In the Bajura neighborhood, in Isabela, a flood-prone area, with a high risk of erosion, classified as Specially Protected Rustic Land adjacent to the Northern Karst region and the maritime-terrestrial zone, there is a proposal for the Isabela Reefs project, which includes 33 tourist residential units, a clubhouse with swimming pool, games area and restaurant.

The land where investment fund advisor Daniel Grunberg Walg and investor Tyson Carter propose to build the project is in front of Shacks Beach, where there are dunes. In comments sent to the Puerto Rico Permit Management Office (OGPe, in Spanish) on April 12, 2023, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA, in Spanish) warned that the construction of Isabela Reefs could reverse the dune restoration work being done in this area.

“Any filling in this area to eliminate the land’s flood-prone condition [as part of the construction] is not consistent with the restoration and reforestation efforts of the dunes done on the property,” the document says.

Residents of the Quique Bravo community, in Bajura, where Shacks Beach is located, oppose the project because they remember very well that when Hurricane María hit Puerto Rico, on September 20, 2017, the only road to access the sector was flooded after waves surged into the mouth of the Los Cedros stream, whose level had increased due to the impetuous rains. Residents were isolated for more than three days, and water flooded their homes and businesses.

Courtesy photo

Elaine Cosby, who lived in the Quique Bravo neighborhood at the time, recalled that the water was more than three and a half feet high, getting into part of her property and a bar that she owned at the time. She has since moved out of there.

The residents of the neighborhood, in which there are about 60 homes, fear that the construction of the residential project will aggravate the flooding due to storm surges that the community is already experiencing after having lost a large part of their dunes due to sand extraction that happened on the Isabela coastline, in the North, for decades.

In May 2022, the Department of Agriculture (DA) objected to the project. The agency stated that the land had and could have agricultural use, and that “the magnitude of the proposed project would alter the land use pattern of the area.” However, in January 2023, the agency, still headed by Ramón González Beiró, radically changed its stance and endorsed the development.

“Upon review and evaluation of this application again, it was determined that these lands are classified as developable,” the DA said. “Agricultural activity will not be affected by this project,” it concluded.

The letter showing the change in stance was sent by the OGPe at the request of the CPI, after the agency’s press officer, Lisdián Acevedo, reiterated three times that the Department of Agriculture had maintained its objection to the project. Acevedo is also the press officer responsible for Governor Pedro Pierluisi’s re-election campaign.

In 2018, a year after Hurricane María, Isabela was among the municipalities having several sections of coastlines experiencing the most erosion, according to the draft plan of the Committee of Experts and Advisors on Climate Change (CEACC).

According to the study of the state of the beaches led by Maritza Barreto Orta, Isabela is also one of the municipalities in which the coastline had the greatest migration inland, with approximately 3.5 kilometers, specifically on beaches like Shacks.

“The implication of the movement of the water line inland is the increased exposure of the coastal zone to flooding in case of new events,” the document says.

Government ignores recommendations from communities and experts to face the climate crisis

While, on the one hand, the government of Puerto Rico orders and allocates funds to mitigate coastal erosion and delegates to the CEACC the creation of a plan that contributes to reducing the vulnerability of the population and ecosystems to climate change, laxity in the granting of permits, and lack of supervision of activities on the coast undermine protection and restoration initiatives, the CPI found during its investigation. Two of the proposed construction projects in the coastal area identified for this investigation have as common denominator investors who are Act 22 (now “Act 60”) beneficiaries. This incentive exempts foreigners, who move their main residence to Puerto Rico, from paying capital gains taxes.

In April 2023, the governor of Puerto Rico signed an executive order declaring an Emergency Declaration for Coastal Erosion but did not include a moratorium on construction in the coastal area, as the Committee of Experts and Advisors on Climate Change recommended in 2021.

“Regulatory agencies have taken no action to make communities more resilient, especially [when they have been] allowing and approving permits to continue developing in flood-prone areas and in areas closest to the maritime zone. Areas that were flooded with the impact of María and go on as if nothing had happened, because we don’t learn from our mistakes,” said Ruperto Chaparro Serrano, director of the Sea Grant program at the University of Puerto Rico (UPR).

The floods that occurred on the last weekend of October that caused emergency declarations in San Juan, Guaynabo, and Loíza showed precisely how unprepared Puerto Rico is for extreme atmospheric events that are becoming more frequent due to the climate crisis.

“The damage has already been done. Many of the damages because of climate change are already irreversible,” warned Ernesto Morales, of the National Weather Service, about the impact of climate change at a global level.

After Hurricane María, the government of Puerto Rico announced efforts to restore natural barriers on the coastline. According to figures provided by the DRNA, in the last 10 years, the government allocated nearly $28.4 million in initiatives to protect the coastal resources.

The CEACC, in a document called Courses of Action (COAs), presented several recommendations in 2021 that were intended to be a guide to correct, mitigate, and prevent the effects of climate change in Puerto Rico’s Coastal Zone. Governor Pierluisi accepted 87 of the 103 recommendations.

The Climate Change Mitigation, Adaptation and Resilience Plan prepared by the CEACC lack legal status, so agencies such as the DRNA, the OGPe, and the Planning Board (JP, in Spanish) are not mandated to follow the recommendations made by the committee in 2021, warned Carl Axel Soderberg, member of the CEACC and former director of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The proposed plan is currently open for public comment and a final document is expected to be presented for approval by the Legislative Assembly before the end of the current fiscal year in June 2024.

Puerto Rico’s evolution toward resilience is moving “as slow as molasses” due to government inaction, according to the director of the Sea Grant program. He believes the archipelago is the same or worse than in 2017 in terms of resilience because of government decisions that have increased its vulnerability.

“What the agencies have done all the time is to look the other way,” Chaparro Serrano responded when asked if the government has implemented the recommendations of experts to address the climate crisis.

“When you look at it, what we have are government agencies that aren’t doing their job and the people have to risk being beaten or being taken to court or having an exaggerated bail set, all for the sake of protesting,” the coastal management specialist said.

DRNA Secretary Anaís Rodríguez Vega, said during a forum on climate change and ethics, “The government has financed countless projects around Puerto Rico in collaboration with academia (…) creating more resilient structures, avoiding storm surges so that we have coastal erosion that eliminates the beaches.” Among the agreements, she mentioned a collaboration with the Center for Conservation and Ecological Restoration: Marine Life of the University of Puerto Rico in Aguadilla. After Hurricane María, the university acquired eight contracts with the DRNA amounting to $1,863,200 to restore dunes, among other tasks.

Pedro Saadé Lloréns, a professor at the UPR Law School’s Environmental Clinic in Río Piedras, believes that although there is a draft of the Mitigation, Adaptation, and Resilience Plan to Climate Change and a proposal for a new Coastal Act, the requirements that establish the current laws to grant permits in the coastal zone “aren’t met or are manipulated.”

“Failure to comply with what we have now only aggravates the problem and makes it even more scandalous,” said the environmental law specialist.

Saadé Lloréns said the new threat is the Fiscal Control Board´s (JCF, in Spanish) pressure exerted on the JP as part of the Ease of Doing Business policy “so that it’s allowed to intervene, give an opinion and put pressure on the preparation of the next Joint Regulation.”

Ease of Doing Business is an indicator of how easy it is to do business in Puerto Rico. The JCF uses it in its mission to make it easier to establish and operate a business in Puerto Rico.

“The problems we have with exclusions and abuses under the formula that the Fiscal Control Board is promoting would be worse because it undermines and reduces the environmental and impact analyses to make it faster, so investments come in faster,” Saadé Lloréns warned.

Challenging the demarcation

Despite the opposition of the Quique Bravo community to the Isabela Reefs project, the DRNA secretary signed the demarcation on August 7, 2023, presented by surveyor Javier E. Bidot, hired by the developers. The residential project would be built on one of the few undeveloped lands in that community in the Bajuras neighborhood and which is in a flood-prone area, according to the OGPe and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The community’s lawyer Miguel Sarriera Román anticipated that they would challenge the demarcation, which is the process that determines the limits of those adjacent to the public maritime land domain. The community and several environmental organizations expressed their opposition in March 2023, when the DRNA held a public hearing on the demarcation presented by project proponent Isabela Estates, LLC.

Organizations Amigos del Mar and Salvemos A Playuela supported the claims of the Bajuras community with written testimonies. Héctor Varela Vélez, a member of the Surfrider Foundation, has collaborated with dune restoration in Isabela and supports the claim of the residents. The environmental leader told the CPI that the proposed construction would be on “a giant plain” near Shacks Beach, which would require the elevation of the land by filling, which could cause an increase in water levels due to storm runoff to the detriment of the nearby residents, as has already happened when there is heavy rain.

Community resident Lourdes Irizarry Saua, says the demarcation fails to comply with Regulation 4860, which oversees the maritime-terrestrial zone. She insists that the delimitation should have been further inland, considering the location of some dunes that disappeared due to the abuse of sand extraction during the last century. Irizarry Saua said the demarcation certified by the DRNA allows the private appropriation of public lands.

“Our lives are at risk,” Irizarry Saua warned. “That land floods and collects most of the water when the stream swells and when the sea rises,” she explained.

She said the area not only floods when there are high waves, but that the Los Cedros stream runs through that community and overflows when there are heavy rain events and that many times, the rain, and high waves happen simultaneously. Neighbors fear that the water will have nowhere to go and worsen flooding in the community.

The 32-acre plot of land on which the complex will be developed was purchased for $3.75 million in 2021 by Isabela Estates represented by Daniel Grunberg Walg, according to the purchase deeds. According to the registry of corporations, Isabela Estates has Tyson Carter as a partner and resident agent. Both are beneficiaries of Act 22 of 2012, currently included in Act 60 of 2019.

Grunberg Walg is an expert financial advisor in investment funds with a presence in the United States and Latin America. Between 2019 and 2020, he registered at least seven companies in Puerto Rico. According to a bio published on one of his companies’ websites, he worked at Och-Ziff Capital Management, a hedge fund company that bought junk debt from Puerto Rico in 2014. In 2016, Och-Ziff and its subsidiary OZ Africa Management GP LLC by signing a resolution agreed to pay a $213 million criminal fine to stop the Department of Justice from pursuing criminal prosecution for bribery of officials in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Libya.

The businessman told the CPI that his employment relationship with Och-Ziff ended around 13 years ago and that he was never involved in any of the company’s business or operations in Puerto Rico. He said he neither came to the island as an employee of that company nor was he part of its partnership.

Meanwhile, Carter, who settled on the island in 2017, has registered at least five limited liability companies here, according to the State Department’s registry of corporations. The companies are dedicated to hotel, land, and real estate development.

Carter did not return calls or emails from the CPI.

Natural barrier to waves

The primary dune to the south of the land on which construction is proposed was recently stabilized by Vida Marina of the UPR in Aguadilla. Isabela Estates signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the UPR to restore that dune, said Robert Mayer, director of Marine Life. In November 2022, the proponent also asked the DRNA to “adopt” the beach neighboring its land. The request is still under evaluation, the agency confirmed.

In a telephone interview, the director of Vida Marina acknowledged that an increase in the density of use in the area can affect the stability of the dunes but assured that it is possible to control this impact. He said the dune located in the vicinity of the proposed project could be restored because the project proponent, who owns the land adjacent to the dune, allowed them access to the area, a collaboration that Vida Marina had not reached with the previous owner.

Isabela Estates contributed $68,566 to Vida Marina to cover the restoration and labor, according to an agreement between both parties that was effective between July 25 and September 25, 2022.

Anticipating the possible “public controversy” that the construction of this tourist residential complex would generate, the parties agreed to “collaborate in press releases and other statements” to the media and in any public proceedings needed to describe the scope of the work and its consequences and benefits, the agreement states.

Mayer said previous storm surge flooding in the area was aggravated because the dune had gaps opened by beach visitors, but that those openings were closed off when the new owners bought the property, and people’s access to the beach through there was controlled. He believes the dune’s current stability and the vegetation that covers it is an important barrier to stopping the waves from reaching the community.

The DRNA secretary told the CPI that the certification of the demarcation that Isabela Reefs submitted does not represent an endorsement or approval by the DRNA of the project’s construction. “When a demarcation is done, what is being certified to the owner of the property is how far from its boundaries or limits go,” Rodríguez Vega pointed out.

Michael Scott Collins, who has owned property next to the proposed development for 18 years, would be directly hit. “When the water comes from both sides [of the stream and the sea], it looks like a lagoon,” he described. “When the ocean peeks out after a high tide or storm, you can clearly see the water coming in.”

Although the DRNA signed the demarcation presented by the proponent, the agency expressed its concerns about the project to OGPe in April 2023 “due to the proposed density in a flood-prone area, adjacent to the sea, with high erosion risks, lack of sanitary infrastructure and with SREP (Special Protected Rustic Land) classification.” According to OGPe’s permit management platform, the Single Business Portal (SBP), Isabela Estates is revising the environmental compliance document it submitted to the agency.

Isabela Mayor Miguel Méndez told the CPI he does not know whether he will support the Isabela Reefs project because concerns about flood control have not yet been cleared. In October, the Isabela mayor asked the JP for clarification.

“The issue related to the collection of used water that the project will generate is doubtful,” said the Municipal Executive in the letter in which he expresses concern because developments in the municipality of Aguadilla channel stormwater discharges precisely into the Los Cedros stream.

Neither surveyor Bidot nor Grunberg Walg answered the CPI’s questions about the demarcation. Grunberg Walg said he has met with community residents to discuss their concerns about the work and has had “informational approaches” with the municipality.

The businessman acknowledged that development studies must be as rigorous as possible to avoid any collateral impact on the community. “The law demands that it be so, common sense demands that it be so, it’s our will that it be so,” said Grunberg Walg. “I cannot conceive a design that does not take that reality into consideration.”

More than a decade ago, the DRNA’s Coastal Zone Management Program outlined the Management Plan for the Isabela-Aguadilla Special Planning Area, which proposed delimiting the area, retaking public domain lands in private hands, and protecting easements surveillance, which would include the Quique Bravo sector. However, Marisol Luna Díaz, special assistant to the JP’s president, confirmed to the CPI that it has not been approved.

The Special Planning Areas’ (APE, in Spanish) management plans seek to preserve areas with important coastal natural resources that need special planning to avoid any potential conflict in their socioeconomic uses. The JP and the Governor must approve them. The only APEs that have approved management plans are those of the southwest–La Parguera region, and Piñones and Laguna Tortuguero in the North, the JP confirmed.

Caution in the coral reef area

The Vega Baja and Manatí coastline constitutes one of the richest areas in colonies of maple horn coral in the entire northeastern Caribbean.

In Vega Baja, the VIDAS group has been carrying out an ecological rehabilitation project for 15 years, which includes the planting and mooring of coral fragments. Their monitoring of the ramifications of these corals points to an “excellent” pattern of survival and growth, said the organization’s spokesperson, Ricardo Laureano.

The group also works on data collection and surveillance of stony coral tissue loss disease.

“If the corals weren’t there, the level of penetration from sea to land would have been higher during hurricanes Irma and María and winter storm Riley, because even the fragments modify breaks and reduce wave pressure,” said the reef researcher, who estimated that they have planted more than 20,000 coral fragments in the Vega Baja area.

Photo courtesy of VIDAS

Still, VIDAS’ effort to preserve the reefs is frequently threatened by actions and inactions of the central and municipal governments and the private sector. One of the ongoing threats is used water discharge and rainfall and sanitary runoff leaks near the reef. That’s why they have insisted that a plan be designed to manage these runoffs.

“The Government has to work responsibly to minimize the impact of toxoids [bacterial toxins] that are discharged into bodies of water so that ecological rehabilitation projects are more effective,” said Laureano.

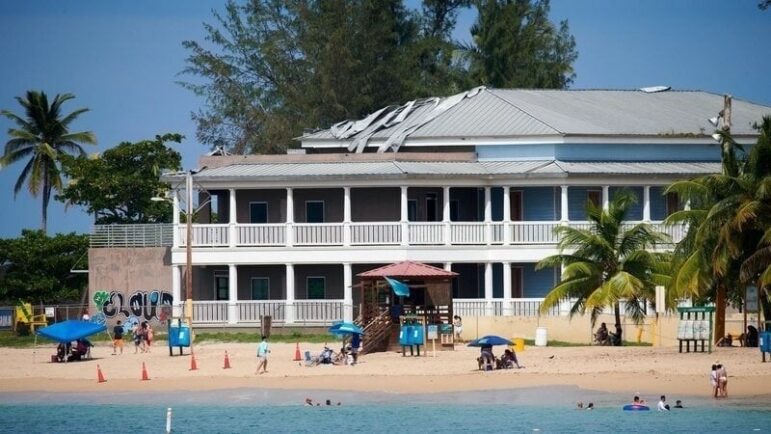

Recently, VIDAS and other sectors of the Vega Baja community warned about the municipality’s proposal to privatize the administration of the La Casona building for tourist purposes. The disused structure faces Puerto Nuevo beach. About 53% of the coast of Vega Baja was subject to erosion in 2018, according to a study of the coasts, especially on the public beach where the controversial facility is located.

Photo by Roberto Rivera Arocho

The municipal administration intended to sign a 30-year lease with an option to buy with Melao Holdings LLC for the development of a 59-room hotel. After citizen mobilization against the transaction due to the possible environmental impact that this use would have, Mayor Marcos Cruz Molina walked away from signing the contract.

Cruz Molina said that the surveyor that the Municipality hired, Carlos Vega Santos, will conduct a demarcation that will take between three and five months. He added that, until then, he will not decide on the structure.

Laureano said any use given to that property would affect the coastal resource so it should be demolished, and the cost could be defrayed with existing federal funds for that. In an interview with the CPI, the Mayor did not rule out demolishing the structure, depending on what the demarcation reveals, but said such a decision would have to be consulted with the Department of Justice due to the investment of $8.5 million in public funds that project entailed.

The VIDAS spokesman added that they are keeping an eye on recent purchases of large extensions of land on the coast of Vega Baja fearing new residential complexes will be developed and that these constructions could affect the ecosystem.

For example, in 2022, three parcels of land in the coastal area known as Sarapá were purchased by Vacation Villas Puerto Rico, LLC, and Caribbean Waterfront LLC. Mason Edward Gorda and Dennis Keith Bostick are on the registration record of both corporations, as resident agents, and administrators, respectively. Keith Bostick is another Act 22 beneficiary. Transactions related to the land totaled almost $2.4 million, according to CRIM’s digital cadaster.

Last year, real estate firm Reality Realty PSC announced on social media the sale of part of these lands as a “privileged location” because it is two miles from the Vega Baja resort, 10 from the Dorado resort, and nine from the Ritz-Carlton Reserve in Dorado.

Cruz Molina said he is unaware if there is any specific development proposal for these lands and added that they are not located in the beach area.

At least one of the three plots of land is in a Special Flood Risk Area, according to the JP.

“We’re not opposed to development, but we are against the displacement and occupation of spaces that are public domain assets, that are in the maritime terrestrial zone, inhabited by protected species and with archaeological heritage in their subsoil,” said Laureano.

The VIDAS spokesman said one of the ways to maintain balance in construction is for the OGPe to be strict in requiring the completion of an Environmental Impact Statement in coastal projects and to cease the practice of allowing categorical exclusions. The categorical exclusion is a declaration submitted by the developer certifying that the project will not have a significant environmental impact, according to the JP.

“[The abuse] in categorical exclusions gives way to continuing to build where they shouldn’t, nor can, and that is legalizing illegality,” said Laureano. “You see the collaborative efforts that have been carried out for years by nonprofit organizations, academic entities, and the scientific divisions of both local and federal agencies, but those deciding in the government agencies, who are supposed to be the regulators, they row the opposite direction of what conservation and sustainability is,” Laureano added.

In mid-November, independent Senator José Vargas Vidot filed, at the request of VIDAS, Senate Bill 1395 to establish the Submarine Gardens of Vega Baja and Manatí Natural Reserve Act. The measure would order the DRNA to develop, in collaboration with government entities and nonprofit non-governmental organizations, a management plan to manage, rehabilitate and conserve the area.

The Senator’s press officer, Sofía Rico, mentioned that they hope the bill will go to study in a commission in the next legislative session that starts in January.

The mayor of Vega Baja said he would support the designation of the nature reserve and that, even while he was a municipal legislator, he submitted legislation for that end.

Poor permits oversight

The director of the OGPe’s Environmental Compliance Division, Jaime Green Morales, said the environmental evaluation process, specifically for projects in the coastal zone and adjacent to the maritime-terrestrial zone, is “more rigorous.”

The CPI asked him if the rise in sea level due to the climate crisis is considered when identifying whether an area is flood-prone to grant a permit, and the answer is no. The official responded that the Environmental Compliance Division is based on the Recommended Base Flood Level Maps, developed by the JP and FEMA in 2018. So, it is up to the agency to adapt them to that reality.

“Based on the different studies that have been carried out on the coasts, like the one by Dr. Maritza Barreto, the government must update these databases (…) to see how that sea level has moved, and it’s predicted that in the coming years, it will continue to rise,” Green Morales said.

Although the JP’s press officer, Ivelisse Prado Ortiz, acknowledged that the JP collaborated with FEMA to draft the Recommended Base Flood Level Maps, she did not confirm to the CPI if they consider the rise in sea level when determining a flood zone and referred the question to FEMA, because it was the government entity responsible for its creation after hurricanes Irma and María in 2017. FEMA did not directly answer whether the maps consider sea level rise due to climate change. It sent a document with the data used to create the base flood elevation maps among which mention changes in the coast, but none directly related to sea level rise.

Oceanographer Aurelio Mercado warned that the Recommended Base Flood Level Maps do not take in consideration that the sea level is continually rising in the face of climate change. The agency also doesn’t update them enough to adapt to changes in seafloor depths.

“FEMA knows about all this,” he said. “FEMA is an extremely politicized agency. “Anything that increases vulnerability to flooding will be met with great opposition.”

The retired professor of the Department of Marine Sciences of the UPR’s Mayagüez Campus added that neither the JP nor the DRNA have the necessary technical personnel to evaluate maps like these, so “they have to accept what they are given.”

In a report issued in July 2023, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) revealed that OGPe issued construction permits without having the necessary environmental information and documents. This may be due to flaws in the Permit Management System, poor diligence by OGPe employees,, and lack of audits and staff in the Professional Regulation Division’s appropriate handling of the Registry of Authorized Professionals, the report stated.

The OIG noted that the JP only audited 0.02% of the construction permits granted in 2021 by the OGPe, autonomous municipalities, and authorized professionals. He warned that this ensures that deficiencies can be detected and corrected in time.

The former president of the JP, Luis García Pelatti, said the agency has not been effective in carrying out inspections to enforce the permit system because its responsibility for years was planning. It was not until the approval of Act 19 of 2017 that amended the Puerto Rico Permit Process Reform Act, that the inspections were entrusted to the JP. García Pelatti believed that this amendment was a “strategy” to reduce inspections because the JP lacked the resources to do them.

When the CPI asked, the DRNA secretary did not take a stance regarding the approval of projects in the coastal zone and near the maritime-terrestrial zone by the OGPe and the JP. Rodríguez Vega said her agency is not responsible for granting those permits and that DRNA employees, when evaluating a project, simply comment on why it should or should not be carried out, led by science.

“What we’re looking for is that these developments last a long time and that they don’t affect or increase the possibility of flooding and loss of our coasts,” the secretary said.

Luis Joel Méndez González and Vanessa Colón Almenas are members of Report for America.

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.