Víctor Fajardo is having coffee somewhere in the Guaynabo metropolitan area. Before taking a sip, the former official of the Pedro Rosselló González administration warns that he has kept away from the media since his release from prison in 2013. “For the family,” he says. He spent 10 years behind bars at a federal prison and two under conditional supervision in his home for being involved in a million-dollar corruption scheme in the Department of Education (DE).

He agreed to talk about the Teacher Track program and the Community Schools, both part of the Educational Reform that he implemented (1993-1999). Two decades after his last days in office, he considers both initiatives as key pieces to rescue an educational system he describes as “a seven headed monster.”

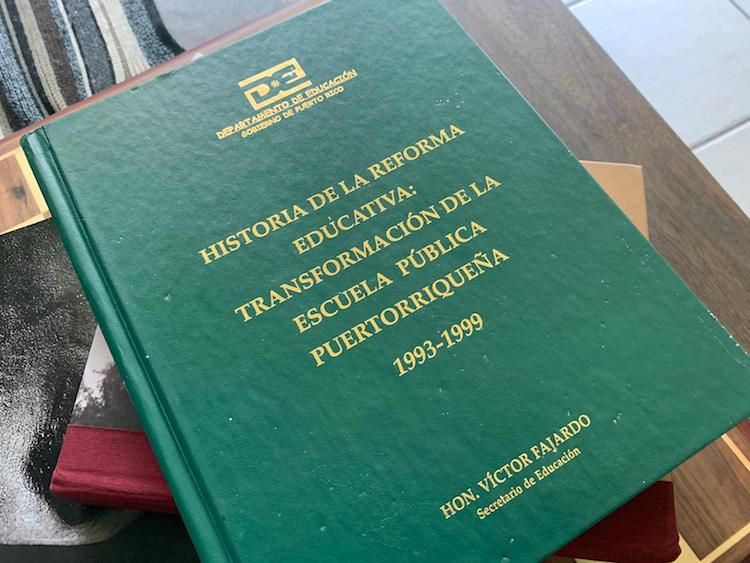

Fajardo prefers not to speak for the record about how, specifically, he came to the post of secretary. That happened shortly after the departure of his predecessors Annabelle Padilla Rodríguez and José Arsenio Torres, both named by Rosselló González. He had to implement the plan that was in place for Puerto Rico to start the new millennium with “a new public education system.” This is how the Educational Reform under Rosselló González was cataloged in a 404-page book with glossy pages that had a “historical purpose,” published in 1999 and distributed by the DE to each public-school teacher after printing tens of thousands of hardcover copies.

Fajardo does say that the DE “has strayed from its purposes” and that its “administration must be decentralized.” He administered the largest budget of all public agencies and knows what that represents year after year for the Popular Democratic Party (PPD, in Spanish) and the New Progressive Party (PNP, in Spanish) who have taken turns governing for the past fifty years. Through contractors and shell companies, he spearheaded the diversion of at least $4.3 million of public funds for personal and PNP purposes.

When asked about the Teacher Track initiative, that project under the Educational Reform that he led, which sought to establish procedures for promotions, salary reviews and parameters for professional improvement of teachers, Fajardo — the son of a teacher, himself a science teacher, a school principal and school superintendent at one time — said that the political priorities, and how things came about in the DE and the government after his departure, and the corruption scandal, were circumstances that “blocked the continuation of” the program. “In the four-year period after 2000, there was a change in administration, and [Teacher Track] was more or less cast aside.”

The CPI reported a week ago that the DE has a multi-million debt with the teachers who took advantage of Teacher Track, a law that has been paralyzed since 2014 and that has been breached, at least, since 2007. The investigation further reveals that the DE is unaware of the exact amount of money owed to those teachers and was unable to provide specific information on how many teachers, and since when, have they been waiting to get the money owed. The debt estimate is $4.3 million, as Interim Secretary Eliezer Ramos Parés informed the Senate.

“[Teachers] are owed a lot of money,” Fajardo said. He thinks it is more than the $5 million that Ramos Parés acknowledges .

“What is the debt he said? I doubt it. It’s more. Because since this began, many teachers became interested and participated in Teacher Track. And as they finished, some began to collect the salary differential, but after those first, the others still waited to be paid ,” he recalled. “Do you know how many teachers have left for the United States for a lack of financial incentives? It’s not because the grass is greener over there, it’s that everyone aspires to have a better salary. If you sacrifice, if you make the effort, you’re supposed to get some benefit.”

The Teacher Track was an “important” part of the Educational Reform, an initiative that Fajardo recognizes as a political-partisan project under Rosselló González, and makes it clear that at the same time, “it was a significant project” and that “it only needed continuity and development starting at the schools.”

With Sila Calderón’s arrival to the governor’s office in 2000, it was César Rey who was handed the administrative baton at the DE. The Teacher Track Act was amended in 2002 to include teacher librarians, school counselors, school social workers, vocational program coordinators, and instructional technology specialists. That same year, Fajardo was prosecuted by federal authorities along with 16 other people linked to the corruption scheme that diverted approximately $1 million of public funds to the PNP.

Fajardo said besides the corruption scandal, the problem with giving continuity and developing to the Teacher Track is that it was “not valued” within the framework of its potential in the 21st century. He is briefly silent when asked why. “There is a regulation that tells you how to put the Teacher Track in motion, [but] nobody is taking responsibility for making the necessary adjustments to make it work. Politics has eaten away more of the department than people think. They classified me as a political secretary. But I always did my job,” he says, with a copy of Act 158 in hand.

“Nobody has challenged the [Teacher Track] law, nobody has wanted to repeal the law because it is good and because of what it means for Puerto Rican teachers. Nobody touches it, but they don’t put it into practice,” he emphasized. “You make the effort, you study, you go from a bachelor’s to a master’s degree… That was rewarded while you were promoted. Just like it is at the University [of Puerto Rico]. University professors are ranked by levels, beginners start in the low rank and move up to become a professor. So, this law was there to motivate them [the teachers], prepare them, while keeping them in the classroom, so they wouldn’t have to, for example, become school principals to earn more [money],” he explained. “I’ll say it again, nobody dares to touch this law, nobody dares to. In other words, find yourself a legislator who says that they’re going to challenge that law. They would be attacked.”

He takes some time to look at the Act 158 documents, which now rest next to the cup of coffee, on the table.

“A second phase was supposed to happen, a second law [related to the Teacher Track] which included the school principals, supervisors, subject coordinators. The initiative stalled and it was nowhere to be found in the budget [the money to fulfill the Teacher Track]. In other words, what importance have the administrations that came after me given to this? Consequently, the teacher was left in limbo.”

The limbo that Fajardo refers to is the economic need, the money, the effort, and the time invested in preparing academically, and in the middle of a fiscal crisis, surviving the situation of not getting what was promised.

He was used for acts of corruption, he says

Although he initially established that he would only speak about the Teacher Track and insisted that he did not want to return to public life, nevertheless he spoke about the crimes that got him sentenced to several years in prison. He said they used him and that he knows very well what it feels like to be left alone and without influence.

“I was naïve and didn’t realize that they were using me for an economic scheme, people who came to me with great projects and what they were doing was fabricating, conspiring, you know. I didn’t have that malice. When they pointed the finger at me, what they were asking me was that I speak up to accuse people who gave me the order to do that [divert, through bribes, approximately $1 million of federal funds for the PNP coffers, for example]. I said no because I’m not like that. If I did, I admitted responsibility and did what I was assigned to do. Because what am I going to do blaming others? That doesn’t work.”

Although he did not want to say the names of those who, supposedly, gave him direct orders, he assured that the suffering he has experienced “is immeasurable.” He prefers not to clear anything up, even though he says he is not happy with being remembered as the ringleader of an episode of corruption that, in his opinion, is discussed “without the real details” that “would make it different.”

“I was in prison for 12 years [10 incarcerated and two under conditional supervision] for a sequence of things that, because of bad judgment and lack of malice, when the prosecutors identified me, I couldn’t say no. Because yes, I was in the middle of it all.”

“My family suffered a lot, a lot. We had an extremely difficult time. But I tell you one thing, I assumed responsibilities because that’s how I am. If I was there and I was the head of the Department of Education, I would take responsibility. But the department wasn’t missing a penny. And I tell you that upfront. Everything became a political act to find the scapegoat and that everyone looked good, except me.”

A return to Community Schools?

Fajardo insists, 20 years after his turn at bat, on the decentralization of the Department. He says that current responses to school communities fall short and that given that reality, “which is reflected, for example, in the conditions of schools and the abandonment of schools,” it becomes “almost impossible” to meet the needs of teachers under the current administrative model.

“When the Community Schools were created as part of our Educational Reform, they were the best possible mechanism to decentralize the system,” he assures. “A dollar that came to the Department, as an allocation, did not have to go through all the administrative and bureaucratic steps so that they could buy a pencil in the classroom. That dollar was assigned to the school, and they oversaw that this dollar was used correctly,” he adds.

He does not deny that “politicking” and administrative irresponsibility existed under this model. But he believes that the school environment was more productive than it is now, “because it was on par with the environment of the communities.” “It was better than what there is now, that had to be improved by strengthening the Community Schools.”

Former Education Secretary, Rafael Aragunde, is not so optimistic. Even though he supports Community Schools “as an alternative,” and something he thinks of as “a great initiative aimed at guaranteeing autonomy to schools,” he is not convinced of its effectiveness.

“The experience that I had is that, even in those instances, good friends collude, and support people committed and identified with the party or political movement to which they belong. In other words, every attempt that has been made here to depoliticize after bipartisanship, from 1968 to this date [2021], have been resounding failures. We’re facing a culture that has abandoned its best practices,” he said in a discussion organized by the CPI on the current situation of public education in Puerto Rico. Aragunde headed the DE when teachers received the last raise ($250) to their base salary, which is currently $1,750 a month for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree.

According to Fajardo, what had to be done was “to supervise or prepare that administrator [school director], that school environment [through the School Council], to do things correctly. That isn’t difficult. Even more so now that there are fewer schools. When I headed the Department there were approximately 1,570 schools. There were about 627,000 students. I’m talking about the year 2000. There aren’t even 300,000 students now.”

He believes that the closure of schools, mainly under the prior administration of Julia Keleher and Ricardo Rosselló Nevarez, happened without considering the community. “That was crazy. You see that now Governor Pedro Pierluisi is talking about schools that were closed to see if they can be reopened.

Political hand-off

“[The Teacher Track] was a good investment,” said César Rey when asked about this initiative that today translates into a multi-million-dollar debt for the DE with an unspecified number of teachers. “The shame is that, like everything else, the administration changes, the federal funds change. It starts to crash.”

“I think it was the first time that we recognized a lack of training , which probably had to be fine-tuned, no doubt. It was my turn to implement it. I even had to amend it. I’m aware of the number of teachers who benefited from this process. That it later fell short of their expectations, we would have to look into that to see what went on and why it happened. The worst thing is that it stopped,” he said.

Rey said that, during his tenure, the factors that conditioned the DE’s economic reality surfaced after the Fajardo corruption scandal and the impact of the federal No Child Left Behind law. Imposed by the George W. Bush administration, this law promoted a greater influence and participation of the private sector in the provision and administration of services in the agency, a phenomenon that, in an overwhelming way, strongly federalized the DE, both from the economic point of view, like conditioning the evaluation methods without a contextualized foundation of the realities of the Puerto Rican student.

“The great tragedy, again, is that cronyism, partisanship, the backing of the parties in power, swallow that money in million-dollar consulting contracts for projects that end in nothing, consulting projects and tutoring by people who fully lack credibility. Some are on trial; others are in prison as we speak. People who, at the time, saw the Department of Education as the goose that laid golden eggs and acted on it. It seems like a huge contradiction. A debt to teachers, inadequacies for teachers and on the other hand an island that receives a lot of federal money for precisely that, but that doesn’t get to where it should go. And we all know horror stories.”

Fajardo, meanwhile, assures that he still walks in a teacher’s shoes. “I never took them off,” he says, and recalls his time in jail and his experiences prior to “Operation Blackboard,” the name by which the federal investigation of the case was known internally.

When he finishes his coffee, he says goodbye assuring that “he would like to help,” that he “would like to intervene” in the island’s educational affairs. “But no, because that’s going back to public life again.”

José M. Encarnación Martínez is a member of Report for America.