When Hurricane Fiona caused a general blackout on September 18, the government of Puerto Rico trusted that terminals and wholesalers Buckeye, Peerless and Total would be ready to supply diesel during the emergency. But after the winds subsided, while the blackout continued, fuel-hauling trucks lined up at the Buckeye facility in Yabucoa, in the southeast coast, waiting.

The company’s emergency generator did not have the capacity to energize the distribution facilities. In Peñuelas, in the southern coast, while the government said that there were enough supplies, Peerless had to start rationing diesel four days after the hurricane, to face the increase in demand.

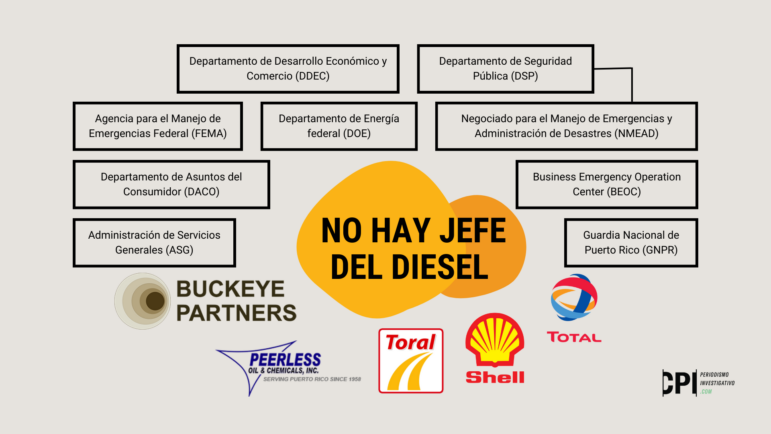

Neither the Bureau for Emergency and Disaster Management (NMEAD, in Spanish) nor the Department of Economic Development and Commerce (DDEC, in Spanish) made sure before Fiona that the terminals and wholesalers had enough gasoline and diesel supplies needed in that emergency. Buckeye’s lack of preparedness affected the fuel supply chain needed by most of the public and private generators that temporarily power the island after disasters, the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) found.

Luis Vázquez, general manager of Peerless, claimed that his company was prepared but had to ration because new customers who had run out of fuel, such as wholesalers Total and Shell (Toral), and began to arrive at its Peñuelas terminal at a time when it needed to secure supplies for its public sector customers, the Maritime Transportation Authority (ATM, in Spanish), the US Navy, and 10 municipalities.

“If I said that I was going to leave the refill facility open, we would have run out of diesel in one day. The demand was brutal,” Vázquez said. “What has to happen is that, before the hurricane season, government agencies, through the COE [Emergency Operations Center], hold a meeting and call” the fuel suppliers to report on hurricane preparedness. Vázquez assured that, after Hurricane María in 2017, the only government meeting with wholesale fuel importers occurred after Hurricane Fiona, on November 29, 2022. “We cannot wait for an emergency to happen to provide the information.”

Photo taken from the company’s website.

Puerto Rico faced Fiona, indeed, without an energy assurance plan for disasters in place. Since 2019, the DDEC’s Public Energy Policy Program has been preparing the Energy Assurance Plan, but three years later it has not yet been completed, program Director Carlos Tejera said. The government has requested and received approximately $200,000 in federal funds to create and update these plans. The Energy Transformation and Relief Act of 2014 mandates that the DDEC update this plan each year prior to each hurricane season.

Tejera could not specify a date when he expects the Energy Assurance Plan to be finished. It is missing important parts such as cybersecurity of electrical system communications networks, collecting “resiliency data” and considerations for pandemics that may affect employees in the power generation sector.

The government officials responsible for this plan give different versions of its existence. While Tejera says that it has not been completed, the Secretary of Economic Development, Manuel Cidre, who oversees the Public Energy Policy Program, said it “was updated in 2020 and is constantly being updated.” The CPI then asked the DDEC to deliver that updated document, but the agency said: “the document you are requesting is not yet final, so we cannot share it until it has the final signature.”

The DDEC hired a company, Industrial Security Products, for $95,000 to develop the plan, through a contract whose validity was extended three times, until December 31, 2021.

Francisco Berríos Portela, who headed the Public Energy Policy Program until he was appointed Undersecretary of the government’s Energy Affairs office in the summer, offers another version: the plan was supposedly completed in 2021 and it was shared with the “corresponding sectors.”

He alleges that in June 2022 exercises were carried out, led by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), with the team that makes up the ESF-12 (a protocol responsible for maintaining electric power during emergencies), together with LUMA (the private company that manages the energy transmission and distribution network), the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), owner of the generation plants, and the Public Energy Policy Program. “The Governor also participated as part of these exercises that were carried out,” Berríos Portela said. Meanwhile, the government is following the 2011 Energy Assurance Plan, developed before Hurricane María. It does not include the fuel preparedness and response elements needed to avoid recurrence of problems, Tejera said.

Diagram by Gabriela A. Carrasquillo Piñeiro | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The federal government recommended an ‘immediate’ plan

The Energy Assurance Plan was developed to be used during emergencies and must include how to address the storage and distribution of fuels that are dispensed to public and private clients. In June 2018, after Hurricane María, the US Department of Energy (DOE) recommended that the government prepare it “immediately” so that the island would be ready for the “next hurricane season,” according to the report Energy Resilience Solutions for the Puerto Rico Grid.

The DOE made its recommendation after Hurricane María destroyed the already weakened electrical grid in 2017, causing one of the longest blackouts in the history of Puerto Rico and the United States, and which left parts of the Island without electricity for up to a year. Fiona also caused a widespread power grid blackout, and it took LUMA up to nearly a month to restore service.

The disruption in distribution logistics was not insignificant. Buckeye and Peerless alone, for example, distribute 70% of the fuel received on the island, according to Puerto Rico Ports Authority Executive Director, Joel A. Pizá, who confirmed the problems the companies faced.

“When they had to transfer fuel from one tank to another, Buckeye’s generator did not have enough capacity, and that caused the dispatch to drop substantially,” explained Pizá. Toral Petroleum has been since early September (before Fiona) the wholesale distributor of the Shell brand and operates in the terminal managed by Buckeye in Yabucoa.

The CPI asked Tejera what his office did to ensure that private terminals and importing wholesalers had diesel. “That’s something that each private entity must address individually,” he said. In a separate interview, NMEAD Interim Director Nino Correa confirmed that nobody makes sure that terminals and wholesalers have fuel available before the hurricanes. “That’s the responsibility of these companies. It isn’t our direct responsibility,” he said.

The NMEAD is responsible for executing the disaster preparedness, response, and recovery plan (Puerto Rico All-Hazard Plan), to which the Energy Assurance Plan must be attached, when it is ready.

Do terminals and wholesalers share emergency plans and information about supply levels with your agency? the CPI asked. “Not so far,” Correa said. Tejera and Correa’s responses confirm that there is no government entity that coordinates with private companies to ensure strategic fuel supplies before hurricanes that recurrently cause long blackouts. That coordination is crucial for an island like Puerto Rico, the jurisdiction most affected by disasters during the last 20 years according to the Global Climate Risk Index.

‘They didn’t learn anything from Hurricane María’

In visits to mountain region towns, the CPI validated immediately after Fiona the lack of fuel at gas stations. For a few days, Puerto Ricans saw scenes like those caused by Hurricane María five years earlier.

Private hospitals such as the Metro Pavía Health System network, the Hospital San Lucas in Ponce and the Adjuntas Diagnostic and Treatment Center (CDT, in Spanish) began to have problems getting diesel after Fiona. Those medical facilities are responsible for having their own emergency generators and contracting with private fuel distributors. If something goes wrong, they go to the NMEAD Emergency Operations Center (COE) and ask for help.

“Preventively, there’s no preparedness, no government entity that ensures diesel for hospitals before a hurricane,” said Jaime Plá, executive president of the Puerto Rico Hospitals Association. “The National Guard must be activated a couple of days before the event, to see which sites are going to need diesel for medical reasons. The National Guard was deployed late, like four or five days after Fiona. It supplied some private hospitals,” he added.

Photos by Sgt. Alexis Velez | Puerto Rico National Guard

Without an energy assurance plan for disasters, and without oversight for the fuel terminals, part of Puerto Rico’s response to hurricanes is at the mercy of the preparation that private companies decide to undertake. The greatest risk lies with Buckeye, which has one of the largest multi-fuel supplies in Puerto Rico (172 million gallons combined).

The company was established in Puerto Rico in 2001 as a subsidiary of Buckeye Partners, based in Houston, Texas. It is in Yabucoa, in the southeast coast of the island, where hurricanes commonly make landfall, making it a high-risk location. Peerless, meanwhile, has a storage capacity of 67 million gallons of multiple fuels, and owns the Ecomaxx gas stations. It has just been acquired by Sunoco, one of the largest fuel distribution companies in the US.

After the problems in Yabucoa, the Puerto Rico Aqueduct and Sewer Authority’s (PRASA) main diesel supplier, Mega Fuel, began having difficulties refueling at the Buckeye terminal and delivering it to the public corporation, said Orlando Rodríguez, PRASA’s deputy director of infrastructure. The government, through the General Services Administration, had to look for alternatives so that essential agencies and corporations, such as PRASA, had diesel available during the emergency. The Department of Transportation and Public Works and PREPA shared a portion of their limited supplies with PRASA, Rodríguez said.

“Mega Fuel was supplied from that port and that’s why the General Services Administration, quickly looked for the alternative of signing a contract with Total to have diesel available,” Rodríguez explained. Mega Fuel, Buckeye, Total and Toral did not respond to interview requests from the CPI.

PRASA also asked the Puerto Rico House of Representatives for help to get diesel, said Rep. Ángel Fourquet, one of the proponents of Joint House Resolution 389. The legislative measure seeks to declare “a state of emergency in the absence of a proper distribution structure of fuel and derivatives in Puerto Rico.”

Since October 17, the legislative measure has been under consideration by the Senate’s Rules and Calendar Committee. Its chairman, Sen. Javier Aponte Dalmau, said it will be addressed at the beginning of the next legislative session in January. JHR 389 seeks that DACO requires wholesalers to establish, in all diesel distribution points, preference to deliver to PRASA facilities, institutions that provide health services, elderly homes and industries that produce drugs or medical equipment, among others.

“There was no effective communication between the agencies and essential services corporations… A plan is a theory that they couldn’t put into practice,” Fourquet told the CPI. “We saw that they didn’t learn anything from Hurricane María,” he said, referring to the government’s lack of readiness.

A senseless diesel cargo ship

The government’s official version, in the words of Edan Rivera, former Secretary of Puerto Rico Department of Consumer Affairs (DACO, in Spanish), was that there was a fuel distribution problem, not supplies. This version contradicts the fact that the government of Puerto Rico had to request a waiver for the GH Parks barge, bearing the Marshall Islands flag, to deliver fuel to the Peerless dock.

Because it was not a ship bearing a US-flag, it was prevented from anchoring in Puerto Rico by the Jones Act, which prohibits a foreign ship from moving between two US ports and their territories. The US Secretary of Homeland Security, Alejandro Mayorkas, granted a waiver to the local government on September 28, so that “the people of Puerto Rico have sufficient diesel to run generators needed for electricity and the functioning of critical facilities as they recover from Hurricane Fiona.”

When the waiver was granted to the GH Parks barge, the Puerto Rico Manufacturers Association began to suspect that there truly were problems with supplies. The entity, in effect, received calls from “many” of its members who needed diesel, Yandia Pérez, executive vice president of that trade group, said.

Vázquez, the executive from Peerless, petitioned the barge given the high demand for diesel after Fiona, because his regular supplier was scheduled to deliver fuel, but in October. He recalled that Puerto Rico competes for fuel in an international market disrupted by the war in Ukraine. Distributors now prefer to take the fuel to Europe, where they get better prices.

The Puerto Rico Manufacturers Association knows, that regardless of those shipments, the demand for diesel increases after hurricanes. “There was probably more demand than after María because more people have generators now. Small and medium-sized businesses were better prepared with larger generators, for example, not to turn on a refrigerator but an entire restaurant,” Pérez said.

“In an island-wide emergency plan, you should know how many gallons of diesel there are available,” she claimed. Without emergency fuel, the effect on small and medium-sized businesses is that they may have to shut down operations. “There was a high risk of affecting industries,” Pérez added.

In a private meeting with Berríos Portela and Tejera on November 3rd, the Puerto Rico Manufacturers Association asked them for better plans to serve the industrial sector during emergencies, including securing diesel supplies, Pérez said.

FEMA recommended better fuel supply preparedness ahead of Fiona

After Hurricane María, Ann Campbell, a professor from the Department of Business Analytics at the University of Iowa, analyzed Puerto Rico’s supply problems. The academic prepared, along with two experts in transportation logistics, a study on the need for Puerto Rico to take special energy security measures to avoid repeating the same problems of the great hurricane of 2017.

At that time, Puerto Rico proved that islands are more vulnerable to natural disasters than continents. Unlike some countries or continental states, where an affected area can receive by land diesel trucks from another neighboring town, Puerto Rico must wait for everything to arrive by ships. The refined fuels that are burned in Puerto Rico are imported, showing the island’s high dependency for its energy survival. They further noted the high dependence on fossil fuel that contributes to the carbon emissions that cause global warming.

In June 2021, Campbell shared some alternatives with FEMA, such as the need for Puerto Rico to have an additional fuel reserve ahead of the hurricanes, in addition to that of wholesale importers; keep vessels ready to come to the island with diesel immediately after a disaster; and store it in strategic locations at different points, away from risky places like the southeast.

The academics “suggest to us that, instead of having the reserves in the same place, you have to diversify the areas,” said Marie González, head of the FEMA Planning Branch, which establishes the guidelines for the preparation of the government of Puerto Rico’s disaster plan.

In November 2021, FEMA shared the observations from the study with the NMEAD and DDEC, noting that they needed to make some preparedness changes to protect supplies and distribution. “We offer them technical assistance. We can’t demand action from any state government,” she said.

Correa and Alexis Torres, secretary of the Department of Public Safety, insisted that before Fiona they held more than 10 meetings to go over the preparation and response to hurricanes, including ensuring fuel supplies, under the All-Hazard catastrophe plan.

The problem is that the plan is incomplete because it does not have an energy assurance component, and it does not identify an official or agency in charge of coordinating and establishing priorities for the diesel industry. Correa and Torres did speak during the interview with the CPI of the responsibility of the DDEC in “activating the private sector,” but not that this agency should finish and follow the Energy Assurance Plan.

Part of the emergency preparedness and response is carried out with the Business Emergency Operation Center (BEOC), a nonprofit organization that serves the government as a consultant of the private sector. The director of the BEOC, Emilio Colón Zavala, stressed that his organization doesn’t have the force of law to coordinate the fuel safety strategy. He summarized the solution clearly: “Is there a need for a more robust emergency plan for the diesel supply chain? Yes, of course.”

Reporter Vanessa Colón Almenas contributed to this story.

Comments to [email protected]

Próximo en la serie

2 / 8

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.