In September 2020, Vilma Velázquez Hernández was summoned for an expropriation lawsuit because, without her knowing, the house she lives with her husband in the Jardines de Barcelona complex was declared a public nuisance by the Municipality of Juncos.

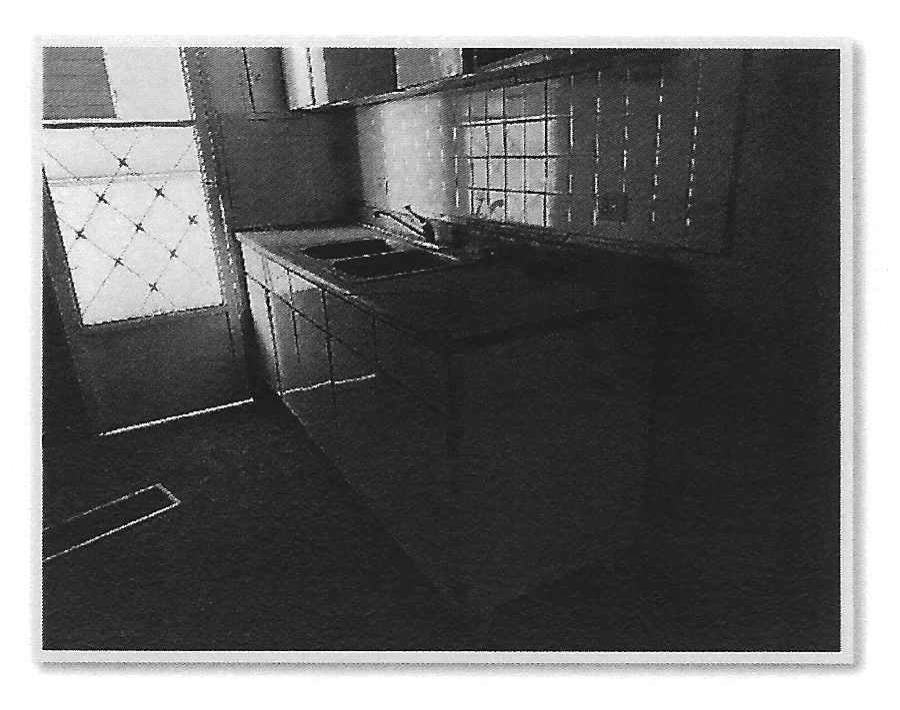

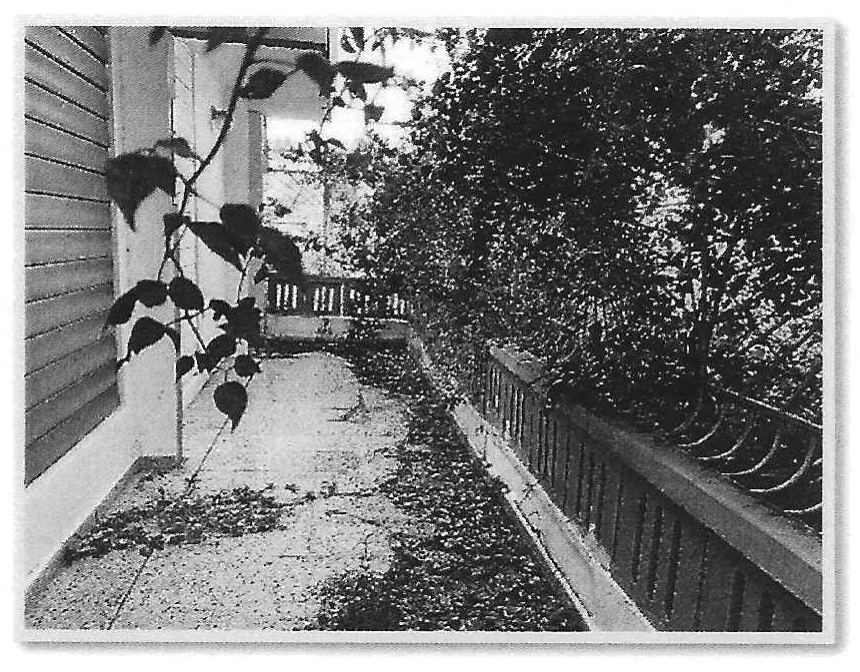

It had not been long since this retired nurse had arrived from the United States, where she stayed for four years after emigrating shortly before Hurricane Maria. The storm damaged her residence, when it blew out two windows, but after returning to the Island, and as circumstances allowed, she cleaned it, fixed it, and lived in it. So, when her summons to expropriate her home came, she couldn’t believe that she would lose the only property she had.

So, she turned to the court to file a pro se motion to prevent it. In the document she stated that her house was not a public nuisance and that it was her home.

“The pasture in the back of the house has already been cut. My house is painted now. I am going to paint the metal ornamental railings,” she wrote with her own handwriting on the paper and acknowledged that it would take a while because she did not have much money. “I paid for my property for 30 years and it isn’t fair that I lose it. I spoke with Mayor Papo Alejandro personally and he told me to forget about that piece of paper and live in it,” she added in the motion she submitted on her own behalf.

Photo of the motion presented in Court

Almost three years after Velázquez Hernández’s petition, the case to expropriate her house is still ongoing in the Superior Court (TPI, in Spanish). Her property already has a buyer: Dynamic Group LLC and JJ Inversiones, according to the compensation document presented by the Municipality of Juncos through its representative Universal Properties Realty Government Services, a company the municipal government hired to handle public nuisances and forced expropriations.

Dynamic Group has been registered since 2016 but the file does not indicate the nature of its business. Meanwhile, JJ Inversiones appears registered in the name of José A. Deyá, who is one of the executives of Universal Properties. Neither Deyá nor Universal Properties responded to the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) about the different transactions in which JJ Inversiones appears as a party with an interest in the same expropriations that Universal Properties handles. Nor did Dynamic Group establish its business relationship with Deyá, if any.

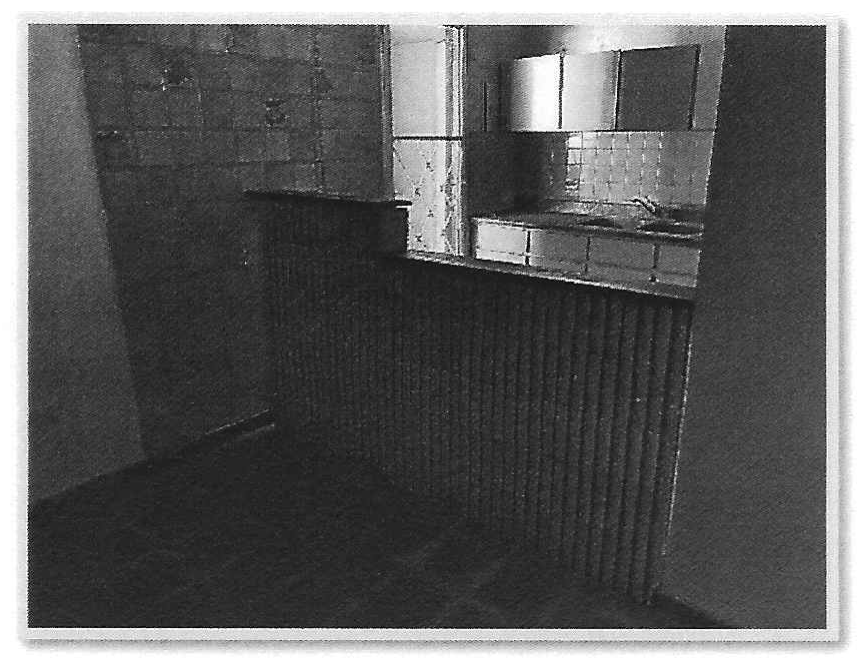

The residence in Jardines de Barcelona was appraised at $10,000, but the municipality told the court that “due to its high degree of deterioration, demolition is recommended.” Although Velázquez Hernández would lose her house, which is already mortgage-free, she would not receive any compensation after the expropriation because the $20,567 that Universal Properties billed for handling the alleged nuisance was subtracted from the $10,000. The invoice included expenses for the supposed maintenance of the house that the retired nurse and her husband cleaned little by little.

A debt of $28,558 with the Municipal Revenues Collection Center (CRIM, in Spanish) was also subtracted from the compensation, which according to the owner is not real because “this is the only house I have had all my life” except for the four years that due to personal circumstances, she was away from Puerto Rico.

Velázquez Hernández is confident — more given to her religious faith than anything else — that the case will be resolved in her favor. “My God helps me,” she told the CPI, standing in the home’s driveway. Although at the same time, she still worries about this situation because she believes “that here [in Puerto Rico you see thousands of trickery.”

If they expropriate it, “I’ll be on the street,” she said.

The CPI went to city hall to ask Mayor Alfredo “Papo” Alejandro why the Municipality moved ahead with this expropriation, according to the judicial file, but the municipal executive was not there and did not respond to an interview request that was made more than a month ago.

The goal isn’t just to eliminate the nuisance

Since the approval of the 2020 Municipal Code — which repealed the Autonomous Municipalities Act and facilitated the acquisition and disposal of public nuisances — almost half of the municipalities, 35, hired companies and law firms to handle public nuisances and their forced expropriation.

Currently these services — with different stipulations and benefits — are offered by Universal Properties Realty Government, Francis & Gueits law firm and City Renewall. The latter two only have business with the Municipality of Caguas. Nonprofit organization Centro para la Reconstrucción del Hábitat has collaborative agreements with 17 municipalities.

The attorney for Universal Properties Realty Government Services, Antonio Álvarez Torres, told the CPI in March that the municipalities that are his clients have no interest in taking properties away from anyone and that the main goal is to eliminate the public nuisance.

But the judicial record shows examples, such as that of Velázquez Hernández, in which they persist in taking away the property from its owners even when they show interest in keeping it, and even live in it. The CPI investigation indicates that the municipalities have given up on 32 expropriations but for different reasons and not exclusively because the legitimate owners have expressed their interest in eliminating the nuisance status. For this investigation, the CPI reviewed 120 cases filed with the TPI by Universal Properties and the law firm Francis & Gueits, and one filed by City Renewall.

Plenty of nuisance declarations

Beatriz Flores was buying the house that belonged to her grandfather’s estate from her relatives when she surprisingly found out that the two-story building was declared a public nuisance by the Municipality of Juncos and that her family would lose it without getting a single penny as fair compensation.

The property, which consists of two houses in the centric Villa Ana neighborhood, was appraised at $8,200. The appraiser hired by Universal Properties estimated that the structure was worth $1,388, and that it needed to be demolished. The $8,200 represented the cost of the land, after discounting the cost to demolish the structure.

Unbeknownst to the family, the house already had buyers. Initially, the companies Dynamic Group and JJ Inversiones Inc. showed interest in acquiring the property as soon as the court ordered its transfer to the municipality. Subsequently, these two companies withdrew, and Universal Properties agreed to sell the property to WCP Solutions LLC, registered in 2019, but which does not provide information as to the type of business it does in its incorporation documents.

“This was fraudulent from the start,” Flores said of the property appraisal and some $20,567.25 in maintenance, administrative and legal expenses that were billed by Universal Properties.

On February 17, 2021, Judge Migdalí Ramos Rivera issued a resolution handing over the property to the Municipality of Juncos without having the town deposit any money to compensate the Pabón family.

Fair compensation is the money that the municipal government must pay to the person who loses their property. This money is deposited with the court to prove that payment will be made. The consignment is made by the person interested in acquiring the property, be it the municipality or a buyer.

It is through this resolution that the succession found out about the proceedings against them initiated by the Municipality of Juncos and went to court. Attorney Carmen Alfonso Arroyo requested that the resolution be annulled because Flores had already initiated a process to acquire the house of which her mother was one of the heirs and pay a debt of $16,205 owed to the CRIM. By then, “they [the Municipality and Universal Properties] were already trying to register the property [in their name] in the registry,” the lawyer explained to the CPI.

“In this case, the sole purpose of the Defendant [the Municipality of Juncos] was to transfer the property to a private citizen for a ridiculous price,” Alfonso argued in her request to dismiss the eminent domain case.

The Municipality’s legal representation — paid by Universal Properties — responded that there was no problem with the petition that Alfonso filed in court if Universal Properties collected its $20,567.25.

Flores told the CPI and, as her family told the court, that they had evidence to show that “we provided the maintenance of that house” and that the notification process was allegedly defective. The family did not acknowledge Universal Properties’ debt.

Seeing that the case was proceeding in court, Alfonso sent the mayor a letter of intent to sue for damages and the court later dropped the case. “This case started wrong from the beginning. They declare a property a nuisance that is not really a public nuisance,” the lawyer argued.

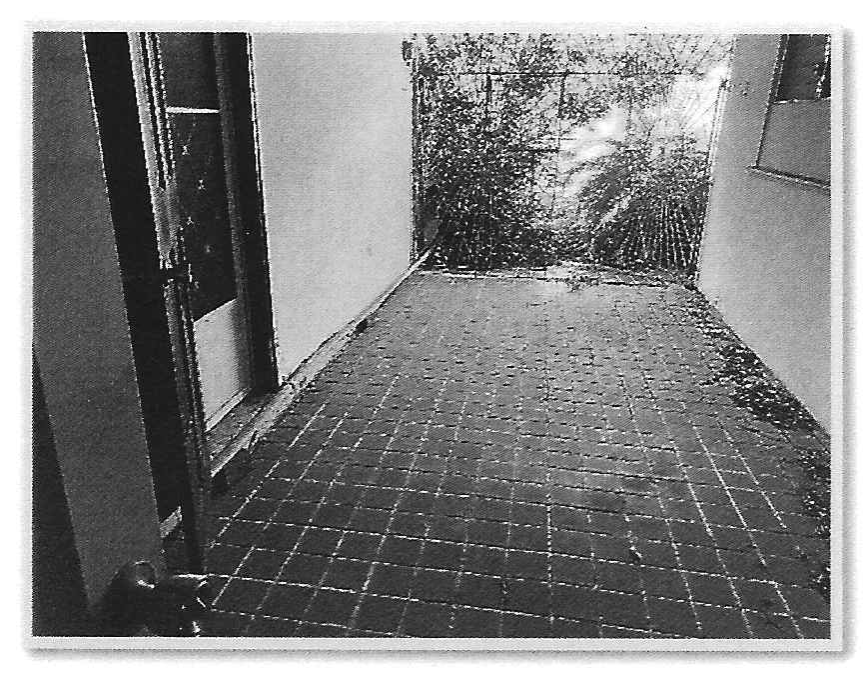

The structure that the Municipality told the court had to be demolished due to its poor condition, is currently Flores’ residence.

Demolitions that don’t happen

In 84% of the 121 eminent domain cases filed in court between 2020 and 2023, show that the properties must be demolished and the costs of that supposed demolition and cleaning of that rubble have been subtracted from the appraisal. According to the appraisal reports, this has the effect of lowering the valuation of the properties and reducing the price that the person or company that will buy the property will pay.

Court records show three properties to be expropriated in Caguas and Guayama with negative appraisals due to demolition costs. From the start, the property owner owes the buyer without even deducting the bill from the company that handles the nuisance and the debt with the CRIM.

Judge Ramos Rivera has before her consideration an eminent domain case of a residence in the Delgado neighborhood in Caguas, which has an appraisal of -$3,800. In Guayama, Judge Harry E. Rodríguez Guevara was presented with an appraisal of -$17,700 for a cement house in the town’s Vives neighborhood, and Judge Josian Rivera Torres was presented with another one of -$19,100 for a house in Bello Horizonte, in that same town.

On September 2, 2021, Ana Aida López Matos went to court in an urgent request to stop the eminent domain of a three-story building in the Juncos urban center that she co-owned. She was generating an affidavit of heirs, a process for which she had a hearing in October 2021 at the same Caguas Judicial Center.

Her plea came three weeks after Judge Annette Prats Palerm ruled in favor of the transfer of the property to the Municipality of Juncos, which already had a sales contract with José Luis Hernández García. In less than a year, the buyer had the property for which he paid $29,000 registered in his name. With the judge’s consent, López Matos lost her property without receiving a single penny of compensation.

The appraiser valued the land on which the property sits at $10,800, but recommended demolition of the building and subtracted from the value of the property the $10,272 that he estimated its demolition would cost. So, the property was appraised at $600.

A total of $20,567.25 invoiced by Universal Properties was subtracted from the value of the property owned by López Matos, who had no debt with the CRIM, so it turned out that the property ended up with a negative balance of -$19,967 and nothing was consigned to compensate the owners.

Of the $29,000 that Hernández García paid for the building, $20,567.25 was to be used to pay Universal Properties. At present, the structure — which the appraiser said should be demolished — has a post office, an entertainment room on its first floor, and the other two floors serve as apartments for rent.

Between January 2020 and May 2023, the Juncos municipal government obtained 12 final eminent domain sentences in its favor among the 22 cases it presented; it withdrew in seven processes, and there are three currently open in court.

Of the 12 expropriated properties, the CPI confirmed that the municipality sold at least four at a value between $24,000 and $29,000. The mayor did not tell the CPI, although he was asked more than a month ago how much the Municipality received from those sales after subtracting the more than $20,000 that Universal Properties retained in each transaction.

“We are taking steps to gather the requested information, which will be notified once it is completed,” according to a letter dated April 25 signed by Alejandro. The letter was sent to the CPI on May 30 after following up on the request for information. At press time, the information was not available.

The Municipality of Las Piedras declared a house in the April Gardens neighborhood a public nuisance, which, from the photos included in the appraisal report, does not seem to fit that classification. The eminent domain process was done at the request of former New Progressive Party (PNP, in Spanish) senator José Ramón Díaz Hernández, who was interested in and was able to buy the house.

The residence was appraised at $14,000 after deducting the estimated $6,216 it would cost to demolish. On December 20, 2021, Judge Marieli Rosario Figueroa issued a ruling in which she accepted the appraisal and to refrain from depositing that amount in court as compensation to the owners of the property that was not demolished. The amount of $20,567.25 billed by Universal Properties was subtracted from the $14,000, leaving the property’s value in negative. The property had no debts with the CRIM.

With Universal Properties as its go-between, the Municipality of Las Piedras sold the house to the former senator on May 19, 2022, for $25,000. Eight weeks later, Díaz Hernandez sold it for $105,000, as the CPI confirmed on the online property registry records.

Díaz Hernández explained to the CPI that he buys public nuisances and repossesses properties to remodel and sell them or keep them for himself. He said he found out the residence was on the public nuisance inventory when he passed by.

“I had to repair the house. There were some things I had to do, some investments inside the house. Repair it a lot. It’s not like I bought that and sold it the next day,” said the also mayoral candidate in Caguas.

One judge stopped them in their tracks

In total, 32 eminent domain cases have been completed in the TPI in Caguas, Guayama, Juncos, and Las Piedras, in the central-eastern side of Puerto Rico, with final orders for the cases brought by Universal Properties and Francis & Gueits and a case filed by City Renewall. In only one — of the 121 forced eminent domain cases filed in court between January 2020 and May 2023 — has the order for fair compensation been declared inadmissible.

Judge Itzel Aguilar Pérez denied that transaction because, according to what she said in the sentence, “the amounts used by the Municipality of Las Piedras to calculate fair compensation do not convince us” and demanded that Universal Properties return the $20,000 that it had charged Maritza Bonilla Castro in advanced for a property that was valued at $2,000 and that, according to the assessment presented in court, was in such poor condition that it had to be demolished.

However, Bonilla Castro did not want to demolish the cement structure, on the contrary, she wanted to make it her home.

“The property looked spectacular. It had fruit trees. The only thing I found, from what I saw on the outside, was a slightly cracked wall,” she told the CPI.

That is why it was incomprehensible to the judge that the demolition cost was subtracted from the value of the property, which had the effect of lowering the appraisal value. Furthermore, that would not be the price at which Bonilla Castro would buy the house.

“Neither the Municipality nor Doña Maritza are going to demolish the property, so it makes no sense that [$5,516 for] the cost of demolition is subtracted from the appraisal, nor that the property now appraises $2,000 with the structure when it was purchased in 1995 without the structure by the registered owners for $33,000,” Aguilar Pérez said. “They are selling the property to Doña Maritza for $20,000 when it was appraised for $2,000. Clearly, the disparity is only justified by being able to compensate for expenses incurred by Universal [Properties] that seem excessive, inaccurate, and unnecessary to us,” the judge added.

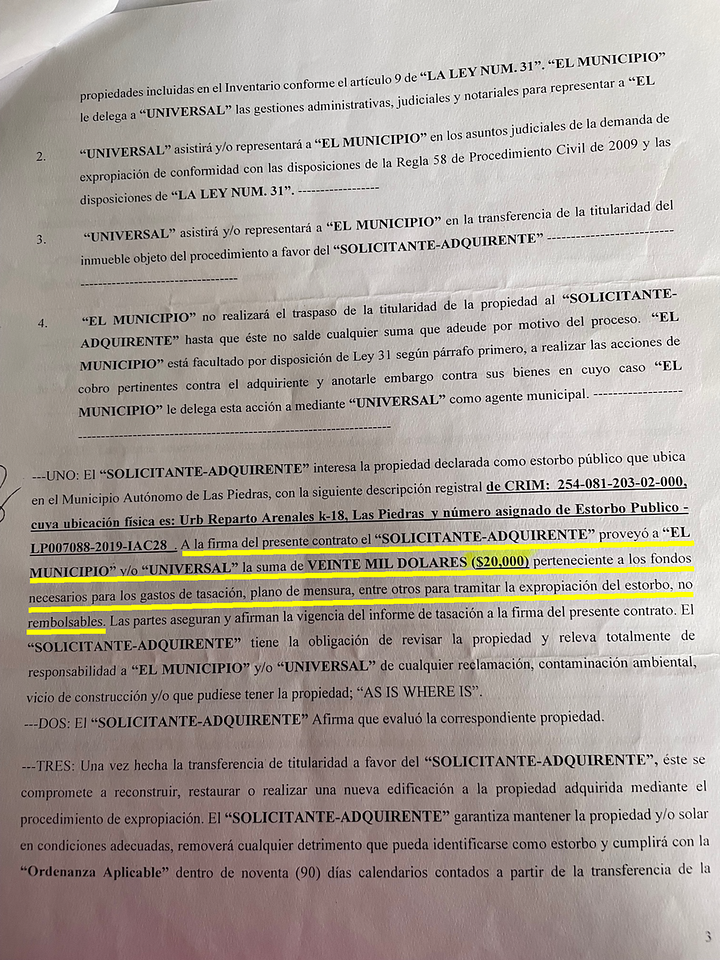

Bonilla Castro worked in Las Piedras, but does not live in that town, which is her hometown. She travels there every day to work as a caretaker. In 2020, she had hopes of owning her own home when she signed a contract with the Municipality of Las Piedras to purchase a house from the public nuisance inventory.

Hope turned into disappointment and Bonilla Castro was not only left without the home she longed for but was also on the verge of losing the only money she had saved and used to purchase the residence, $20,000 that she received when she collected a sick pay.

The contract that she signed with Universal Properties established that those $20,000 were not refundable because they would be used to cover “appraisal expenses, measurement plan, among others, to process the expropriation of the nuisance.” Bonilla Castro is grateful to the judge who ordered the property to be returned and threatened to impose penalties for each day that the turning over of the money from the failed sale was delayed.

On July 2, 2020, Bonilla Castro gave the money to Deyá González, partner of Universal Properties, who was acting as a representative of the Municipality of Las Piedras in that transaction in which she was promised that she would own a house in the Quebrada Arenas neighborhood when the Municipality completed the eminent domain. The contract that included that promise was signed by Deyá González and not by the mayor, although the agreement was done in the Municipality’s name.

Courtesy photo

“They told me that the house was going to be given to me in three months. What was not true. They promised me the moon,” she said.

In April 2019, Mayor Miguel López Rivera hired Universal Properties as the administrator of public nuisances in Las Piedras. Since then, the Municipality initiated 11 processes of forced eminent domain of real estate in different communities, according to the registry of court cases. Three homes were expropriated, and the municipal government abandoned seven processes.

López Rivera said, through his spokesperson Mei Ling Villafañe, that he does not know how many other contracts there are to buy public nuisances because Universal Properties keeps control of those contracts and not the municipal government. He also could not say how much money the municipality has made for the three sales of public nuisances.

Bonilla Castro recalls that on July 2, 2020, when he signed the contract, about a dozen other people did the same in the Las Piedras City Hall. At that time, everyone had to deliver certified checks with the money to guarantee the transaction that would culminate in the transfer of the property to their names.

“We were all happy,” Bonilla Castro recalled. “But [in the end] this left a bad taste in our mouths, tension, anxiety,” he said.

Those who buy public nuisances are not always people like Bonilla Castro who need a home to live. Of the 102 forced eminent domain cases that have come to court through these public nuisance management companies, there are 63 transactions in which the parties interested in buying the nuisances are investment companies, contractors, and real estate agents. It was not possible to find out who the interested buyers were in all cases because their names were not always disclosed during the judicial process and the mayors did not provide the CPI with a copy of the signed purchase contracts.

In San Germán, in the West, for example, the six homes to be expropriated were submitted at the request of Richport Limited Liability Company, registered in the name of Kira Golden, a beneficiary of Act 22 a law that encourages the move of individual investors to Puerto Rico, now Act 60. Richport is also listed as a possible buyer of six other properties in Juncos and Las Piedras.

With the court’s approval

By law, the court is the only entity that has the power to establish the fair compensation that the expropriated party will receive. To determine it, the judges are mainly guided by the appraisals and testimonies of the appraisers, who in these cases have been hired by Universal Properties and the Francis & Gueits law firm.

From an analysis made by the CPI, of the 121 eminent domain cases filed in the Caguas, Mayagüez, Humacao and Guayama courts, between January 2020 and May 2023, the TPI tended to validate the expropriations and to accept the low appraisals, even negative appraisals, and the high expense bills of the companies that handle the nuisances.

This has resulted in that, in the past three years, in 87.50% of expropriations with a final sentence, the legitimate property owners received $0. In 79% of the cases, not a single penny was consigned as fair compensation, but 49 cases did not have a final sentence, which means that judges can still accept or reject the compensation presented by the municipalities.

The lack of compensation to those who had their properties expropriated is the result of the low appraisals and what those who handle the nuisances charge, and the debt with the CRIM, if any. Billings for handling nuisances are always discounted from fair compensation and range from $18,737 to $32,383. Of the 121 properties that were taken to court for eminent domain, 41 had no tax debts.

Of the 121 cases filed in court by these public nuisance management companies, judges have granted 81 of the petitions. In addition to Judge Aguilar Pérez, who declared that the compensation proposed in Bonilla Castro’s forced expropriation was inadmissible, Judge Julio A. Díaz Valdés has dismissed five eminent domain claims.

Meanwhile, Judge Elías Rivera Fernández is one of the few judges who has refused to accept the appraisal that was presented to him and, for example, ordered the Municipality of Caguas, represented by the Francis & Gueits law firm, to carry out a new appraisal of a case that still active.

“The comparable [numbers] in terms of land were not worked out fairly. It must be amended with the valuation according to the same measurements that they used for the comparable properties,” according to the transcript of the judge’s comments.

According to the court document, Rivera Fernández also questioned the property maintenance expenses billed by the firm.

“Maintenance bills were submitted for properties that no one has maintained,” according to the March 20, 2023, minutes. “If they are going to demolish the property, why are they going to spend so much on maintenance? The court’s reservation was regarding the maintenance that has been invoiced and has not been provided because the photos reflect it that way,” she adds.

Likewise, there were 21 properties that were valued for just between $350 and $9,000, but Universal Properties and Francis & Gueits billed close to $20,000 for their expenses to care for and manage these devalued properties. In total, 74 properties were appraised for $20,000 or less, so the property’s debts to Universal Properties and Francis & Gueits also exceeded the appraised value.

Only three properties in Caguas had appraisals above $200,000. An almost 17,000 square-meter plot with an industrial structure on it for which the interested buyer deposited $186,554 in court; a residence in Caguas Real for which $190,642.07 was deposited as compensation; and another in Mansiones del Golf for which the owner could be compensated with $145,796.

The three cases are pending judgments at the Caguas Judicial Center. According to court records, First Bank and Luna Residential II LLC — which is the bearer of the mortgage promissory note — appeared as parties with interest in the eminent domain process of one of the residences, and Banco Popular appeared in the process of expropriation of the other residence as a mortgagee.

Luna Residential II — a domestic company registered in 2021 — did not oppose the expropriation of the four-bedroom house, with a pool and jacuzzi declared a public nuisance in Caguas Real but did oppose the appraisal and compensation of $190,642 by saying that they have a mortgage promissory note of $1.5 million. The balance of the mortgage cancellation with First Bank is for $106,091.

Meanwhile, Banco Popular challenged the public nuisance declaration, alleging that the Municipality of Caguas, represented by Francis & Gueits, did not issue the legally required notifications. The firm denied that allegation in its response to the court. The bank has a mortgage-secured note with a principal balance of $706,045 plus interest, penalties, and other fees for a total balance of $1,154,150.

The 2021 Census Community Survey estimated that in Puerto Rico there were close to 360,000 vacant houses for different reasons and not exclusively due to abandonment or deterioration.

Vanessa Colón Almenas is a corps member of Report For America.

Próximo en la serie

2 / 8

¡APOYA AL CENTRO DE PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO!

Necesitamos tu apoyo para seguir haciendo y ampliando nuestro trabajo.