PUNTA CANA, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC — “My business was here,” said Julio Rodríguez, standing in the sand. Right where he stood, there used to be an structure made out of wood, from which excursion packages were offered to tourists since the 1990s.

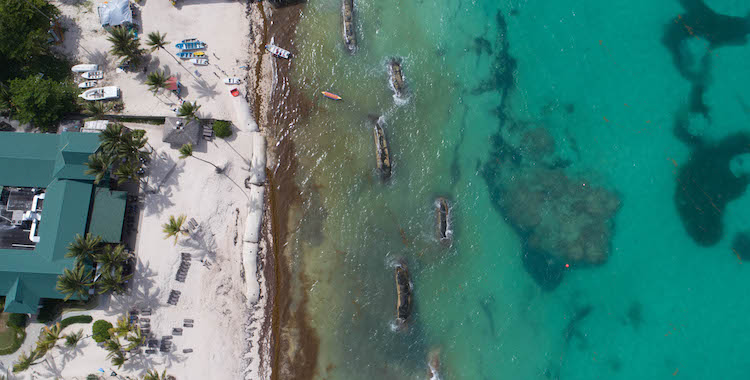

In 2006, he looked at the turquoise water of the Arena Gorda beach, some 25 meters away from his post. He enjoyed watching foreigners walk by his artisan shop. A few years ago, he realized that the sea was approaching progressively, until the waves hit the pillars of his structure and it ceded. At age 60, he watched worriedly how the other 63 establishments in the area faced the same threat.

That morning in the summer of 2017, Julio said he has heard different explanations of why the sea penetrated more than 20 meters to that point on the beach. He cited global warming and the destruction of corals. “Nature and oneself,” he added. “You know that one contributes; people who have no knowledge of the damage done to this often cause harm, consciously or unconsciously.”

In this way, Julio summarized what happens on the coasts of Punta Cana, a world-renowned tourist destination in the Dominican Republic that has increased by more than 21,000 the number of hotel rooms since 2001, but that is losing meters of beach due to an erosive process attributed to climate change and construction without respect for the environment.

This represents a threat to the tourism industry, which is a pillar of the country’s economy, defined by the Minister of Tourism, Francisco Javier García, as “the goose that lays the golden eggs.” The hotel, bar and restaurant sector represented 7.9% of the Dominican gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017.

The land of Punta Cana included dunes, mangrove swamps and wetlands that were filled or dredged to build hotel complexes and other structures. Although this activity is regulated and constructions were in violation of the 60 meter-wide maritime-terrestrial zone, whereby construction is prohibited with some exceptions authorized by law and decrees—, the Ministry of the Environment has not registered in its archives any sanctions related to Punta Cana since 2009.

Punta Cana is located in La Altagracia, a province with more than 330,300 residents on the east coast of the island. It is one of the most visited tourist places in the Caribbean. Its attractions include beaches and communities such as Uvero Alto, Bávaro, Cortecito, Cabeza de Toro, Arena Gorda and Punta Cana.

The province is often criticized from a climate change perspective as it has the largest percentage of underground aquifers affected by salinization linked to marine intrusion and beaches suffering from erosion. This was established in a 2012 study conducted by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), The Nature Conservancy and the Dominican Institute for Integral Development (IDDI).

When the development of tourism projects in remote and highly forested Punta Cana began in the 1970s, the hospitality industry burst into the scene. It already represents 23.3% of employment in La Altagracia, according to the study “Dominican Tourism, A Sea of Opportunities,” published in 2017 by the National Association of Hotels & Tourism (Asonahores by its Spanish acronym).

Development began with a small hotel known as Punta Cana Club, with capacity for 40 people and led by Frank Rainieri, a Dominican, and Theodore Kheel, an American. The expansion continued in the area and investors, mostly Spaniards, attracted by the pristine beaches, expanded to Bávaro, north of Punta Cana, with “all inclusive” hotel projects, including a 400-room complex managed by the Barceló chain.

Taking advantage of the enormous width of the beaches, hotels began to be built as close as possible to the turquoise sea in which the warm Caribbean sun reflects. This caused the area’s dunes to disappear under many buildings, structures and roads, says Nina Lysenko, Conservation and Coastal & Marine Resources Management director at the Ministry of the Environment.

Also affected were the mangrove swamps, an ecosystem that acts as a natural barrier or wall against the strong winds and waves produced by hurricanes or tsunamis. It plays a vital role in the protection of coasts against erosion caused by wind or waves.

The rapid growth of the industry brought about informal infrastructure, real estate projects and private businesses. By 2017, Punta Cana had more than 85 tourist accommodation sites that exceeded 39,500 rooms, which comprised 51% of hotel rooms in the country, according to Asonahores data. The projection is that the number will increase by the end of 2018, due to the construction of more projects.

Only in 2017, this destination, which mostly offers coastal tourism, had an average occupancy rate of 82.8%. It is a key pillar for the Dominican tourism industry, which on a general level, generates more than $7 billion in revenues annually, the Dominican Central Bank estimated.

The local tourism sector, moreover, registered an accumulated direct foreign investment (FDI), of $1.827 billion from 2013 to the third quarter of 2016, or 22% of total FDI in that period, says the Asonahores study.

Punta Cana also houses an airport with the same name, which due to its high passenger traffic, is the most dynamic in the country. It was the point of entry for 67.6% of tourists in 2017, or 3,620,711 nonresident foreigners, mostly from North America and Europe, according to figures from the Central Bank.

The Arrival of Extreme Irma and María

The Caribbean suffered severe atmospheric events in 2017, being a region that is on high alert six months every year during the Atlantic hurricane season. The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) described this past season as “extremely active” and “the most devastating so far in the 21st century.”

As part of that high activity, on Sept. 7 Hurricane Irma passed 95 kilometers off the northeast coast of the country, as a category 4 storm with winds of up to 280 kilometers per hour. Six days later, researchers from Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD) traveled to the tourist area. They sought to verify if the phenomenon had varied measurements made in December 2016 across 39 stations in which they study erosion on the Uvero Alto, Macao, Arena Gorda, El Cortecito, Bávaro, Cabeza de Toro, Cabo Engaño, Punta Cana and Juanillo beaches.

They didn’t expect they would have to return that month to do the same thing. On Sept. 21, another hurricane struck: María. The storm approached with category 3, 280 kilometers-per-hour winds, 75 kilometers off the east-northeast coast of the Dominican Republic.

After field and laboratory tests in about three years of research, Gladys Rosado, a biologist, and other academics from UASD and the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), shared in November preliminary results of the project Climate Change and Anthropogenic Activities Impact on the Geomorphology of the Bávaro and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, Beaches.

As a result of Irma and María, an average of 208 meters of beach width (68 with Irma and 140 with María) were lost in Uvero Alto, Macao, Arena Gorda, El Cortecito, Bávaro and Cabeza de Toro, Rosado reported. This figure results from adding up what they measured at different points and comparing it with the records they had before both storms. They also found fish, molluscs and crustaceans, alive and dead, washed ashore by the strong waves.

But Rosado noted that there were “people (from the communities) that were actually happy because the beaches had more sand” and there was no damage in the eastern zone of the island. She asked herself: “How come they got more sand?”

“What happens with the behavior of beaches under hurricane pressure is that it flattens the outline of the beach, and the waves and pressure push down the backend of the beach, while the frontend is eroded; but due to a dynamic mechanism of the ecology of ecosystems, that beach is flattened,” she explained. It’s like an “optical illusion” that hides what happened with the sand.

Rosado went on to warn: “Although these impacts were not of equal magnitude on the entire beachfront, authorities and investors should remain alert for the vulnerability that many of our beaches have to climate change in the region.”

She had photographs showing sand slopes the height of an average person, which hoteliers periodically flatten wherever they can.

According to a census coordinated by researcher Luis Almánzar—who participates in the project with Rosado—there were 308 structures along the coastline and the maritime-terrestrial zone as of December 2016. For the census’ data collection, a hotel and residential complex was considered as a structure.

It shows that 51.6% of the 64.8 kilometers of coastline covered in the census is occupied by structures, mainly in El Cortecito (96.7%) and Punta Cana (92.4%). Both beach areas, along with Uvero Alto, are the ones with the highest percentage of buildings within the 60-meter strip, or maritime-terrestrial zone.

Rafael Méndez Tejeda, an UPR climatologist, explained that data collected by a tide gauge on the island of Magueyes (Puerto Rico) show that from 2000 to 2010, the sea level increased between 7 and 8 millimeters per year. Since 2011, it shot up to between 10 to 12 millimeters annually. This coincides with the increase in the number of cold fronts that pass through the Caribbean, he noted.

Because that area is near to and its conditions are similar to those of the Dominican Republic, the figures are also applicable to the Punta Cana case, Méndez confirmed. “When we talk about 10 millimeters per year, we multiply that by a scale of 1,000; that means it is increasing 1 meter to 1.2 meters horizontally per year,” he calculated.

When asked if there are structures in the census that entered the 60-meter restricted maritime-terrestrial zone due to the rise in sea level, he specified that it doesn’t end with the high water mark. The maritime-terrestrial zone comprises the high water mark into the sand area. He believes that if the structures had been kept outside the 60-meter zone, the impact wouldn’t be so acute.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—which brings together 195 countries—reported that the global mean sea level rose 0.19 meters from 1901 to 2010. IPCC estimates that it will continue to increase due to warmer oceans and the loss of mass in glaciers and ice sheets.

Researchers found active erosion sites in El Cortecito, Arena Gorda, Cabeza de Toro and at the end of Uvero Alto. Rosado noted there are sites with an incidence of physical factors that allow the erosive process to occur, but “if they have structures, it is worse.” She added that “the problem with erosion is made worse.”

Beaches at the Uvero Alto-Juanillo section present morphological changes, such as erosion and accretion (accumulation of sediment), from 1947 to 2012. Causes are attributed to hurricane swells, cold fronts, infrastructure and carrying capacity.

The analysis conducted using information and images since 1947 showed that although the development of infrastructure began at a higher degree during the 1980s, it is after 2000 that the area had an annual increase, and some beaches have already “exhausted their load capacity.” For 2011, it was confirmed that the erosion process increased.

Almánzar explained that the roads or other passages on or through the dunes break the pattern of the vegetation and generate drainage routes toward the beach area, causing loss of sand by runoff.

How did it Come About?

“For the tourism development that took place in the 1990s, the zones that had tourism potential in the country began to develop without having a solid regulation,” recalled Lysenko, from the Ministry of the Environment.

She added: “The General Environmental Act was enacted in 2000. As for environmental protection, there were decrees that mostly dealt with the species individually […], and environmentalists only talked about the species, nobody dealt with territories or coastlines.”

The General Law on the Environment & Natural Resources 64-00 specifies under Article 146 that “the Dominican State will ensure the protection of the spaces that comprise public domain assets in the [60-meter] maritime-terrestrial zone and will guarantee that the aquatic, geological and biological resources, including their flora and fauna, are not subject to destruction, degradation, impairment, disturbance, contamination, inadequate modification, reduction or drainage.”

The government knows about the threats to the environment and this was documented in a study conducted from 2010 to 2012 and commissioned by the Ministry of Tourism to QU4TRE, an environmental consulting company. The study included an “Analysis of classification and proposals for geoenvironmental management of the Dominican Republic beaches.”

Among the main problems of 133 beaches, coves and dunes along the Dominican coasts, the report mentions “lack of planning in the building of structures, fixed and temporary, and in the drying of coastal lagoons for development of tourist infrastructures.” It adds the destruction of dunes and coastal vegetation, and “extraction of aggregates and other materials from the beaches for construction, or extractions of sand on pristine beaches to rebuild degraded beaches.”

“Everything related to beach services and the dune system, such as the location of hammocks, sunshades, volleyball courts, etc., are elements that, without a minimum level of planning and order, can favor erosion processes due to their location and the indiscriminate passage of users to access them,” the study highlights.

In fact, the World Economic Forum’s 2017 Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report ranked the Dominican Republic in the 109th position out of 136 countries evaluated in Enforcement of Environmental Regulations.

The threats

The progressive penetration of the sea that Julio Rodríguez observed in Arena Gorda has affected the beach space of the Ocean Blue & Sand resort. Seeking how to fight against nature, geotubes filled with sand—which at first glance look like beached whales—were placed to hold the force of the waves. It has also been done in other hotels.

Professor Almánzar argues that geotubes generate vertical subsidence due to their weight and produce erosion of the surrounding areas downstream.

On Sept. 8 and 22, 2017, Julio and the other vendors of the Guineo Maduro market in Bávaro made an inventory of what they had to rebuild further away from the water after the damages caused by hurricanes Irma and María. The waves destroyed the businesses’ façades, exposing the eroded sand.

Concrete effects of climate change such as rising sea levels and rains, as well as more intense hurricanes and coastal erosion, are already a reality that is wreaking havoc in the Caribbean, affecting the social and economic life of the islands.

The devastating hurricanes of 2017, Irma and María, exacerbated the problems in the most affected islands, exposing the fragility of their infrastructure and the negligence of governments that didn’t take measures to protect their residents. These events caused more than $175 billion in damages and losses in Puerto Rico, BVI, USVI, Dominica, Antigua & Barbuda and San Marteen. They also sparked the exit of more than 275,000 of its citizens for economic and security reasons.

During Irma, the Dominican government estimated that 75% of hotel rooms in Punta Cana were occupied. For María, 5,000 tourists were evacuated.

In the Dominican Republic, authorities reported that Irma “did not cause any damage to the tourist infrastructure,” while María caused damage only to small bars and restaurants. Both phenomena caused flight cancellations and a reduction in the arrival of tourists of 13.3% (47,701 fewer visitors in September), as well as interrupted sustained growth exhibited by the sector in the first eight months of the year.

Thirteen years ago, the Dominican tourism sector was also threatened. In September 2004, the eastern part of the country was hit by Hurricane Jeanne, a category 1 storm. The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America & the Caribbean (ECLAC) estimated in RD $1,440 million (more than $38.2 million during that time) the direct damages to infrastructure, equipment and tourist facilities in the province of La Altagracia.

The ECLAC report—prepared at the request of the Dominican government—indicated that out of 62 hotels, at least 18 (some of these with more than 500 rooms) temporarily closed. “The damages were caused by floods caused by the decreased storage capacity of the Bávaro Lagoon and the mangrove swamp,” the entity said in its report.

It added: “The movement of the waters of the Bávaro Lagoon-Mangrove system toward the natural drainage points was affected by various constructions linked to hotel developments in the area such as roads, fences and buildings within the mangrove area.”

The Bávaro and Mala Punta lagoons are interconnected by a narrow strip of wetlands extending some 15 kilometers to Macao. This lagoon system corresponds to a land depression where runoff from rainfall is captured.

Hoteliers: Excuses and defenses

“The development has sometimes generated abuses and other uses,” conceded Ernesto Veloz, a businessman and president of the East Zone Hotels & Touristic Projects Association (Asoleste by its Spanish acronym).

He also assured that hotels were located respecting the wetlands and that when tourism development began in the area, two hotel projects, from the Barceló and Meliá chains, were designed to “coexist with the mangroves.”

Veloz admitted that land had to be filled in some projects, while in others, a sewer system was installed to allow the flow of water. But he also justified these actions stating that the hotel chains arrived when there was no regulation.

He argued, moreover, that “the few” that have respected the environment are the hotel complexes, because when they are built, they must have an aqueduct and a wastewater treatment plant. “Informal development is one that does not have [these] services,” Veloz said.

The Ministry of the Environment was asked to provide a report on sanctions issued for violation of the 60-meter-wide maritime-terrestrial zone and filling of mangroves in the vicinity of Punta Cana. It responded via email: “After an exhaustive search in our database, we did not find any sanction imposed under that concept in that area. It should be noted that although the strip is public property in accordance with Article 2 of Act No. 305-68 of May 23, 1968, all types of construction are prohibited, except for those that are authorized by the Executive Branch for tourist activities and others that apply, of public utility.”

Authorizations to build in the 60-meter zone are granted by a decree of the Executive Branch, which has warned that the permit will be conditioned “to the beneficiary making rational use of the coastline and to the previous fulfillment of the applicable provisions […] relating to the construction of tourist infrastructure and the preservation of the environment and natural resources.”

Thus, for example, pursuant to the decree 455-02, former President Hipólito Mejía authorized Cap Cana, SA, in the province of La Altagracia to build in the 60-meter maritime-terrestrial zone a sports marina with berths for yachts, mini cruises and other types of boats. Under decree 644-07, former President Leonel Fernández allowed Paraíso Tropical, S.A., to develop the Beach Club of the Punta Perla Caribbean Golf Marina & Spa Resort. In addition, Fernández, through decree 396-12, authorized the development of the Costa Atlántica Beach Apartments tourist project, also in the maritime-terrestrial zone.

Since Dec. 15, 1986, the government has emphasized tourism in the east, establishing as a priority demarcation the Macao/Punta Cana Tourist Zone and the city of Higüey, La Altagracia, as the locality of support for tourist services in the area. It tasked the Ministry of Tourism with the enforcement of planning regulations, and ordered that the demarcation be subject to construction control and zoning regulations.

Years later, the Ministry of Tourism issued a resolution that establishes that land areas defined as “wetlands” should be free of any occupation and be organized within an environmental management plan.

Something similar was ratified under resolution 7-2012 of April 26, 2012, which establishes a Punta Cana, Bávaro-Macao Sector Plan for Territorial Tourism Planning. It indicates that every project, urbanization or tourist complex must comply with the laws, decrees and rules that protect the coastal and mangrove ecosystems, and the wetland areas will be free of occupation and incorporated into the attractions of the project.

Despite the regulations and the responsibility given to the Ministry of Tourism, the tourist zone and adjacent communities have yet to be straightened up. The government institution acknowledged in writing for this investigation that the area’s “original development was not based on a land use plan, so that the appropriation of land, especially in the informal sector, has occurred spontaneously.”

It added that the area has a land-use plan of a regulatory nature, yet the town requires comprehensive reform projects that allow a better definition of service and residential areas, and clean up and integrate the urban fabric with degraded areas.

When Diario Libre/Center for Investigative Journalism tried to verify if the hotels built in Punta Cana have the required permits in the Ministry of Public Works, the agency responded that Act 200-04 on Free Access to Public Information limits the obligation to inform “when it comes to commercial, industrial, scientific or technical secrets, property of private individuals or of the State, or industrial and commercial confidential information or reserved from third parties that the administration has received due to a process or procurement to obtain a permit, authorization or any other procedure and has been delivered for that sole purpose, whose disclosure may cause economic damage.”

When asked what measures were taken so that the modification of ecosystems such as mangroves and wetlands didn’t cause an environmental impact, the Ministry of Tourism responded in writing that the environmental impact studies of the projects are regulated by the Ministry of the Environment, which grants an environmental license to issue the “No Objection” determination of land use granted by Tourism.

The list of hotels registered by Asonahores in Punta Cana was provided to the Ministry of the Environment in 2016 to verify if they have environmental permits. Unlike the Ministry of Public Works, the agency did respond. It reported that only 60% of the hotels on the list are authorized; the rest didn’t appear in its database or their names resembled that of other projects that have permits.

On Oct. 12, 2017, the Ministry of Tourism modified the Tourism Territorial Ordinance Plan for Punta Cana, Bávaro-Macao through a resolution announced in December. It increased from four and five to 22 the permitted levels in the constructions in the Macao Environmental Unit, a variation that Asonahores has demanded to be reconsidered because it introduces a radical change in the Punta Cana development model based on low density and low height, and because the Ordinance Plan was intended for 10 years.

Tourism argued that it is imperative to update building parameters due to the continuous urban growth and discouraged to continue with a horizontal expansion model. There is also the threats and damages caused by climate change and the importance of preserving the lagoons, the coastline and the mangrove areas that include areas with tourism potential in which development has not been possible to date because its protection is regulated. The agency understands that one way to do this is by introducing a building code in which less land is occupied and incorporates mangroves as an attraction of the project.

Hoteliers have denounced that the change favors investors and that the construction of two projects has already been authorized in the Macao beach.

“They are obviously generating benefits for one sector by harming another,” Veloz said. “We, in the hotel areas, have been very zealous to respect the environment and respect what has made us successful, which is low height and low density.”

In Cap Cana, a real estate and hotel complex, the construction of 17 towers is on the pipeline, fiscal incentives for these projects were approved on Dec. 19, 15 of which are linked to the company Cap Cana, S.A. and other investors.

The company has relations with The Trump Organization, which together in 2007 unsuccessfully launched Trump Farallón Estates at the Cap Cana project, which included villas, a golf course, a condo-hotel and a beach club.

In February 2017, Cap Cana executives received Eric Trump, the son of the U.S. President Donald Trump and who observed the real estate development of Cap Cana. That year, Tourism modified the density of buildings in the area, which would benefit the company and other developments of its kind.

Francisco Domínguez Brito, minister of the Environment, confirmed that environmental permits have been requested for the aforementioned towers and are in process; they would rise more than a kilometer from the beach. This was also confirmed by Cap Cana, S.A., in advertising spaces in January 2018 in the national press in which it said: “Hotels are usually built on the first lines of beaches, and in some cases, the second and third lines of land are left to the mercy of the suburbs. The only way to revalue these lands would be with real estate and hotel products that, prevented from offering access to a beach, can offer a view of the sea.”

Asoleste notified on Dec. 20, 2017, a formal opposition before the Department of Urban Planning and the City Council of Higüey to grant permits and certifications to projects higher than five levels in the municipal tourist district of Verón-Punta Cana.

After meeting with the minister of Tourism, Asonahores announced in early January the withdrawal of an appeal for reconsideration of the resolution that had been submitted to the agency, to open a process of dialogue with the government. There was a meeting on March 22, but no satisfactory agreement was reached. Several sources assured that the hoteliers defend their interest of development as it is, of low density.

Is the environmental situation remediable?

Biologist Rosado believes that beaches should be left alone in their space because they can recover with their own natural dynamics. However, the Dominican government planned a solution that includes the investment of $64.6 million to regenerate the beaches that are degraded.

In September 2016, the Ministry of Tourism called for an international public bidding for the execution of a beach regeneration project that was won by Acciona IDC Regeneración de Playas, a consortium that comprises the Spanish company Acciona Infraestructuras and the Dominican company Inversiones y Construcciones del Caribe. The plan includes intervention in nine beach systems along the coast of the country, including Cabeza de Toro, Macao and Arena Gorda-El Cortecito.

One of the actions will be the dumping of sand on the beaches that have lost it. “The sandbanks for extraction in the cases where it is needed are located in nearby areas,” the Ministry of Tourism stated. “The sand to be used in each beach is sand that was originally on the same beaches that will be intervened. No sand will be brought from other coastal systems and no growth of beach areas will be contemplated, but only those beaches that have suffered severe erosion will be regenerated.”

The project has yet to kick off, although the Tourism minister and Javier Miguélez Fernández, a representative of Acciona IDC Regeneración de Playas, signed the execution contract on Dec. 20, 2016, for $64,649,793.13.

The State General Budget of 2018 includes authorizing the Executive Branch, through the Ministry of Finance, to contract the Beach Regeneration Project, for a maximum amount of $70 million, plus the insurance premium against risks, if applicable, to be arranged with international banks.

For its part, the Puntacana Group Foundation and other entities are working on a project to recover the coral reef.

Corals help prevent erosion and decrease the force of the waves, while serving as protection against the effects of storms and hurricanes. But in five places analyzed in the study “The status of coral reefs in the Dominican Republic,” it was found that the Punta Cana reef has the lowest coverage (2.8%) of live corals and the most abundant of macroalgae, which can harm their reproductive performance. This is attributed to global warming, overfishing and habitat modification, according to the study published in 2015 by Rubén Torres, of Reef Check Dominican Republic, and Robert Steneck, of the University of Maine.

“We have more than six kilometers of tissue transplanted from reefs, that is, it grew in nurseries and was planted in the reef. It has been sown from the north of our property to the front of Cap Cana; we have more than 60 transplant sites,” explained Jake Kheel, vice president of the Puntacana Group Foundation.

Hoteliers also claim they have spent up to $100,000 on sargassum retention barriers that cover only one kilometer. Sargassum is a brown algae that temporarily float to the coast in piles and look like a spot in the white sand. It gives off a strong smell, similar to that of sulfur, where it accumulates.

They also spend on mechanical shovels that collect countless amounts of sargassum that are deposited in the vicinity of the hotels until it rots since they have not found yet what to do with it. Sand is also added to the collection process, adding to the loss caused by erosion. There are no penalties for it.

The company AlgaeNova develops an experimental project with a barge that picks up the sargassum in the water. It plans to recycle it to make biodegradable materials such as dishes and other containers.

Photo by Marvin del Cid | Diario Libre

A machine picks up the accumulated sargassum, on August 31, 2017, on a beach in Bávaro.

A German tourist was walking at the Cabeza de Toro beach in Punta Cana on a September morning in 2017. She avoided stepping on the accumulated sargassum. She had arrived for the first time to the country the previous day and in the photos she saw before traveling, there was no such algae. She was disappointed, but she knew about the issue and that researchers attribute their massive arrival to climate change. “I think we’re all responsible for the climate. Everything changes, even in Germany we have changes in climate,” she said.

Days later, the waves generated by Hurricane Irma brought tons of sargassum to the coast; Hurricane María did the opposite: it withdrew it.

Scientists suggest that the influx of sargassum in the Caribbean is due to an increase in water temperatures and low winds, which affect ocean currents.

The “Opinion, Attitude and Motivation Survey to Nonresident Foreigners,” conducted by the Central Bank, found that 29.7% of 11,186 tourists who visited the country in 2016 did so because of the quality of its beaches and 17.9% because of the weather.

The Ministry of Tourism has received complaints about the state of some beaches, the agency confirmed, but it could not specify which related reports have been made or if sanctions have been issued.

Out of 183 countries, the Dominican Republic was—on average—the tenth most affected by extreme weather events between 1992-2011, according to the 2013 Global Climate Risk Index prepared by Germanwatch, a German nongovernmental organization. It calculated the occurrence of 49 events during that period in the nation and 2.47 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants.

The government seeks to increase the number of tourists visiting the country to 10 million by 2022. As of December 2017, it was estimated that 6,187,542 nonresident travelers arrived by air in that year, of which 87% were foreigners, while the rest were Dominicans.

Last September, President Danilo Medina warned at the United Nations that with every hurricane that hits the country, the sand on the coasts decreases. “There is the possibility, even, that one of these megacyclones such as Irma completely erodes the beaches of some tourist areas,” he said.

Updated analisis to 2018 by the Geophysical Fluids Dynamics Laboratory of NOAA suggest that although it is not yet possible to say if more or less hurricanes will occur in the future due to global warming, it is expected that those which arrive near the end of the 21st century will be stronger and have significantly more intense rainfall than in current climate conditions.

Despite the scenario, the Chamber of Deputies has yet to approve the Climate Change in the Dominican Republic bill, which would mandate taking measures so that the construction of infrastructure takes into account the variability and climate change. The legislation was proposed for the first time in 2014 by then lawmaker Guadalupe Valdez and Deputy Ricardo Contreras. It was placed on the list of priority initiatives in 2017, sent to a commission for study, but it expired. Contreras and deputy Marcos Cross reintroduced it in March of this year. Valdez considers there has been no political interest to approve it.

“It expired because Congress always has many bills and sometimes they don’t give them adequate follow-up,” said Ernesto Reyna, executive vice president of the government’s National Council for Climate Change and the Clean Development Mechanism. “But this time we hope that it doesn’t expire because we have been in conversation with the Chamber of Deputies’ Environment Commission and with the Senate, and they really are very interested.”

A request for the minutes of the meetings of the Commission was made to the Chamber of Deputies to inquire about the opponents or entities that have lobbied against the legislative initiative. The Office of Access to Information responded that they weren’t available because the bill was in the analysis and deliberation phase.

This story is part of the ISLANDS ADRIFT series, resulting of the work of a dozen Caribbean journalists led by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI) in Puerto Rico. The investigations were possible in part with the support of Ford Foundation, Para la Naturaleza, Miranda Foundation, Angel Ramos Foundation and Open Society Foundations.

Próximo en la serie

7 / 7

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.