It’s a Friday in September, and the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA, in Spanish) building is closed. Two official vehicles are parked in the driveway of the structure that looks abandoned from the road. One of the vehicles is covered in dust and spiders. A small off-road vehicle is also abandoned at the back of the building, where there are broken buoys, rusty anchors, and a decaying power plant. In the yard, there is a jet ski and another official vehicle that are of no use.

Culebra’s beaches are among the best appreciated by global tourism. They appear in international rankings, as well as, in the Puerto Rico Tourism company’s guides and marketing campaigns used to boast of Borinquen’s paradisiacal wealth. Besides the marketing and propaganda that the government uses to attract tourists, in Culebra, there is no DRNA vessel to supervise the coasts, its natural reserves, or keys. There is no one to supervise or respond to reports of environmental violations, both at sea and on land.

Nearly a hundred illegal docks, the removal of land without permits, the installation of permanent platforms in the ocean, constant anchoring of boats in prohibited areas such as corals, illegal fishing in reserves, and discharges of used water are part of the violations that are impacting with impunity one of the most pristine and valuable areas of Puerto Rico due to the negligence of the DRNA, a Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) investigation revealed. The government doesn’t even fulfill its legal responsibility to collect the tourist tax established almost two decades ago to have a fund for the environmental protection of the island municipality.

“What happens in the keys, the people who arrive on private boats and everything that happens at sea, is practically uncontrolled,” says Neil Romero, executive director of the Culebra Conservation and Development Authority (ACDEC, in Spanish). “There’s no surveillance, except for the times when the maritime police come by. And [the U.S.] Fish and Wildlife [Service] also occasionally comes by. But [there is] nothing permanent here, that we can say a boat departs from here every day to patrol.”

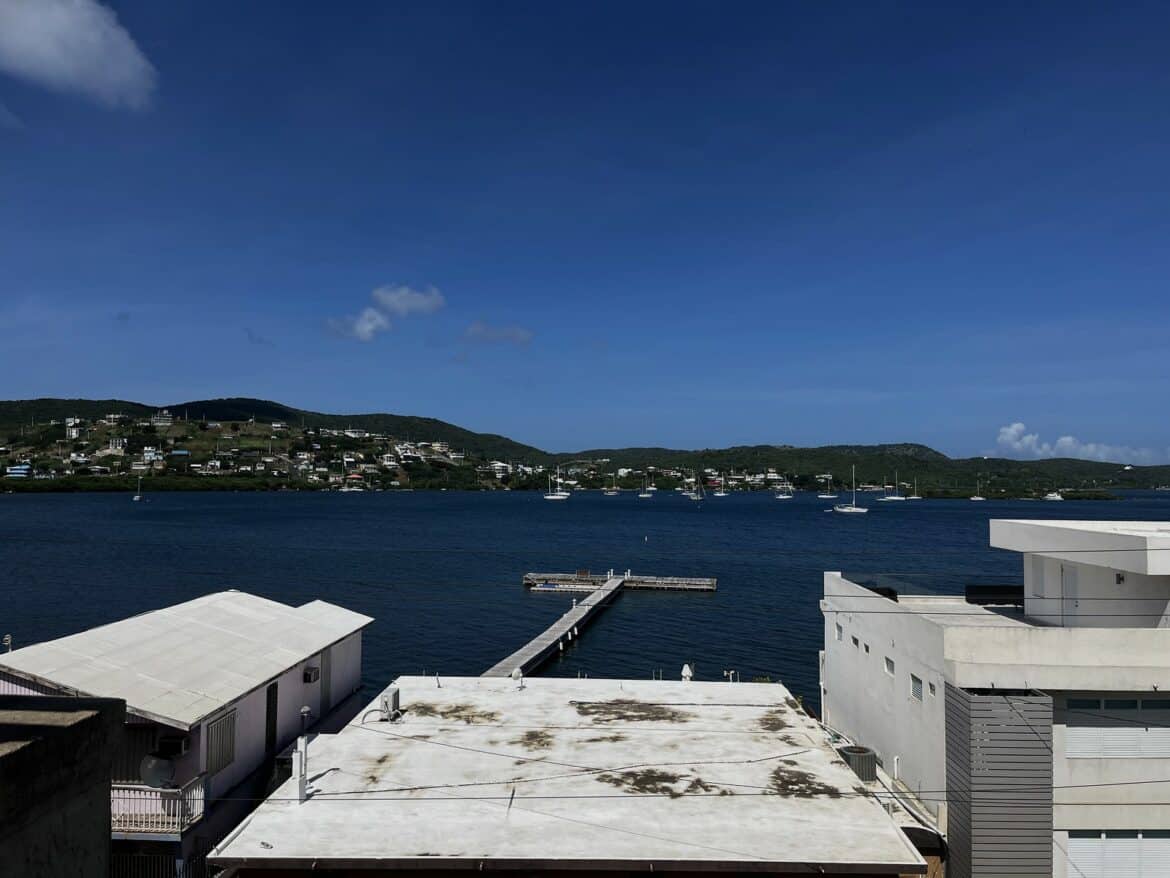

Photo by José Encarnación Martínez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Culebra is the only municipality in Puerto Rico that has a public corporation with the characteristics of ACDEC, a protectionist mechanism created through Act 66 of 1975 after the U.S. Navy departure left Culebra, where they carried out military practices for four decades. The measure recognizes “the unique characteristics of this Island Municipality” and seeks to establish “public policies framing the conservation and development of Culebra.”

But today, the duties of this public corporation, attached to the Municipality of Culebra, are more than limited, mainly due to the DRNA’s inaction, which does not respond to complaints of environmental violations there. ACDEC has the obligation to ensure the sustainable development of Culebra, and although it has the authority to enforce the law, it has eight employees who are not distributed to assume surveillance tasks but placed in administrative roles or to oversee the public beach, its director said.

Although Act 66 establishes that “no agency will approve any private work or project in relation to Culebra Island that conflicts with the plans and policies formulated and adopted” and that “a favorable endorsement must be obtained” from ACDEC before each development, there are unpermitted developments and other projects that get the approval of the Office of Management and Permits (OGPe, in Spanish) without ACDEC’s initial approval, as the measure establishes.

The consolidation of agencies under the Department of Economic Development and Commerce (DDEC, in Spanish) during Ricardo Rosselló’s tenure, Act 141 of 2018, established that “the duties related to permits are transferred to the DDEC so that the policies and procedures for the conservation, development, and use of land on said Island Municipality can be standardized so that they are consistent with the public policy of the government and the initiatives promoted at the state level.”

The problem of permits has been dragging on for a long time.

“My people cannot go into any area to question,” Romero said. “People call us and we [ACDEC] go, we take photos of what’s happening, but that’s where it ends. If a formal complaint is filed, then that complaint is sent to the DRNA office, and it’s their responsibility to handle the situation. After doing this, we [at ACDEC] cannot do anything. We would like to stop them, but it’s impossible.” Although ACDEC has the power to issue cease and desist orders, it does not have the authority to arrest or prosecute environmental law violators. Romero did not specify how many complaints ACDEC has filed at the DRNA.

An example of the consequences of the limbo status that Romero points out is right in front of Melones Beach, just a few blocks from the ferry terminal and the urban center. Despite not having an endorsement from ACDEC, heavy machinery deforested a basin, despite it being a vulnerable area due to its proximity to the shore. No sedimentation control barriers were installed. This caused the sediment to end up in the water after the rains, becoming a threat to the marine ecosystem. A sign placed in the area identifies Ricardo Vázquez González and surveyor José Trinidad as the owners of the land. “Earth Crust Permit,” reads the notice. It also says that the request was for “cleaning of a layer of vegetation.” This scene is repeated in different parts of Culebra.

Years of inaction

For years there has been no control over what is done on the lands of the Municipal Island, according to a report that analyzed the granting of permits in Culebra between 2014 and 2021 drafted by the biologist Alfredo Montañez Acuña, facilitator of the Canal de Luis Peña Natural Reserve Collaborative Management’s Community Advisory Board.

The analysis attests that more than 25% of the permits granted in this period may be illegal. These permits were specifically granted to projects that, according to the Regulations for the Environmental Assessment Process, would not have a significant environmental impact. These projects are known as DEC or “categorical exclusions,” and do not require an in-depth environmental impact analysis. The OGPe received at least 262 requests of this type between 2014 and 2021 for 168 land registry numbers in Culebra, according to the report presented to the municipal administration. Approval of each of the potentially illegal DECs took, on average, 2.5 days, according to the analysis.

Likewise, it is noted that the 183 potentially illegal approved categorical exclusions were managed in at least 43 different land registry numbers.

Two years ago, the Culebra municipal administration, together with local, federal, and nonprofit entities, met with the goal of stopping improper developments through categorical exclusions. The claim was that OGPe stopped granting permits by way of categorical exclusion and that the DRNA delegate to ACDEC and the Municipality, the administration of the maritime-terrestrial zone, as well as the lands reclaimed from the sea. This claim, despite having been presented at that interagency meeting with representatives of OGPe, as well as the National Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), has yielded no results.

“The results show that the OGPe is still approving, or continues to allow, categorical exclusions (DEC) approved without meeting the criteria established by the DNA’s administrative order. These DECs were mainly approved for construction, followed by use permits, reconstruction or remodeling, and segregation of lots,” according to Montañez Acuña’s comments, which resonate with the example of Playa Melones two years later, in the proliferation of illegal docks and the rest of the environmental problems that are not addressed. Now, Montañez Acuña reaffirms his opinion from two years ago. “A structure [ACDEC] whose principle was to prevent these things from happening in Culebra has been undermined […] and they continue to undercut it, to the extent that decisions are made without considering the true impact that the initiatives can have,” he said.

Photo provided by community leaders

Most of the construction projects noted in the 2021 report were residences, trailers, or campers. Categorical exclusions were also approved for the construction and repair of non-compliant docks. At least 44% of the potentially illegal categorical exclusions approved between 2014 and 2021 in Culebra were 50 meters from the demarcation approved in 2018 and 60% at the same distance from the coastline.

Oversight that doesn’t work

A technical inspection that the DRNA carried out in November 2022, in response to an environmental impact complaint in Playa Dátiles, exemplifies the level of anarchy in Culebra in terms of protecting natural resources.

“The impacted location doesn’t have an OGPe permit, a sign, or any indication of being a project approved or endorsed by ACDEC,” reads the report. It states that it’s a plot with unique natural resources and that “part of the impact occurred in the Maritime Terrestrial Zone.” In fact, the practice of using heavy machinery and completing vegetation removal work happened at that time without any pushback from the government, as it happened recently in Playa Melones.

The DRNA report also recognized that important endangered and protected species at the state and federal levels could have been affected without leaving further evidence in the area.

“Sedimentation caused by land movement can directly affect critical habitat ecosystems for the green or white turtle (sea turtle) by disturbing the species Thalassia Testudinum (turtle grass) and Syringodium Filiforme (manatee grass),” the document states. Since 1998, the waters surrounding Culebra have been designated a critical habitat for the green turtle.

Likewise, “at the site, terrestrial material was extracted from a nearby hill to fill a wetland that gives access to the area” and the officer who wrote the report said he witnessed the damage to the ecosystem “that came weeks or months after the impact described in this report.” The damage was documented, but not prevented.

“We need things to be done as the [territorial] plan dictates,” insists Romero, who assures that the current situation “is very frustrating,” because violations happen without consequences. “As soon as there is someone with land to sell, a buyer immediately appears, and many impact the land irresponsibly, as if this were no man’s land.”

A boat adrift…

At the time of the CPI’s visit, there wasn’t a single DRNA ranger in Culebra. After the visit, three cadets graduated from the ranger academy to provide services on the Municipal Island. It is the first time this year that there are DRNA rangers stationed in Culebra since Romero took over as executive director of ACDEC in February. His biggest concern right now “is being able to contain everything that is being done clandestinely.” “It’s a lot,” according to the official. He recognizes that there is no inventory of illegalities or developments that fail to comply with the law. ACDEC is limited to approving or denying endorsements. They do not have a list of complaints submitted to the DRNA. The lack of personnel limits them in that aspect, as he says, even though this public corporation has more employees than the DRNA on the island municipality.

ACDEC operates with an annual budget of $500,000, of which almost $200,000 goes to payroll and related expenses.

Besides the illegal constructions, boats are anchored on reefs, in protected areas, and the discharge of used water into the bay has been normalized. The construction of illegal docks is also out of control.

Given the inaction of government agencies, a group of community leaders worked on an inventory of anchor buoys. Of 93 anchor buoys that were installed over the years in the waters of Culebra, as of September, 58 had been lost. Those that remain, for the most part, are in poor condition, according to the inventory compiled by the community. This causes illegal anchoring on reefs when hundreds of boats arrive in Culebra, as well as the entry of vessels into prohibited areas and groundings.

Contrary to existing protocols in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where annual fees between $10 and $20 are charged according to the size of the vessel, there are no such regulations in Culebra. There is no fee to anchor in the waters of Culebra and no reports of stays in the waters are written up. The boats arrive, anchor, and can stay for years, and nothing happens.

According to the inventory of anchor buoys carried out by the community through September, there were 10 anchor buoys on Carlos Rosario Beach in Culebra, and only two are left. In Tamarindo Grande, there were nine anchor buoys and only three were left. In Playa Tamarindo, there were 11, and three were left. Six were installed in Playa Melones and only one remained. In Punta Soldado, there was only one of the two anchor buoys that were there. In the Luis Peña Reserve, there were supposedly six, and two remained. In Dákiti, 22 were counted and nine had been lost. Between Almodóvar Bay and Punta Vaca, four of 13 anchor buoys were lost. And in Culebrita, of 14 anchor buoys, only one remained.

Anchor buoys are lost due to natural causes, such as hurricanes and storm surges, as well as, excessive use, lack of maintenance, or pressure from large vessels that are not supposed to anchor in them and that sometimes remain for months, and even years without the DRNA acting.

“The Municipality of Culebra has no type of jurisdiction to deal with this issue [of the anchor buoys],” said Mayor Edilberto Romero Llovet when asked about the status of the maintenance of the anchor buoys. That responsibility for the buoys belongs to the DRNA, which, in August, one month before the six-year anniversary of hurricanes Irma and María, told the community that they would visit Culebra at the end of September “to learn exactly what anchors needed to be replaced.” They said, however, that the replacement of each previously installed anchoring and mooring system requires permission from federal agencies. The same was also said two years ago at the Interagency meeting, but nothing happened.

“We got the approval of a permit from the USACE to reinstall a large part of the mooring buoy systems installed in Fajardo and Culebra. Additionally, a claim was submitted to FEMA for mooring buoys and anchoring systems that were affected by hurricanes Irma and María. The claim to FEMA is very far along and we hope for approval soon,” said a letter from Edwin Rodríguez, a biologist from the DRNA Marine Resources Division.

“In addition, with the information collected during the week we visited Culebra, another permit will be issued [to carry out maintenance work at sea]. Work is underway at the U.S. Corps of Engineers to replace mooring buoys that aren’t covered under the recently approved permit. Culebra anchors have been installed for many years and have been overused by recreational boats. The buoys are for daytime use and some boats spend the night, and others usually raft, actions that cause metal fatigue and eventual breakage of the anchor and mooring system,” said Rodríguez.

Meanwhile, the Mayor said the problem of anchoring and discharging used water in the bay has been going on for decades. “They come, they stay there to live, and they unload right there. We don’t have manpower and we have to find the money. “There are ideas, but there are no resources to execute.”

The mayor chairs the ARDEC Board, a body to which Neil Romero responds as executive director. “The problem is that the processes are very slow, due to bureaucracy,” the mayor said, recognizing that he “very much needs” to install anchor buoys in the Luis Peña Marine Reserve. He recalls that he met with former DRNA Secretary Rafael Machargo. “We had meetings with Machargo so that the Culebra Conservation and Development Authority and the Municipality had the jurisdiction to work with the illegal docks and buoys. It came to nothing because we didn’t get a response,” the mayor said.

The mayor, who was a DRNA ranger for about 25 years, asked for a $2 surcharge on the ferry fare, which is currently $2.25, “for anyone who visits Culebra and is not a resident.” He said that the surcharge “is already happening .” He hopes that the private company operating the ferries, HMS Ferries will start collecting the fee from visitors “before the end of October,” and then, the Integrated Transport Authority (ATI) will get the funds “to transfer it quarterly to the town’s special fund.” The mayor assured that the charge will only apply to those traveling for tourism purposes. “The charge will not apply to people who travel to work,” or live in Culebra, he said.

The money from that special fund would go to projects for the conservation and environmental protection of Culebra. It’s nothing new, it’s enforcing a law that dates back 19 years and came to nothing. Governor Sila Calderón signed Act 293 of 2004 “for the purposes of financing the environmental preservation and maintenance work of the Island of Culebra, establishing a public policy of ecological preservation, structuring a citizen education program on Culebra’s environmental value, and enabling a program of behavioral standards for visitors to Culebra.”

Every year, more than 500,000 tourists visit Culebra. At least $20 million could have been raised for this concept since 2004.

“I can’t wait for that law to go into effect at the end of October,” said the municipal leader. “Because I can create municipal environmental police that enforces regular laws and execute on illegal constructions, docks, and illegal movements of soil,” he said.

The mayor said the new Culebra Public Order Code, approved last May, empowers the police to issue fines if something is being done without permission from ACDEC. However, this has not been put into effect in the past four months. “We hope to have some control over that. First, a warning ticket will be issued [to the person who is acting without approval from ACDEC].” Culebra didn’t have a Public Order Code. “Now, with the code, I can call the police and issue fines,” said the mayor, emphasizing that this is a way to begin to contain the different environmental problems.

Illegal docks proliferate

The mayor participated in the dock inventory in Culebra when he was a DRNA ranger. He remembers that just over 100 docks were counted before Hurricane Maria. After the pandemic, the number of docks has increased by more than 46%. The CPI carried out a count through a satellite image and identified that by 2015 there were at least 114 docks. Through February 2023 that number increased to 167.

“The problem there is environmental because the vast majority of these docks don’t comply with environmental laws,” said the mayor. “[Many of those docks that were built without the approval of the authorities] don’t allow natural light to enter the water, they are built on mangroves, the lights are unsuitable, and they harm the seagrass beds.”

Romero Llovet hopes that now with the new three cadets recently graduated from the DRNA ranger academy, they can begin to intervene. But he needs, in his opinion, two more rangers to cover the needs. The eternal crisis, according to the mayor executive, is the DRNA’s legal division. The rangers can file all complaints, but the bureaucratic process “is very slow.”

“I have always thought that the DNA’s legal division should be eliminated. They intervene, years go by, and the cases are not heard,” he said. “I worked at DRNA, and I had to work shifts alone [as a ranger]. Now there must be two or three [rangers] on a boat. I rode alone and intervened alone. I went into the canal, moved boats alone, and gave out tickets alone. And the DRNA’s legal division was almost always an obstacle,” he pointed out.

The CPI requested a reaction from the DRNA and got no response.

Fishing in the Luis Peña Reserve

Lourdes Feliciano Morales is the chairwoman of the Luis Peña Canal Board, the first “no-fishing” marine protected area designated in the waters of Puerto Rico, in 1999. She assures that “the problem in Culebra is enormous,” referring to the pile-up of situations that condition the quality of life there.

“They are fishing in the reserve for species that are banned,” says the community leader. “Some of those people aren’t even local fishermen.” She refers to the tentacles of tourism and business demand, a phenomenon that isn’t on par with the realities of the Island Municipality, where there are hardly any shops that satisfy the offer of the restaurants. They fish indiscriminately for kingfish, lobster, and grouper, among other species. The lack of supervision in the waters of Culebra complicates the mission of reporting illegalities. “The local fisherman is seeing how they destroy what cost so much to defend,” she says.

Feliciano Morales believes the issue of the buoys also extends to the demarcation of speed limits in the Ensenada Honda Canal. In her 65 years, the community leader has never seen as many manatees as she sees these days. “We lost one yesterday. We need the buoys so that they at least respect that area a little. They sail at excessive speed in the bay. If we don’t have enough rangers, we should at least have the police in the waters of Culebra. Something must be done, because what’s the point of having dedicated ourselves for so many decades to defending and protecting our resources?”