It’s 11:00 a.m. and Manuel Román, whose body and face are wrapped in t-shirts to protect himself from the sun, ends his fishing day that began at 6:00 a.m. in the Guánica Bay, on Puerto Rico’s southern coast.

The stench emanating from the bay is unbearable on this side of the coast, and although there are several factors that have contributed to its pollution, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been investigating since 2018 the presence of a chemical that has been identified in these waters at levels that represent a health risk to the community and the environment. They are polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a substance that is commonly used as a lubricant in electrical transformers and that the EPA banned in 1979.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Although the EPA knew since 2020 that the contaminated area of the bay was used by residents for shellfish consumption, the EPA’s Caribbean Division, which is handling the case, denied to the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) for seven months that this activity was actually taking place . But in statements days before the publication of this investigation, the EPA accepted that it erred in assuming that fish from the bay were not being consumed.

“We recognize the confusion about the consumption of fish from Guánica Bay by recreational fishermen. Previous references the EPA made, which suggest that the community did not consume fish from the bay, may have originated from anecdotes offered by local sources,” the agency said in response to questions from CPI. “EPA advises the public to use caution when considering consumption of fish and crabs from Guánica Bay. We’re actively working to address these concerns and ensure the safety and well-being of local communities,” they added in writing without detailing what specific measures they are taking.

Screenshot of the EPA file on the case.

The local and federal governments have not yet alerted the public or prohibited fishing in the area that is visited by fishermen and visitors from different parts of the archipelago. The EPA says that the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA, in Spanish) and the Department of Health are the agencies that could intervene preventively, while the DRNA says it has not acted because the EPA is the one that has control of the entire process.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the EPA itself, it has been established that prolonged exposure to high concentrations of PCBs could cause some conditions — including cancer — of the skin and liver, impact the immune system, affect cognitive development in children and during pregnancy. They state that more studies are still needed on the effects of PCBs on human health.

The Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board reported the chemical with carcinogenic potential in Guánica in 1998, on the land where one of the Ochoa Fertilizer factories operated. It took the local and federal governments 20 years to investigate the case and alert the communities.

In 2018, the EPA confirmed the presence of the chemical substance in 43% of the backyards of homes and businesses included in its sample in the Esperanza neighborhood, and in 2022 the area was included in the list of national priorities of its land cleanup program known as the Superfund. In March of this year, W.R. Grace, owner of the land, reached an agreement to pay $10 million for the cleanup. The work has not yet begun, according to neighbors interviewed. When asked by the CPI, the agency confirmed it would begin in early January. While the cleanup is being carried out, classified as an emergency by the EPA, the investigation that would extend to the bay is on pause.

The EPA maintained that, although the findings of other scientific investigations about the contaminant in this body of water were the reasons for going into the area to investigate, they cannot take any preventive action until their own investigation is completed.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), affiliated with the U.S. Department of Health does have an ongoing investigation into existing public health risks that includes the water in the area, but does not have an estimated completion date.

The director of the EPA’s Caribbean division, Carmen Guerrero, said her agency cannot take preventive measures in the bay unless ATSDR recommends it.

“If we knew that there was any imminent risk or danger to the community, those preventative measures would be taking place.

It’s not necessary for them to be included in a document for me to say: ‘EPA, you have to stop this and avoid this exposure,’” said the toxicologist who leads the federal Health investigation, Luis Rivera González.

Meanwhile, life goes on there for those who live off what they catch.

Uncertain impact on residents’ health

Manuel has been supporting his family with fishing for 25 years: grouper, sardines, Mahi Mahi, snapper. He learned to fish from his father, who has not been able to go back to the sea since he started chemotherapy for liver cancer, a disease also suffered by three of Manuel’s uncles who died last year, the fisherman said.

“We have always said: ‘It’s this rottenness, [that] has killed us little by little.’ […] You become afraid of this here, but we, who were born and raised here, sometimes say ‘nah’, forget about it,’” he says while smiling resignedly.

Photo by Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The stories of sick people are repeated in the communities that border Guánica Bay: liver diseases, colon cancer, kidneys, but given that the government of Puerto Rico has never investigated the impact of the contamination of this area, which has been one of high industrial activity for decades, the number of people who may have died from this cause is unknown.

Four experts in public health and environmental sciences that the CPI consulted, noted the cumulative characteristic of the chemical in the body, particularly in cases in which people have been exposed for a long time.

“Once you consume PCBs through food, air or water, they don’t leave your body, they’re fat-soluble, which means that they adhere to the fat in your body and continue to bioaccumulate,” said scientist Naresh Kumar, from the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Miami.

“They start at the low end of the food chain, like [what happens with] mercury, and it bioaccumulates until it reaches a point where if it gets into your body there’s no way to get it out, because it likes to be there. So, PCBs are a problem,” said Ingrid Padilla, professor at the Mayagüez Campus of the University of Puerto Rico, specialist in contamination of water resources.

Local government participation is imperative in the face of potential risks

Four experts also noted that, while the EPA concludes its investigations, the municipality and local agencies could take coordinated measures with the federal agency to alert the population and minimize the risk exposure of the communities in the area. This may include, at a minimum, warnings in the affected area and educational efforts that make information accessible to the community and visiting public.

“This cannot be a secret […] If the local government already knows what’s happening in that bay, it’s also appropriate to have risk communication and education plans so that there’s a reduction in exposure, minimizing exposure to these contaminants while [the EPA] is doing the cleanup,” said Pablo Méndez, professor of Public Health at the University of Puerto Rico’s Medical Sciences Campus (RCM, in Spanish).

The multiple sources of pollution to which the communities in Guánica have been exposed, and that have contributed to the current state of deterioration, result from the negligent industrial activities in the area such as the inadequate management of contaminants that ended up in soils and bodies of water, the experts agreed.

“It shows an industrial management practice that wasn’t the most appropriate. You must think that it was the 50s or 60s, and most of the environmental regulations that we currently have in force did not exist,” said Luis Bonilla, professor of Public Health at the University of Puerto Rico’s Medical Sciences Campus.

Meanwhile, Méndez said “the buildup of bad practices that the private sector has had in the region and the little information that the community has also had about the risks to which it may have been exposed shows there may be greater type of exposure to these contaminants.”

Although local authorities have known about the potential exposure to the contaminant for almost three decades, the CPI found that only one effort has been made to inform the community on how to avoid exposure to PCBs in the area. The initiative was a collaboration between scientist Kumar’s team and the Áurea E. Quiles Claudio High School to educate the community about the contaminant, its presence in the bay and safe ways to consume fish if necessary.

During Kumar’s investigation, more than 300 Guánica residents were interviewed between 2014 and 2018, before and after the educational campaign. They found that consumption of seafood caught directly from the bay decreased from 57% to 41%.

“We were quite serious about telling people to try to eat as little fish as possible from the bay, but if they were going to eat it, do it safely: just eat the filet without much of the fat, removing the skin, removing the head,” said Michael Gambale, who participated in the campaign as a high school student.

From the Legislature, pro-independence Senator María de Lourdes Santiago Negrón presented a resolution that orders the School of Public Health of the UPR Medical Sciences Campus and the Department of Health to conduct an epidemiological study to investigate whether there is a causal relationship between exposure to high levels of PCBs, several heavy metals, and other contaminants identified in the area. It also orders an investigation into “the health conditions suffered by the residents of Guánica, with emphasis on the communities surrounding route PR-333, the mid- and long-term effects and the impact of such exposure on the community’s health.” The measure was presented and referred to the Senate Health Commission in June of this year. However, it was not addressed, the senator’s environmental advisor confirmed.

The action responded to a request from Guánica residents following the EPA’s intervention in 2018 and the little information they have received about the extent of the contamination and the possible risks they face.

Scientifically relating exposure to a contaminant to the development of certain health conditions in a community is very challenging. Senior scientist and principal investigator at Northeastern University in Boston, Gredia Huerta Montañez, said contrary to the control that can be had in clinical trials, in the field of environmental health it is often difficult to estimate the effects caused by a pollutant and differentiate them from the chance of developing a condition, since there are many toxins and contaminants to which a population can be exposed throughout its life.

“When we’re seeing a mixture of chemicals, it becomes even harder,” she warned about the complex pollution panorama like the one that exists in the bay.

Active fishing activity in the bay due to the EPA’s and the Municipality’s denial

Although the EPA and the Municipality of Guánica claim that those who practice recreational fishing in the bay do not consume what they catch, data from the DRNA show the opposite. From July 2020 to July 2023, 114 people who practiced recreational fishing in Guánica Bay were interviewed. The data was provided by DRNA biologists who work for the nearby Guánica Dry Forest and analyzed by the CPI, and it appears that 56% of the people who were successful in their fishing took the fish home. Of the total number of people interviewed, 75% are from Guánica and neighboring Yauco.

The data shared with the CPI on shore fishing is collected as part of a Guánica Dry Forest project. The research methodology, which is still ongoing, uses a survey as a tool, carried out at random times and days.

Although the EPA has not yet investigated the bay, several entities and researchers have done so since the 1990s, including the EQB, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Miami.

In the process, in 2014 Guánica Bay was discovered to have the second highest concentration of PCBs in the world, contaminated fish and eventually high levels of the compound were confirmed in the bodies of Guánica residents. After the hurricanes in 2017, it was also found that the environmental concentration of the pollutant had increased fourfold in the bay.

The Municipality of Guánica’s Administrator, Omar Pacheco, said the only measure taken in the bay by the DRNA to protect people’s health was the cancellation of the Guánica Bay crossing swim event in the eighties after declaring the waters not suitable for bathers. He said that at that time signs were installed warning about the contamination of the water.

But after multiple visits to the bay, the CPI was able to confirm that there is nothing that warns about the health risk of consuming what is caught or swimming there. Area residents have not seen warning signs in recent years. There is barely a sign on the boardwalk, which is not where most fishermen go, and which states in general terms and fine print that fishing and swimming in the area are prohibited,but no reason for such warning is given. The sign is illegible because it is hidden behind another sign and has extremely small lettering.

Courtesy photo.

“[Shore fishing] stopped because of the same situation of the apparent contamination of the bay, which we most likely know is contaminated,” said the municipal official, adding that they are waiting on what course to follow based on what scientific investigations have found in the area.

In response to the findings on the activity and consumption of fish caught in the bay that the CPI showed him, the Administrator said he will contact the DRNA to see how the Municipality can cooperate in providing guidance to fishermen and the public.

EPA, DRNA blame each other for the lack of diligence in Guánica

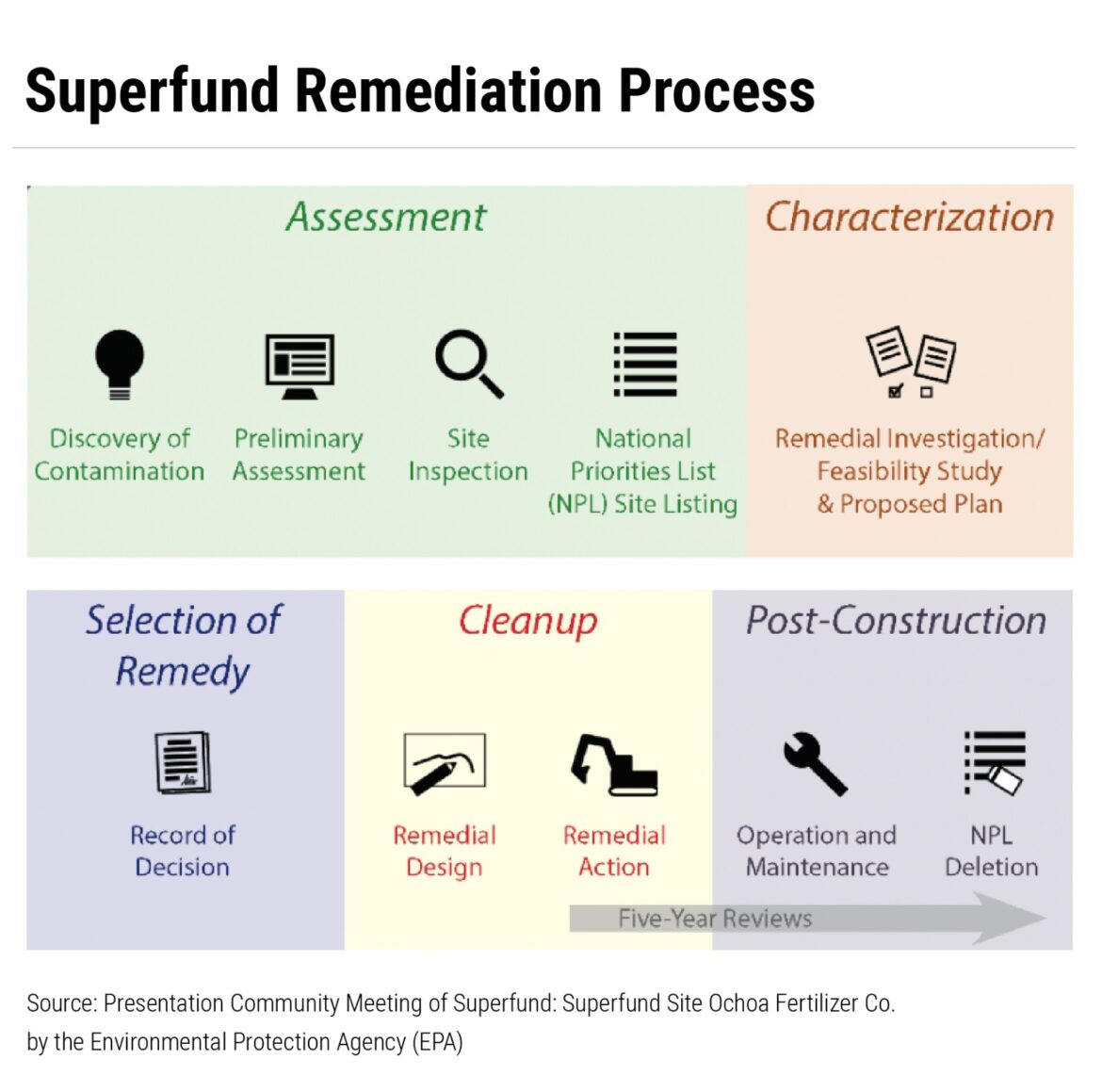

The agency in charge of identifying the responsible parties and ensuring that the cleanup of the contaminant in the bay and the affected lands in Guánica is done is the EPA — The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) guides the Superfund process and does not establish specific time frames for addressing a case.

Guerrero and project manager David Cuevas blame the bureaucracy and high volume of cases for the agency’s extreme delay in addressing the matter, conducting the studies, and taking the necessary corrective actions to deal with the contamination in Guánica.

However, Guerrero said in an interview with the CPI that, while the EPA waits for US Department of Health recommendations, the DRNA and the Puerto Rico Department of Health can take preventive measures to avoid fishing in the bay.

Photo provided by the Municipality of Guánica

The CPI asked the local Department of Health for information on its participation, if any, in cleaning the area, but there was no response.

The only DRNA division that claims to be aware of the situation is its Superfund Division because it has been contacted by the EPA as part of the program’s formal process. However, the manager of the area to which this division belongs, Edwin Malavet, said that they are not responsible for measures that are needed in the bay to alert the public. The project manager of this division, Pascual Velázquez, who participated in the original EQB investigation in the 1990s, said he does not remember the details of the investigation in which he participated since it took the EPA 18 years to contact them again. He said his agency, in addition to recommending several actions to the EPA, took no further action on the 1998 findings because that federal agency is the one “in charge of everything.”

The director of the Guánica Dry Forest, Darien López Ocasio, regretted that the EPA does not consider the experiences of the communities and her work team. She acknowledged that the bureaucracy in the DRNA has hindered the process from its central offices, but she said she was willing to contribute by installing notices to mitigate any risk to citizens.

The biologist told CPI that she learned the details of the cleanup process during a meeting between the local scientific community and the municipal government, and not directly from the EPA. The remediation project manager of the EPA division in the Caribbean, geologist David Cuevas, was invited there to provide details of his intervention at the site and receive comments.

“I was concerned and raised a flag because it doesn’t appear from the [EPA] presentation that they are considering that recreational fishing and consumption of these fish was a problem. They thought that commercial fishermen were going out to sea, but there’s a population of recreational fishermen who are visiting,” she told the CPI.

She added that, unlike recreational fishing that happens in reservoirs, it’s more common on the coast for people to consume what they catch.

No answers from EPA on fish contamination

In 2015, a team from the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Miami, led by scientist Kumar, found high concentrations of PCBs in two fish in the bay as part of a study that sought to map the distribution of this contaminant in this body of water. A concentration of 1.6 ppm or parts per million was found in a snapper fish (Lutjanus analis). While in a mojarra fish (Eucinostomus gula) 3.7 ppm was found, which exceeds the levels recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the consumption of fish and shellfish (2 ppm).

Photo provided by the University of Miami

However, Guerrero told CPI that the EPA cannot rely on the work of other scientists to take preventive measures. “Right now, there’s no decision for a fishing warning . Additional studies are required for that,” she said.

Given the concern about the University of Miami’s findings on contaminated fish, the toxicologist who leads public health research in the area, Rivera González, told the community that until then, the findings of that study were not a problem because a too small sample was used. This happened during the first community meeting last March, which CPI covered.

Photo provided by the Municipality of Guánica

The EPA Superfund National Priority List includes the sites most affected by pollutants hazardous to human health and the environment in the United States and territories served by EPA.

Decades of waiting while the risk of contamination continues

After the 1990s findings, and in an unrelated effort, NOAA marine biologists in 2007 found PCBs in coral tissue and sediment along a nearly 14-mile coastline, with the bay being where they found the significantly highest concentration. This was the start of a pilot project that today is led by the Protectores de Cuencas organization and that took place without knowing about the EQB’s findings on Ochoa Fertilizer, a former subsidiary of W.R. Grace, owner of the land that is part of the Superfund.

The University of Miami continued NOAA’s work to identify possible exposure through consumption of potentially contaminated fish. The work took more than 10 years. The EPA was not part of this entire effort, so the decision to address the Guánica case in 2018 came about after the scientific community rediscovered the high levels of PCBs in the environment in Guánica, the CPI found.

10 times higher concentration in sampled residents

“It’s obvious that if PCBs are in the environment, in the sediment, obviously, they will be in shellfish, they will be in the air, water and, of course, people will be affected,” Kumar said in an interview with the CPI.

“The concentration of PCBs in the population of the municipality of Guánica is more than 10 times the concentration found in the population of the United States,” warned Kumar, who took 150 blood samples from Guánica residents and whose research is not yet available to the public.

Seeking that his work would lead to the EPA investigating the area and including it in its list of national Superfund priorities, the scientist remembers sharing his work with the municipal government and believes there was political concern about the impact it would have on tourism and other sources of income in this town. “They [EPA] were not very receptive to this idea” of the site being declared part of the Superfund, he said.

Despite the importance of Kumar’s project to protect the Guánica population’s health, the grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH) that financed his project ended, and the researcher has not been able to go back since 2020.

The scientist, who since 2014 has been investigating the impact of the contaminant on the community, said that more work is needed to understand the impact that the contaminant has had on residents who already have high levels of PCBs in their system.

Photo by Jorge Ramírez Portela | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

“Do they really have a high incidence of certain diseases? And if so, what is it? At least physically, those people who have high levels should be the target of intervention,” he concluded.

“Aunt Aidé, kidney, head and breast cancer; Aunt Mirian, a very rare cancer and it took her kidneys; Uncle Atino, liver; Uncle Rumboldito, on his skin; my mom, melanoma [a skin cancer]; and then we have the liver, we all have liver problems,” said Ada Vélez, a neighbor whose home faces the Guánica boardwalk.

“My nephew died a few years ago, a young guy, from kidney illness and cancer,” she added.

This is one of several testimonies that the CPI collected in the Pueblo and Ensenada neighborhoods about deaths and cases of different types of cancer. According to data from the Department of Health that the CPI analyzed, the Ensenada neighborhood, to the west of the bay, led the incidence of cancer mortality with an incidence of 75 deaths as the main cause compared to other neighborhoods — which did not exceed 44 deaths — in the period between 2015 and 2022. Ensenada has a population of 1,172, according to the 2021 U.S. Census. It is the second least populated neighborhood in Guánica. In contrast, the Superfund area under investigation by the EPA is on the opposite end of the bay, far from Ensenada.

Communities in limbo

After the consolidation of agencies in 2018, the EQB, from its Environmental Emergencies Area and DRNA Superfund, is still the one that collaborates with the EPA.

The CPI had to go to court after seven months of waiting for the DRNA to deliver the Ochoa Fertilizer Co. case file. The CPI found that the only action the DRNA took was in 2021 in support of the EPA to include the area on its Superfund National Priorities List through a letter signed by the then Secretary Rafael Machargo Maldonado.

Photo by Jorge Ramírez Portela | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

“We have no one to handle or pay attention to the condition of the island’s environmental quality. So, the situation in Guánica dramatizes that inability that the State has been building to [assume] that basic responsibility that is fundamental for any government in any democratic society that ensures the health, safety, and well-being of citizens,” Planner Félix Aponte warned .

He also expressed reservations about ATSDR’s work, particularly regarding the reliability of its previous public health investigations in other Superfund areas in Puerto Rico.

“We must be grateful that the EPA shed public light on this, but I believe we must delve much deeper into the situation of the Guánica pollution problem. La Caribe, La González, La Ochoa, with all the names they had, robbed Guánica of its heritage, because the most beautiful thing that Guánica has is the bay, and we have a bay that can be open to so many activities and it can’t be because it’s contaminated and no one talks about how we’re going to decontaminate it,” said Vélez, who lives in front of the boardwalk. “Pushing off the future of a bay that is constantly polluted doesn’t make sense,” he said.

This investigation is the result of a grant awarded by the CPI Journalism Training Institute and was possible in part thanks to the support of Para La Naturaleza.

Próximo en la serie

4 / 4

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.