The question came to my mind five years ago: how many Puerto Ricans are incarcerated in the United States? At the time, in 2018, I was investigating the Government of Puerto Rico’s failed attempt to transfer incarcerated people from the custody of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to a private prison in Mississippi.

But it wasn’t until 2020, when I moved to Philadelphia, during the pandemic and the racial protests over the murder of George Floyd, that I began to investigate the matter. First, I did a light search on the internet which returned no results. Then I made some calls. And so, I began to explore a subject that turned out to be extremely more complicated than I expected.

On Friday, August 21, 2020, I called Jan Susler, a Chicago attorney who defended political prisoner Oscar López Rivera. I wanted to know if she thought it was possible to get data on Puerto Ricans in US prisons. She told me that “on the federal issue, the Department of Justice has a data department, but I don’t know if it includes a separate category for Puerto Ricans.”

I had already made inquiries in that department’s databases and apparently that category did not exist.

Susler referred me to Carmelo Campos, a lawyer, professor of penology at the Colegio Universitario de San Juan, and a member of the “Coalition Against the Death Penalty.” In April 2020, Campos had published a study on Puerto Ricans sentenced to death.

The same day at 3 pm, after speaking with Susler, I called Clarisa López, daughter of Oscar López. “That’s indecipherable,” she said when I told her what I was looking for. She offered to put me in touch with Oscar López, to see what he thought, since he had more experience. “I just called him, and he didn’t answer, sometimes he doesn’t hear the phone… Maybe he’s painting, or in a meeting.” She agreed to give him my number to call me.

Then I called Carmelo Campos. The article that he had published in 2020 about Puerto Ricans sentenced to death in the United States had the following data: there were 20 Puerto Ricans incarcerated in the United States (19 state and one federal), distributed among six states. All were sentenced to death between February 2013 and April 2020. The majority were in Pennsylvania (9), followed by Florida (6), 1 in California, 1 in Georgia, 1 in North Carolina, 1 in Texas, and 1 under federal custody.

“In the case of death row, it’s easier [to find data], because there’s a quarterly publication from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which has a summary of all the people who are on death row. And in addition to that, it classifies them if they are white, black, Latino, others… Even if that’s it, it’s helpful,” Campos said on the call.

But do they have the category for Puerto Ricans? I asked him.

“No. The most they have is Latino, it can be Mexican, it can be Cuban, Salvadoran, etc. It’s problematic, what we did, since it was a much smaller population, is that we concentrated on some states that we knew had a higher volume, mainly on the east coast, Pennsylvania, and Florida. And then we sent questionnaires to them directly, we used information from the press, we used information from the courts, from relatives who had contacted the Coalition. The sources were very varied.”

In that conversation, I realized that my research goal was too ambitious: to find out how many Puerto Ricans are incarcerated throughout the United States. I was going to have to do something that now seems obvious: reduce the sample to include only the states with the largest Puerto Rican population.

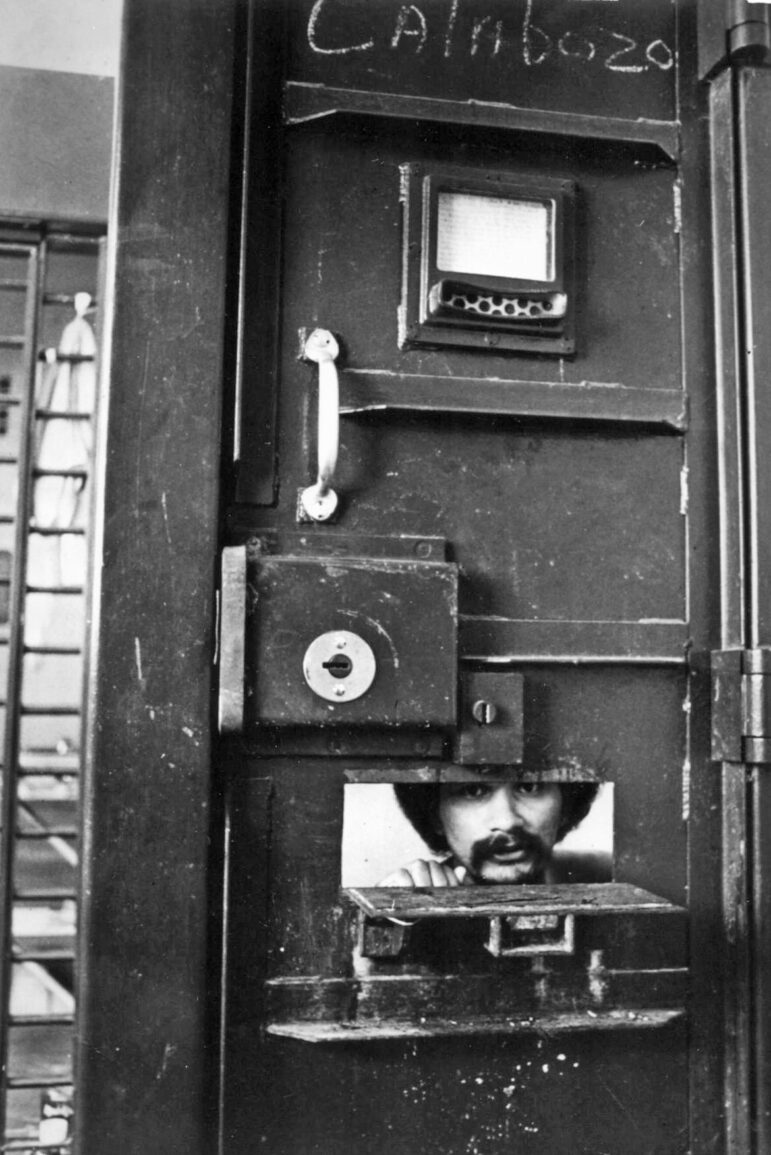

A conversation with a former political prisoner

Oscar López called me that same day at 5:14 pm.

Oscar López was released from prison in 2017, after President Barack Obama commuted a sentence that condemned him to 55 years in federal prison. He was born in San Sebastián, Puerto Rico, and at the age of 14 he moved to Chicago, Illinois. In 1988 he was accused of seditious conspiracy (attempt to overthrow a government) in favor of Puerto Rico’s independence. He served 36 years of his original sentence, during which he was transferred among federal prisons in Arkansas, Illinois, Colorado, and Indiana.

Photo by Juan Alicea | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

When he called me that afternoon in late summer of 2020, Oscar López listened in silence to an explanation perhaps too long about my investigation of Puerto Ricans incarcerated in the United States. He then went on to calmly tell me what he thought and what he knew.

“The percentage of Boricuas, when we compared per capita, was high, there were many Boricuas incarcerated throughout all the prisons, from the east to the west. There were Boricuas, for example, in Florida, in the southern states there were Boricuas, in the northern states there were Boricuas. From east to west and from north to south there were Boricuas. There were Boricuas in Minnesota and there were Boricuas in Arkansas,” said Oscar López.

And incidentally, he described another of the complexities when it comes to identifying Puerto Ricans in US prisons.

“Look, you’re going to find, you’re definitely going to find Puerto Ricans who are half Puerto Rican and half Mexican, you’re going to find half Puerto Rican and half indigenous. I was in prison with a guy whose father was Puerto Rican, and his mother was indigenous. Many times, you will enter a prison and you will find Puerto Ricans from Hawaii. The mixes are somewhat great. It’s quite, quite complicated. Because the Latinos that are classified, aren’t identified as Puerto Ricans.”

But he also gave me a clue.

“In every prison where there are Puerto Rican prisoners, if they were born in Puerto Rico, they have to have the date of birth as Puerto Rican.” But he warned me: “What often happens is that, for example, a Puerto Rican may have been in the United States all their life…they send them to prison, they won’t come out as a Puerto Rican, they’ll come out as someone whose birth certificate is in the US. It’s a little difficult to be able to identify Boricuas that way.”

It means that if the corrections departments register the place of birth of their inmates, I could request the data, at least, of the people born in Puerto Rico that they have among their population. Another detail that I hadn’t thought of: Oscar López was incarcerated in federal prisons. When someone is in that custody, they’re prone to constant transfers between different states. So, it would be better to focus, for now, only on those incarcerated in state custody.

“The way I identified Boricuas was almost always because they were in groups… For example, there’s a group called Los 27, there are Los Ñetas in the United States… Because in the ‘80s, ‘81 there were [in Puerto Rico] all those fights between the two groups [at the prisons] they ended up taking the leaders and most of them to the United States,” Oscar López said.

Photo by Freddie Toledo | Claridad

Los Ñeta or Movimiento Pro Derecho de los Confinados, was an organization whose idea was to “form a strong association of all inmates, committed to promoting the rights of prisoners and guaranteeing their dignity and safety,” according to historian Fernando Picó. Los Ñeta was led by the enigmatic Carlos Meléndez Torres alias Carlos La Sombra, who went to prison at the age of 17 for drug cases. Being in prison and witnessing abuses and human rights violations by the Department of Corrections, in addition to advocating for the rights of inmates, he became a poet and political activist for Puerto Rico’s decolonization. Between 1979 and 1981, there were violent altercations between this organization and its rival, Los 27 or the June 27 Movement, a conflict that resulted in more than 50 deaths, according to Picó. In the 1990s, individuals incarcerated in the United States claimed affiliation with the Ñeta.

The history of the political prisoners linked to decolonization movements is perhaps the best-known part of the history of the Puerto Ricans imprisoned in the United States. From nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos, sent in 1937 to the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, the members of the Nationalist Party arrested in the 1950s for the attack on Congress, in the 1970s those of the Frente Armado de Liberación Nacional, and in the mid-1980s, those linked to the Boricua Popular Army-Los Macheteros, among them artist Elizam Escobar and Oscar López.

Puerto Rican resistance in prisons

A lesser known story is that of the Boricuas from the diaspora who have been linked to other forms of resistance inside US prisons.

Between September 9 and 13, 1971, what is known as the Attica Rebellion, broke out in the Attica State Prison, New York. Around 1,281 prisoners, out of a total of 2,243, participated in the rebellion that began with the taking of 42 prison employees hostage, demanding better living conditions and political rights.

In that incident, 33 prisoners and 10 guards died. All but one guard and three prisoners were shot dead by the authorities. At that state prison, on the northwest border of New York, its 2,243 inmates were mostly urban, low-educated, African American and Puerto Rican youth, according to historian Heather Ann Thompson.

One of them was a 17-year-old named Angel Martinez, who had become addicted after using heroin to try to ease the pain of polio. When he committed a crime to satisfy his addiction, the judge sent him to Attica.

“Ending up in this particular New York state prison was especially rough on prisoners like Martinez since they could neither speak nor understand English. There was one Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican correction officer on staff, but his fellow officers insisted that he only use English with the men in his charge,” Thompson points out in her book “Blood in the Water: The Attica Uprising of 1971 and its legacy.”

Thompson adds that the prison doctors, who did not speak Spanish, were particularly insensitive to the medical needs of the Puerto Rican population. Also, everyone in Attica had to work, but African Americans and Puerto Ricans were paid less than whites.

And although all prisoners were theoretically subject to censorship in the mail, Puerto Ricans and African Americans suffered the most from that policy. They also had stricter rules for visiting relatives. As a result of the riots in which Puerto Ricans, whites, and blacks banded together, the Department of Corrections in New York made some changes in its policies. But between the 1980s and 1990s the changes that had been implemented ended in nothing, according to Thompson. Attica Prison continues to work as a maximum-security prison.

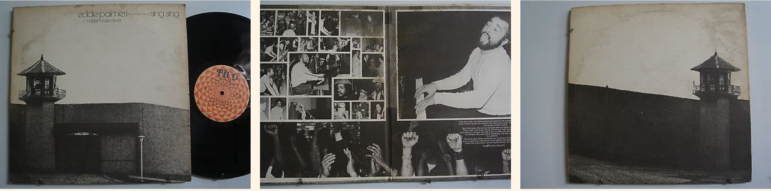

Image from Roots Vinyl Guide

Less than a year after the Attica riot, in the early winter of ‘72, pianist Eddie Palmieri and his Harlem River Drive Orchestra brought a concert to Sing Sing, a maximum-security prison in Upstate New York. There the orchestra played, in front of a mostly black and Latino audience, songs like “Pa la Ochá Tambó” and “Muñeca.” Near the end, there was an intervention by Afro-Boricua poet, and member of the Young Lords, Felipe Luciano, who proclaimed: “So many times we have the kind of conflicts that make us more apart than we are as a people, and we know as a people, Black and Puerto Ricans, have their destinies out before, but we are going to keep on moving and build a nation for all of our people.”

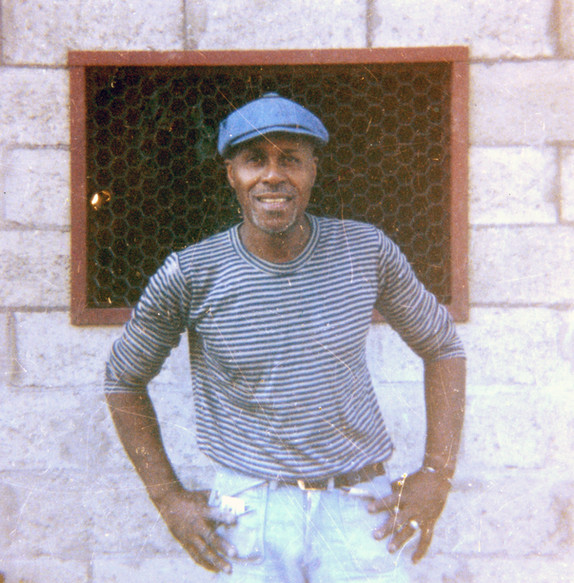

Recently, literary critic Julio Ramos rescued the figure of Martín Sostre. He was an Afro-Puerto Rican, born and raised in New York, a bookseller, writer, and activist defending the constitutional and civil rights of prisoners. In 1968 he was accused of inciting a riot and other offenses against public order in the city of Buffalo during the 1967 race riots, Ramos says.

Courtesy of Sandy Shevack | Martin Sostre Institute

That initial indictment against Sostre was dismissed for lack of evidence, but the bookseller was sentenced to between a minimum of 30 years and a maximum of 41 years in prison for an alleged sale of narcotics from his small Afro-Asian bookstore, located on one of the main arteries of the black neighborhood of East Buffalo. The police raid that resulted in Sostre’s arrest and ultimately destroyed what remained of the flimsy bookstore took place two weeks after the riot in June 1967.

The prosecution’s main witness, Arto Williams — the man who allegedly bought Sostre a $15 dose of heroin at the bookstore — recanted his accusation in 1972 and publicly confessed that his sworn testimony against Sostre had been set under pressure from the police and the offer of immunity in another drug case against him.

Still the court decided that Williams’s confession was not credible and ruled against Sostre. Sostre was not released from prison until 1975, when his sentence was commuted by an executive pardon from a liberal New York governor, Hugh L. Carey, according to Ramos, “susceptible to the penal reform trend promoted by civil rights advocates following the Attica massacre, and pressure from multiple solidarity and support groups, including the top brass of Amnesty International.”

Philosopher and activist Angela Davis mentions that Assata Shakur, a black political prisoner, member of the Black Liberation Army, convicted of killing a highway police officer in New Jersey, was subjected to unusual cruelty. And her account of that experience, according to Davis, mirrors that of other women incarcerated in the United States, especially Black and Puerto Rican women.

Shakur met pro-independence political activist Lolita Lebrón in prison and considered her an inspirational revolutionary example. Among the many mentions that Shakur makes about Puerto Ricans in her autobiography, one especially reflects the cruelty to which they were subjected: “one night they brought a Puerto Rican sister. She had been so badly beaten by the police that the matron in charge that night did not want to admit her. “I don’t want her to die on my shift,” the midwife repeated. Days passed until the [Puerto Rican] sister was able to get out of bed.” Today Shakur is on the run from the authorities.

Resuming the investigation

Despite all these stories, which are part of the same story where colonialism, racism, the prison state, and the Puerto Rican diaspora intersect, the only study that attempts a joint analysis of the conditions of Puerto Ricans incarcerated in the United States is one about prisons in New Jersey and it happened in 1977.

It is called, “A Profile of Puerto Ricans Prisoners in New Jersey,” written by Robert Joe Lee, as a master’s thesis from the Rutgers University Graduate School of Criminal Justice. The study is based on a survey of 93 “Hispanics” from state jails, juvenile and county detention centers in New Jersey. Of the 93 surveyed, 85 were Puerto Rican. The thesis concludes, among other things, that the New Jersey correction system needed more integration services. Especially for young Puerto Ricans who had recently migrated to the United States and ended up in jail without knowing English.

After the first searches for sources and the initial calls, I continued working on other issues until I abandoned the investigation of Puerto Ricans incarcerated in the United States. But I kept thinking about it constantly. Then, on September 21, 2022, I emailed the Florida Department of Corrections. I asked if they had the number of Puerto Ricans who were in state jails.

They responded on September 23, indicating that I should call a telephone number. The call was very choppy, as if they were speaking to me from a remote area. That they gave me the information so quickly took me by surprise. The person who helped me said, wait a minute. I waited listening to static and praying the call wouldn’t be disconnected. When she came back, she told me that there were 1,201.

I still submitted a formal request for information to confirm and have more details. Then I made the same requests to Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, the six states with the most Puerto Ricans. Florida made me send a money order to pay for the application, Massachusetts made me fax the application, New Jersey refused to provide the information and I had to appeal, only to get incomplete data. But the investigation was finally underway to answer the question of how many Puerto Ricans are incarcerated in the United States.

The result was incomplete and shows that US corrections departments have an inefficient classification and data collection system.

But I hope that at least a window has been opened to begin to investigate a world that has been in darkness for a long time. Each Puerto Rican history book and each media agenda that does not consider the Puerto Rican prison population in the United States will be incomplete. Because prison as a system of repression is another of the defining links in the history of displaced people and migrations fostered by colonialism. Making the prison population visible is making visible a power, the power of the prison state, which ranges from the police, judicial and correctional system, and which must be subject to constant public scrutiny.

Próximo en la serie

4 / 8

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.