historical account of the development of the urban area of Río Piedras. In the room, asleep children could be seen reclining on the shoulders of their grandmothers and mothers, while Frontera seemed to struggle to keep his eyes open sitting next to Acosta’s executive assistant, Doralba Rivera. Although he provided a wealth of historical data, the deponent could not tell Mr. José Fullana Hernández, who chaired the public hearing, the date when the structure located at 1000 Ponce de León Avenue was in use for the last time.

Almeida listed the different agencies that approved the educational project: the Fire Department, the Department of Health, the Puerto Rico Aqueducts and Sewer Authority (AAA, in Spanish), LUMA Energy, the Puerto Rico Tourism Company, and the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. He never mentioned the Department of Education (DE) or the Department of Transportation and Public Works (DTOP, in Spanish).

And it’s because the Department of Education only issued an educational entity certification in favor of the Paradiso Charter School.

“The Department of Education postponed the granting of the charter with the Corporación para el Desarrollo de Escuelas Alianzas de Puerto Rico, LLC, in the case of the two schools it will manage and operate,” the acting secretary of the Alianza Schools Office, Sol I. Ortiz Bruno, stated in written statements. “Certain documentation is required from the entity to disburse public funds that have not been provided,” she added.

The regulations for alliance schools establishes that, “In the event that a charter has not been granted between the certified educational entity and the Department, for reasons beyond the control of both parties, a memorandum of understanding may be granted to establish the temporary obligations and duties of the parties, which will be in force until the charter is granted.” So far, Paradiso’s headquarters in Arecibo continues to operate even though it does not have a memorandum of understanding or a charter signed between the agency and the proponent.

Students enrolled in Río Piedras are transported daily by school buses to Arecibo to study while the permits from the metropolitan headquarters are settled. On this issue, Ortiz Bruno said, “The Department of Education has not authorized the transfer of any student. However, parents have the final say on the decision about where their children go to school if the admission requirements and the appropriate space are met.”

Maril Cohen Frías is the mother of a student enrolled at Paradiso de Río Piedras and said the first day her son was driven to Arecibo, he vomited on the way there. After that experience, “I told him I was going to pull him out [of the school], but he begged me on his knees not to take him out of Paradiso.” And another mother, who identified herself as Yennifer Ortiz, said her daughter gets psychological therapy since she had to start commuting to the other charter school.

Meanwhile, Carmen Vázquez was disappointed that Río Piedras students, like her granddaughter, have to make such a long trip and come back tired at almost 6 p.m. to do homework and get up very early the next day to get there before the bell rings in Arecibo. However, she closed her presentation confident that the permit issue will be resolved because, “in the name of the Lord, through communication, everything is possible.”

In the two days that Paradiso College Preparatory operated in Río Piedras, traffic increased, the availability of parking on public roads dropped, and the constant honking insistently filtered through the windows of the neighboring building where Rodolfo Vázquez resides. The retiree was one of the 18 people, who after almost two hours of the presentation by the Paradiso representatives, had three minutes to express themselves in favor or against granting the use permit for the alliance school.

Paradiso asked the DTOP for new signage to identify the Ponce de León building as a school, however, the agency responded that, first, the institution must comply with a list of documents and requirements that must be submitted on or before the one-year term from when the notice was given. Otherwise, “we don’t recommend the proposed project, as presented.”

For her part, the president of the Fideicomiso para el Desarrollo de Río Piedras, Andrea Bauzá, asked that the proponent present a structural study of the building since they raised a third floor on a long-standing structure without presenting evidence that it could support another level. She also requested that they present evidence of compliance with access for people with disabilities, in accordance with the U.S. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Manuel Amador, a Río Piedras business owner, and member of the Community Board, questioned the need to open another school in the area when in 2017, the DE closed the José Celso Barbosa Middle School and the Luis Pereira Elementary School due to low enrollment. But, for Karen Mills, mother of a student at the alliance school, the Community Board’s opposition is invalid. “I am Paradiso, and if Ms. Jackie [García, chairwoman of the Community Board] doesn’t like it, it’s not our problem,” she said.

Three students, wearing a white polo shirt with the school logo and a green and navy blue plaid skirt, had the opportunity to express their desire to continue studying at Paradiso College Preparatory because “I didn’t get the help I deserved before,” “here I ask the teachers three times and they always answer me,” and because at Paradiso they have never experienced bullying, the students said about their six-week school experience. Meanwhile, the health teacher hired at the charter school and who the DE declared a surplus teacher, Edgardo Sanjurjo, wants to stay at the institution because “I’m heard here, I’m respected. I feel like I’m in Disney.”

Fullana closed the hearing by asking the proponent to deliver a list of those adjacent to the structure, certified by the Municipal Revenues Collection Center (CRIM, in Spanish), as well as a detailed plan with the signage of the places to drop off and pick up students in 10 days. He also urged other speakers to send their comments in writing in the same period. After receiving all the documentation, the attorney will write a report to the director of the municipal Permits Office, Víctor Joglar, to present his recommendation on the use of the building.

You may read some of the testimonies submitted for the location consultation by clicking on the links below: