Irene Espinoza, 85, has been bedridden for five years. She, like most older adults in Puerto Rico, has been particularly affected by the prolonged episodes of extreme heat that the island has been experiencing for more than five months.

Her skin, so fragile and thin, that it is lacerated even by the touch of a bed sheet, worsened during the summer, said her caregiver Luz Hernández from the driveway of her home in the Voladoras neighborhood of Moca, on the West Coast.

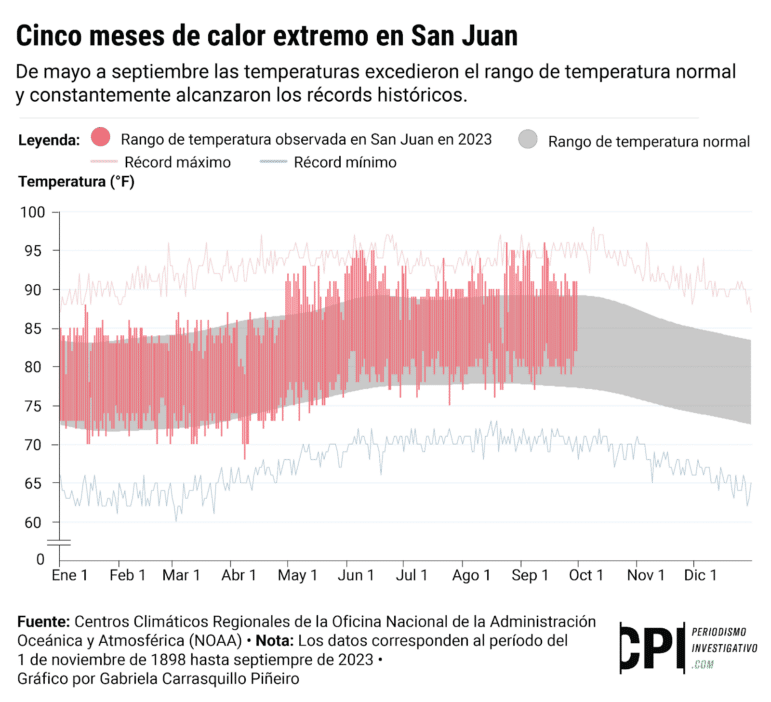

This year, the Island has experienced heat indices above 115 degrees Fahrenheit, and September closed as the hottest since 1899, the oldest date with record temperatures in Puerto Rico, according to an analysis by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) with data from the National Weather Service (NWS). This coincides with the extreme heat recorded worldwide in September, which has been listed by the World Meteorological Organization as the hottest month since the period between 1850-1900. This year, 2023, is also shaping up to be the hottest in history.

The CPI’s analysis also revealed an increase of up to 5.6º F in the average temperature on the Island in just one decade, between June 2013 and June 2023.

While this is happening, when asked if there had been deaths linked to 2023’s episodes of extreme heat, Health Secretary Carlos Mellado López said there is a case from 2017 in the Demographic Registry’s official database, which the CPI had already identified and does not correspond to the current situation. He did not answer a question about whether the agency was aware of people whose health has been affected by the extreme heat of the past few months.

Bedridden people and older adults are some of the populations most affected by extreme heat on an island that is aging, with 750,000 people over 65 years. However, the scale of those affected and how many deaths due to this may have happened during this year is unknown because it is difficult for doctors to know with certainty if the symptoms a patient presents are heat-related. Other affected populations are homeless people, pregnant women, and children.

Photo by Jeniffer Wiscovitch Padilla | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

“When you have heat indices of 120, 110, 113 [degrees Fahrenheit], and a population with a high prevalence of morbid obesity, a demographic pyramid in which Puerto Rico is aging, we have a high prevalence of cardiovascular conditions, cancer, hypertension, and diabetes. That’s what makes us more vulnerable to these episodes of extreme heat. We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people in Puerto Rico,” said Dr. Pablo Méndez Lázaro, associate professor of the Department of Environmental Health at the University of Puerto Rico’s Medical Sciences Campus Graduate School of Public Health.

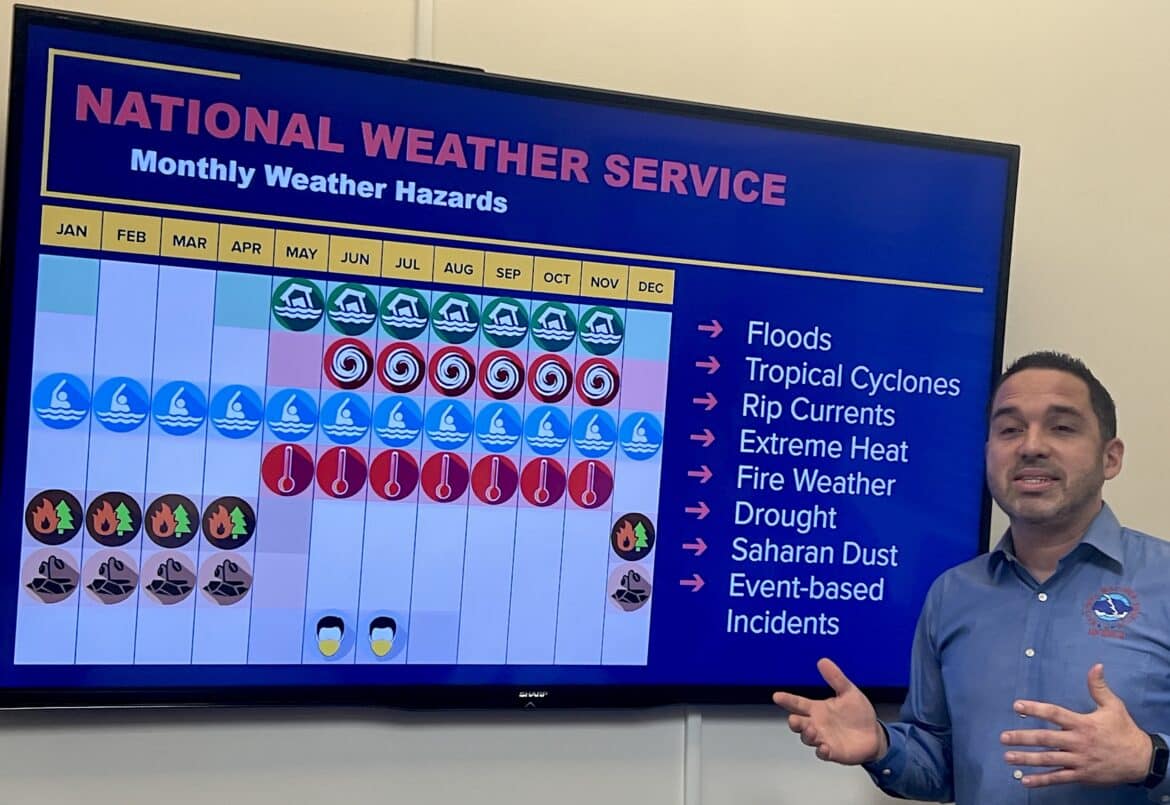

The heat index is a combination of humidity and temperature. It is also known as “apparent temperature” because it is how humans feel it, as Ernesto Rodríguez, director of the National Weather Service, explained to the CPI.

Méndez Lázaro said social factors, such as income and poverty level, are also added to this panorama of “heat-sensitive” conditions. As he explained, people who live below the poverty line and who have low acquisitive power, “will not necessarily have the money to buy an air conditioner or have it on for the entire time the heat episode lasts.”

This is Espinoza’s case, who during the summer did not have air conditioning. Today, thanks to a donation from a neighbor, she has the equipment that has helped her delicate skin.

It’s not just heat stroke

Dr. Méndez Lázaro, also a member of the Puerto Rico Committee of Experts and Advisors on Climate Change, said we must break with the view that extreme heat only causes heat stroke, but that there are countless other things that are altered and exacerbated in the human body with high temperatures. For example, people who suffer from hormonal changes who have hot flashes, and those getting chemotherapy, are affected by high temperatures.

“How many people in Puerto Rico are undergoing chemotherapy treatment under these episodes of extreme heat, and how many of them are below the poverty line? You have to be realistic; those are the ones who are suffering,” he said.

He mentioned that in the workplace, construction workers, airport workers, maritime and fishing industry workers, people who work on road construction, and farmers are most exposed to extreme heat.

“It’s not young people, it’s not healthy people, it’s not people with high purchasing power [who are most affected], it’s particular population groups and that must be addressed. “Not everyone dies from the heat, of course not, just like not everyone dies from floods,” he said.

“There are other things that exacerbate heat, like heat islands. So that also makes the place where you live, your home, more vulnerable or more exposed to extreme conditions. “Densely occupied areas are more likely to retain extreme heat than those areas that have gardens, parks and green areas,” he added when explaining the concept of heat islands.

In 2016, Méndez Lázaro worked on research that analyzed the impact of high temperatures on mortality during the period from 2009 to 2013. It found that the risk of death of people with cerebrovascular and cardiac conditions in San Juan and Bayamón, near San Juan, increased during the summers of 2012 and 2013. These conditions were intensified by the heat, he explained.

The professor is currently working on a more comprehensive study, which analyzes mortality and extreme heat from 2015 to 2020 in the Puerto Rico archipelago. There are no other recent studies on the topic.

The CPI analyzed Puerto Rico’s mortality data from 2015 to May 2023, which only reported one official death due to “heat stroke” since 2015. This was a construction worker who died in 2017. However, this data excludes most of the heat wave period that began this year in April 2023 and is ongoing, because the Department of Health did not provide the most up-to-date data. This organization sued the agency and Secretary Mellado López for the delivery of incomplete data for the most recent request submitted for another journalistic investigation.

However, the experts interviewed agree that Puerto Rico’s mortality data does not reflect the real impact of extreme heat on the health and mortality of the population for several reasons. Among these, heat stroke is difficult to diagnose, and heat worsens pre-existing chronic conditions that end up being the official cause of death. Furthermore, they maintained that, as happened with the deaths linked to Hurricane María, doctors and morticians have not been trained to identify and record on death certificates the links between heat and mortality.

Internal Medicine Doctor Hiram Rodríguez, explained that high temperatures can affect all the organs of the body, including the kidneys and the heart. However, as he said, heat stroke is “the most severe manifestation of these disorders of high temperatures in the environment that affect the body.”

He said that for there to be a heat stroke diagnosis, the patient must have a temperature of 105ºF, have been exposed to extreme heat, and it must be ruled out that this temperature is not the result of other diseases or medications that the patient is taking.

Rodríguez said that given the heat events that have been recorded in Puerto Rico, doctors should “suspect” the possibility that a patient is experiencing heat stroke, especially when the heat index is above 100ºF and who presents symptoms such as high temperature and confusion.

He explained that people with symptoms of heat stroke usually arrive at emergency rooms.

For his part, emergency room physician Fernando Soto, who directs the emergency room at the San Lucas Episcopal Medical Center in Ponce, in the South, told the CPI that the training that specialists like him receive enables them to address temperature-related emergencies. However, he said, “the majority of doctor-patient interactions that take place in emergency rooms in Puerto Rico are between generalists and patients, and not with emergency room specialized physicians.”

The former president of the College of Puerto Rico Emergency Doctors said these health professionals are the “minority” in emergency rooms and that there are currently only approximately 200 on the Island. Puerto Rico’s population is 3.2 million people.

Soto said in the last 10 years, he has attended very few heat-related emergencies. They have been from bedridden people and tourists who were exercising and unfamiliar with the Island’s climate.

However, Dr. Soto agreed that it is not easy to make this type of diagnosis because it can be mistaken for other diseases.

“I think that one of the limitations that Puerto Rico has in terms of death certification is the little documentation they have or the follow-up that many of the patients have with their primary doctor in many centers. In other words, it isn’t very clear what people are suffering from when they arrive at the emergency room, there’s no communication with these specialist doctors, sometimes, and it’s a little tough due to this limited information to reach the conclusion that it is one diagnosis and not another,” he explained.

“If you arrive [to the emergency room] with a high fever, dehydration, kidney failure, well, the most common cause of high fever and kidney failure is sepsis, it’s an infection,” he said, explaining that it can be difficult for a doctor to make the connection with heat.

He said, for example, one of the three most common causes of death in older adults is sepsis, which manifests itself in dehydration, organ failure, and fever.

Soto assured that heat does increase mortality, but not only due to heat stroke as a diagnosis, but also due to other previous causes that the person suffered from, which are exacerbated, such as, for example, patients with heart failure, heart attacks, and kidney failure, among others. He said the heat stroke diagnosis entails a complex picture of symptoms, which includes dysregulated [hypertensive] temperatures, organ damage, and mental changes, such as disorientation, among others.

He explained that people with previous conditions could die from a heart attack or kidney failure, among other causes, before presenting the symptoms of heat stroke.

Soto assured that the population most at risk is the elderly. He explained that the body’s signal that lets people know that they are thirsty and should drink water is less effective in older adults, adding to the fact that some patients take diuretic medications. Others cannot get up to get a glass of water because they are bedridden. In some cases, older adults with disabilities or illnesses such as Alzheimer’s or dementia cannot ask for water. “So, if you want to draft public policy that protects the population most vulnerable to heat events, senior care centers should be number one,” he said.

More than 85% of older adults in Puerto Rico live in their own homes or with relatives, not in care centers.

Much to do for the aging population

According to Carmen Delia Sánchez, Puerto Rico Advocate for the Elderly, not all nursing homes and elderly care institutions have air conditioning, and it is not a legal requirement they have it. What is required is to have cisterns and power generators.

She added that from a social perspective, it is known that very few older adults have air conditioning at home or can use it for a long time due to economic reasons. In Sánchez’s opinion, this is the demographic group most affected by the heat.

According to data from the Health Department’s Syndromic Surveillance System, which is a combination of indicators that the agency uses to monitor diseases or public health situations, there have been 183 “alerts” of diseases related to heat or lack of electricity from January to September of this year. The week there was the most was June 3-10, with 15 alerts. This system uses data collected in medical records from visits to emergency rooms or emergency visits to health service provider facilities such as hospitals or Diagnostic and Treatment Centers (CDT, in Spanish).

The report explains that alerts should be interpreted as trends in the disease or health event of interest.

These data are reported to the Health Department through the ESSENCE digital platform, (“Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics”), which is the syndromic surveillance system’s main tool.

According to the data from the last report, issued October 2, only 18 hospitals were periodically sending syndromic information to the Health Department, which represents 9.63% of the emergency rooms in Puerto Rico.

The impact on workers

In addition to the elderly population, Dr. Soto assured that workers who are under the sun are the most impacted by the extreme heat.

Such is the case of Omar Vázquez, Félix Soto, and Israel Santiago, who work from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. as gardeners in a hotel in Guánica.

Photo by Ricardo Rodríguez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

For Vázquez, it is “tedious” to work under high temperatures. He said his employer provides them with 15 minutes of rest in the morning and 15 in the afternoon, apart from lunchtime, and if they feel suffocated, they can also take more time or look for shade to mitigate the heat.

“June and July have been tough, and we’re approaching Christmas, and the change has not been seen yet,” said the gardener interviewed in mid October.

Alessandro Cordero, who also works at the hotel’s pool and beach areas, said he has felt fatigued by the heat, so he has taken measures to protect his health, such as staying hydrated.

Changes are urgently needed to face extreme heat

“We’re living at a time when we must adapt and modify our lifestyle to be able to survive these changes. For example, right now, construction work is done during the day, the roads, the work on houses, roofs… A law or municipal ordinance must be passed. Let’s try to do these jobs at night, when the weather is cooler, because we’re exposing lives,” said Ernesto Morales, National Weather Service meteorologist, about the need to change laws and ordinances to adapt to these changes.

Meanwhile, Ernesto Rodríguez, director of the National Weather Service, said each individual and municipal administration must self-evaluate their vulnerability to weather conditions or climate. He explained that, for example, people who live in the mountains are more vulnerable to landslides than heat. So, he said emergency plans must be focused on each municipality’s risks.

Photo by Vanessa Colón Almenas | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

“If each municipality does that, and the plans are based on the main risks of weather and climate factors, with the limited resources we have, we will be better prepared,” Rodríguez said.

He said they plan to hold a conference next year on specific actions that can be taken to begin the adaptation process. “Climate change is already here, it’s upon us, it’s happening, we can talk about it and the causes, but we have to take action now.”

In late September, the Committee of Experts and Advisors on Climate Change presented a draft of the “Mitigation, Adaptation and Resilience Plan on Climate Change in Puerto Rico.” This document will go to public hearings in the legislature next year.

The plan addresses the issue of heat and presents strategies, such as the development of a surveillance and monitoring system for the effect of extreme climate events on public health, considering extreme heat, hurricanes, dust from the Sahara desert, droughts, and floods. Another proposal is to establish measures to protect the vulnerable population from extreme temperatures and heat waves.

Meanwhile, Dr. Héctor Jiménez, director of the Climatology Office of the University of Puerto Rico’s Mayagüez Campus, said every time a building cools down from the inside, the outside gets hotter, not only because of the heat that was expelled, but because of the electrical energy that was used with the air conditioning, which generates a heat island. So, he said, solutions must be sought to build structures that do not depend so much on artificial cooling: the urban area must be massively reforested, one of the most accessible things to do, and that can have a very significant impact.

“A large tree with a large treetop not only provides shade, that’s one of the benefits; people don’t talk enough about the fact that a large tree also has a cooling effect. It works as if you had an air conditioner,” said Jiménez, who added that this is equivalent to a 36,000 to 69,000 BTU/hr air conditioner (depending on the size of the tree), and that there are already countries like Singapore that are planting trees to deal with the problem.

On the other hand, he acknowledged that presently, the Climatology Office has not studied the effects of heat on the most vulnerable. He said it’s hard to do this type of study because it’s not easy to get medical records or statistics of the people who come looking for medical services.

“It’s not clear that when someone comes to seek medical services because they feel dizzy [it’s because of the heat]. There are times when it’s obvious that they were working in the yard and overheated,” he said. He added that in other cases, there are people who feel bad being inside the house, and it can be attributed to some previous condition they have. “But it’s very possible that the reason why [the condition] worsened was because they were experiencing extreme heat. And that isn’t so easy to quantify,” said Jiménez.

“Unless we become a little more aware of this and health care providers start making these notes and saying, well, ‘at least there is a suspicion that this was caused by a heat event,’ it’s not going to be very easy to make that connection in Puerto Rico,” he said.

The Climatology Office is generating historical data on heat indices, which will allow them to compare with current data, he said. His office, whose duties include taking a historical look at past trends, does have temperature data from 1898 to the present but has not worked with the indices. Although data began to be collected that year following the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico in July 1898, the first year with complete data was the following year, 1899.

Jiménez explained that the more humid the environment is, the harder it is for the body to evaporate sweat and for the body to cool down.

“It becomes harder for us to regulate body temperature, because body temperature must be within certain ranges, and the higher the index is, the harder it is for us to maintain those temperatures. There may come a time when you cannot maintain the temperature, and then the health risks begin, and the first to be at risk are the people who are compromised in some way, the most vulnerable,” said Dr. Jiménez.

He said the heat index has its limitations, such as, for example, it does not consider solar radiation. In other words, a worker who is on the street, under the sun, with a high heat index, is at greater risk.

Government agencies notice the change in the workplace

According to the local Department of Labor, the OSHA (U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration) office in Puerto Rico adopted the National Emphasis Program (NEP) last year, which aims to identify, reduce, or eliminate occupational exposures to heat in several industries.

That began to codify inspections related to these risks in the summer of 2022.

From April 2022 to the present, it has carried out 76 formal inspections where occupational risks due to heat exposure have been addressed. Thirty of these inspections were motivated by employee complaints, and 46 inspections were scheduled for high-risk heat industries, according to Judith Cruz, assistant secretary of the office.

None of the inspections carried out had citations or complaints related to heat, she assured. One of the cases was initially investigated as a possibly heat-related fatality, but the case was closed without citations or accusations since the autopsy results revealed that the cause of death was natural due to pre-existing conditions of the employee, she added.

However, she said OSHA does not have specific regulations for occupational heat hazards.

The Puerto Rico Labor Department assured that it has taken measures to guide employers and workers about the effects of high temperatures at work and avoid risky situations and fatalities.

On the other hand, according to data from the Puerto Rico State Insurance Fund, the cases they have treated and have received the diagnosis of “hyperthermic shock (heatstroke, sunstroke)” have been increasing in the past 11 years. From 2012 to 2022, 53 cases have been registered, this last year having the highest number, with 10 cases.

Why the extreme heat?

National Weather Service Hydrologist Odalys Martínez said although the record of the summer of 2012, when there were 36 consecutive days with temperatures above 90ºF, has not been surpassed, this year has been worse because the temperatures at night do not drop. As she explained, at that time of day, temperatures cooled down, which is not happening now.

Ernesto Morales added that this also has to do with the heat wave in the Atlantic Ocean. He said ocean temperatures around Puerto Rico are currently around 87º, making it harder for temperatures to cool off.

Martínez said that although temperatures are expected to continue rising, it is unknown if, for example, next summer will be just as hot.

Extreme heat has affected Puerto Ricans since May, and even in October, heat indices above 100 degrees continue to be reported.

Próximo en la serie

2 / 2

Calor histórico afecta a los más vulnerables en Puerto Rico

17 octubre 2023

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.