MADRID — No Puerto Rico delegation took part in the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Madrid, but decisions made as the fractious two-week meeting came to a close on last Sunday could spell disaster for the territory if the United States and a handful of other large countries don’t change their ways, island nations said.

“The big polluters and the countries that emit the most are not wanting to take responsibility or leadership,” said Ramón Cruz, a Puerto Rican expert in climate change and international relations and vice president of the Sierra Club, adding, “We’re living the effects of the climate emergency and they’re not standing up to the problem.”

As a US territory, Puerto Rico — which was named the country that suffered the most from extreme events from 1999 to 2018 in the 2020 Global Climate Risk Index — is not allowed to send its own delegation to participate in the crucial annual negotiations.

“It’s very difficult for us to really play any part in it because we’re represented there technically by the US, and the US could not care less about Puerto Rico,” said Mr. Cruz.

Under President Donald Trump, he added, the US hindered progress at the talks even though it plans to withdraw next year from the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement, which commits nations around the world to work toward cutting carbon emissions enough to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“It was really unfortunate that the Trump administration was throwing so many wrenches in the process even though they don’t want to engage,” said Mr. Cruz. “They’re not living up to it and they’re not leaving anybody to pursue their commitments.”

However, he believes that Puerto Rico’s perspective was closely reflected by independent island nations that were very vocal at this year’s talks. Throughout the conference, the Alliance of Small Island States pushed hard for new commitments to reduce the carbon emissions that cause global warming and to increase financing for poorer countries that are on the front lines of the crisis. The result, however, fell far short of what is needed to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement’s goals, they said.

“As COP25 draws to a close and islands wade through and beyond the glitzy public relations and buzzwords, we are astounded,” the 44-member alliances announced Sunday afternoon in a statement. “We are appalled and dismayed at the failure to come to a decision on critical issues, the scale of inaction, ineffective processes, and some parties’ yeoman commitment to obstruction and regressive anti-science positions.”

A main goal of the conference was to finalize and adopt Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, setting rules for a carbon market designed in part to incentivize emission cuts by allowing countries to fund climate work abroad in exchange for credits back home. But as the final plenary came to a close a record 44 hours late, that decision was bumped to the COP26 next year in Scotland.

Mr. Cruz and other island representatives were very disappointed by this result, but he said a delay was better than adopting a bad deal.

Another goal of the conference was to review the 2013 Warsaw International Mechanism, the UN framework for addressing “loss and damage” suffered by countries as a result of climate change.

“For the islands, the whole issue of loss and damage was extremely important, and there’s some mixed outcomes — there was at least some language that was good — but ultimately there were some key aspects like the governance and ultimately how much money there’s going to be on the table that [is] not there,” Mr. Cruz explained.

AOSIS agreed that climate financing commitments were lacking.

“We welcome the near $90 million pledged to the Adaptation Fund at this meeting,” the alliance stated. “But adapting to [limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius] costs vastly more. Loss and damage is an existential issue for AOSIS member states. Several islands in the Pacific have already been inundated. Lives have been lost.”

AOSIS’s concerns were echoed by many other delegates, including the least developed country grouping.

“There is a vast disconnect between the urgency we are feeling at home and the pace of these negotiations,” LDC group chair Sonam Wangdi said after the conference.

And on Sunday, COP25 Chair Carolina Schmidt, Chile’s environment minister, conceded: “We are not satisfied. The agreements reached by the parties are not enough.”

Throughout much of the talks, island nations and other countries blamed a handful of large nations they said were reluctant to move forward with sufficiently meaningful action, including the US, Brazil, Australia and Saudi Arabia.

A major friction point among the large holdouts involved questions over who should pay for that action, according to AOSIS negotiator Carlos Fuller: A few wealthy nations were reluctant to increase financing, but poorer countries balked at cutting emissions without pledges that they deemed sufficient to help them shoulder the cost.

At times, he said, poorer countries seemed fixated on pointing fingers over their wealthier counterparts’ failure to meet past financing goals.

The Paris Agreement commits countries to provide $100 billion per year in climate financing by 2020. Because of debates over what kind of spending should count, the progress toward this goal is unclear, and many argue that it is far off.

The US’s reluctance to move forward caused particular rancor among some delegates because of the country’s plan to exit the Paris Agreement next year under Mr. Trump, who has denied that humans are causing climate change.

Mr. Cruz said this year’s meeting presented a stark contrast to the 2015 conference where countries adopted the Paris Agreement, which was hailed as a major milestone in international climate diplomacy.

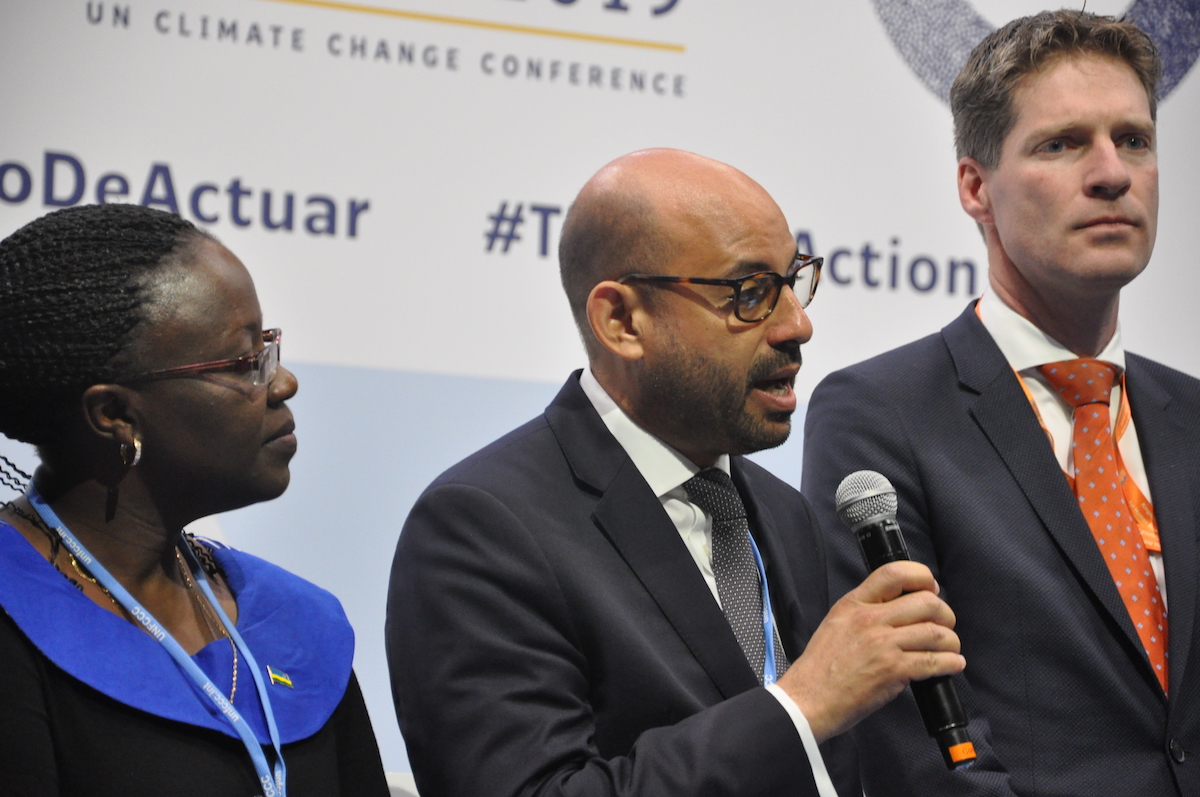

Photo by Doel Vázquez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Ramón Cruz

“Of course, at that time you had a very strong presidency in the French, [who are] champions of multilateralism, and you had Obama putting pressure on China and China already assuming the leadership of the world,” he said, adding that this year “we were seeing everyone going back to their places and acting in self-interest rather than collectively.”

In spite of the US government’s scaled-down presence at the COP25 — it didn’t set up a pavilion like many other nations — the country’s private sector was well represented.

The We Mean Business Coalition hosted panel discussions featuring business leaders who said they are working to fill the gap left by the US’ inaction on climate change.

The island states’ position also received unprecedented support from activists, scientists and non-governmental organizations. Most days, demonstrations were held both in and out of the convention center, and at one point a group of largely indigenous protestors was escorted out by police.

May Boeve, the executive director of the non-profit 350.org, noted the increased activism, but she described COP25 as a “victory” for the fossil fuel industry.

“After a year of climate strikes and the increasingly stark warnings of science, the only acceptable response to the climate breakdown was and still is for governments to commit to start phasing out fossil fuels immediately, including finance flows to this deadly industry,” she said. “This was the only real benchmark for success, and on this important test, once again, politicians have failed us.”

For AOSIS — which is often described as the COP’s “conscience” because of the vulnerability of its members to climate-related disasters like hurricanes, rising sea levels and flooding — the lackluster result was not for lack of trying.

As government ministers and other senior officials from nearly 200 countries bogged down during the high-level segment last week, the alliance called a press conference on Thursday — the fourth anniversary of the Paris accord.

“Parties are losing sight of the bigger picture as if there is no climate emergency,” said Simon Stiell, Grenada’s minister for climate resilience.

He also referenced a recent UN Environment Program report that measured the gap between countries’ climate pledges and their actions. UNEP found that countries would need to commit by 2020 to dramatically reducing emissions in order to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius. Even under the current Paris commitments — which aren’t being met — the world is on target to be more than three degrees warmer in 80 years, an increase that could force millions of people to move from coastal areas due to rising sea levels, the report stated.

Mr. Stiell said even two degrees is too much. “Our countries, as small island developing states, will be rendered uninsurable if we breach that 1.5 degree warming target,” he said.

He and other delegates stressed that island nations are already feeling the effects of climate change on a regular basis. On Friday, Marshall Islands Climate Envoy Tina Stege made a strong appeal during a plenary session.

“Just last month my nephew has been bedridden in a hospital… with dengue, which is something climate change has now pushed further north into our corner of the Pacific,” she said. “And two weeks ago members of my delegation arrived here in Madrid to news from home that roughly 200 of our people were evacuated from their homes as flooding hit our islands.

There were some pyrrhic victories for island nations. AOSIS welcomed a focus on oceans during the conference, which was described as the “Blue COP.”

The group also said progress was made during the negotiations on the text of Article Six about rules for a carbon market in spite of the “disappointing” failure of the countries to agree to a final version and adopt it.

“It’s not finalized, but at least we now have a clean text that we can work on and move it forward,” Mr. Fuller said.

Other achievements hailed by climate activists include a “Green Deal” reached by the European Union. Though Poland is exempt for now, the agreement pledges to legally require net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with a 50-55 percent cut by 2030.